I have always been intrigued by the larger-than-life poets John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, friends in real life. They saw themselves as ‘Prometheans’ bringing the Fire of Reason to humanity. They created a new style of poetry to uplift the mind and spirit. Though attacked by the British aristocratic establishment their poetry grew in popularity and gained a reputation as some of the best works in world literature.

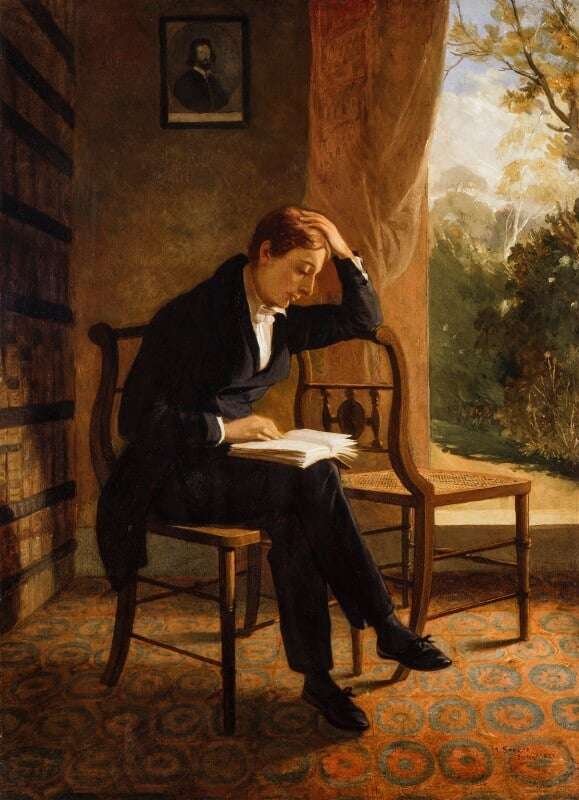

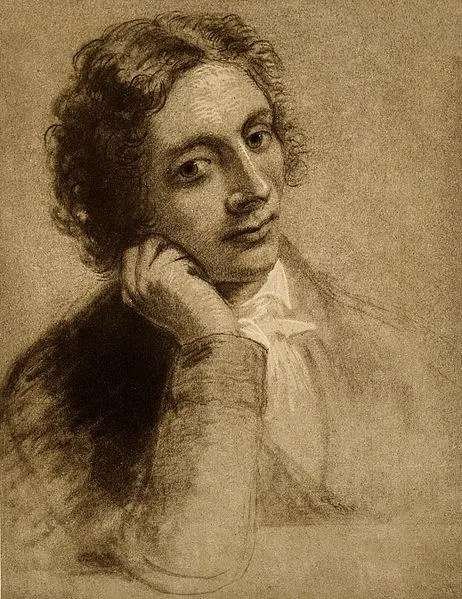

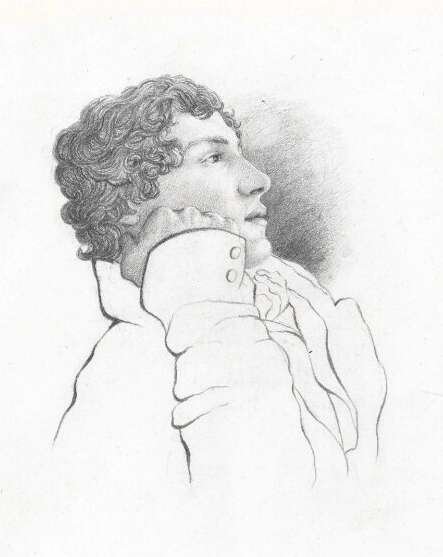

John Keats (1795-1821) is considered one of the greatest poets in history and is the most popular poet of the English language. Though he was criticized by the literary media and poets of his day, his fame and legacy outshined them all. His series of odes are considered masterpieces.

Keats was schooled in the classics and his work was influenced by the Greeks, Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe, Schiller, and others. In his early career, he studied medicine and was a licensed apothecary surgeon. He decided to be a full-time poet and produced his most prolific work between 1814 and 1820. He struggled and was never successful in his lifetime, though he did get published and sold some books. He was supported by a group of poets, writers, and critics who saw his genius. He died just as he was getting recognized and becoming successful.

Keats was engaged to marry Fanny Brawne (1800-1865) whom he met in Hampstead in 1818. Aware that he was dying, he wrote to Fanny Brawne in February 1820, “I have left no immortal work behind me – nothing to make my friends proud of my memory – but I have lov’d the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remember’d.” Keats died of tuberculosis at the age of 25 in Rome, Italy.

After his death his popularity rapidly grew in England and the U.S. His poetry was championed by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Leigh Hunt, William Hazlett, John Reynolds, Alfred Tennyson, Richard Milnes, William Rosetti, Frederic Stevens, and others.

Bright Star, a romantic film about Keats and Fanny Brawne, was released in 2009 to much critical acclaim and awards. Jane Campian directed the film. Ben Whisham played Keats and Abbie Cornish played Brawne.

Keats’ Poetry

John Keats created a new and revolutionary type of short lyrical poetry which accentuated extreme emotion and intellect through metaphor and natural imaging. Keats believed in the Platonic concept of higher universal principles that guide Nature and human Reason. His poetic objective was to evoke these higher principles in the mind and soul – to aspire to the sublime.

His method was to lead the reader away from sensuous images and to evoke higher ideas in the mind through the use of “Metaphor”. He was a follower of the Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton style of using “Blank Verse” and Metaphor in poetry.

Keats studied Dante’s musical lyrical style and his metaphorical technique. He created his own language of metaphors, ironies, and paradoxes. To Keats everyday language does not adequately communicate creative beauty. He asserted that the higher mental processes already exist within us but need to be awakened. Beauty does not come from the senses but from an unseen power of the mind and imagination.

John Keats’ Quotes on what is poetry:

“Poetry should be great and unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself, but with its subject.”

“A poem needs understanding through the senses. The point of diving in a lake is not immediately to swim to the shore but to be in the lake, to luxuriate in the sensation of water. You do not work the lake out, it is a experience beyond thought. Poetry soothes and emboldens the soul to accept a mystery.”

“Poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by singularity, it should strike the reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a remembrance.”

“With a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.”

“Heard melodies are sweet, but the unheard are sweeter.”

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

“I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections, and the truth of imagination.”

“What the imagination seizes as beauty must be truth.”

Bright Star, 1819

Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night,

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like Nature’s patient sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still steadfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

When I Have Fears, 1818

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high-piled books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love; – then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

Bright Star movie

To Sleep, 1816

O soft embalmer of the still midnight,

Shutting, with careful fingers and benign,

Our gloom-pleas’d eyes, embower’d from the light,

Enshaded in forgetfulness divine:

O soothest Sleep! if so it please thee, close

In midst of this thine hymn my willing eyes,

Or wait the “Amen,” ere thy poppy throws

Around my bed its lulling charities.

Then save me, or the passed day will shine

Upon my pillow, breeding many woes,—

Save me from curious Conscience, that still lords

Its strength for darkness, burrowing like a mole;

Turn the key deftly in the oiled wards,

And seal the hushed Casket of my Soul.

Endymion, intro

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of despondence, of the inhuman dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy days,

Of all the unhealthy and o’er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all,

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits. Such the sun, the moon,

Trees old and young, sprouting a shady boon

For simple sheep; and such are daffodils

With the green world they live in; and clear rills

That for themselves a cooling covert make

‘Gainst the hot season; the mid forest brake,

Rich with a sprinkling of fair musk-rose blooms:

And such too is the grandeur of the dooms

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

All lovely tales that we have heard or read:

An endless fountain of immortal drink,

Pouring unto us from the heaven’s brink.

John Keats House, Hampstead

Ode to a Nightingale, 1819

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy,

Though the dull brain perplexes and retards:

Already with thee! tender is the night,

And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne,

Cluster’d around by all her starry Fays;

But here there is no light,

Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown

Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

The same that oft-times hath

Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

Bright Star movie

On Seeing the Elgin Marbles, 1817

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Yet ‘tis a gentle luxury to weep,

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep,

Fresh for the opening of the morning’s eye.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

Bright Star movie

To Autumn, 1819

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, Where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Ode on Melancholy, 1919

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf’s-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss’d

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow’s mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

Keats Shelley Memorial House, Rome

References

A Defense of Poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1840.

John Keats, Walter Jackson Bate, Harvard Press, 2009.

John Keats: A Life, Steven Coote, Holder & Stoughton, London, 1995.

John Keats The Poems, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1906.

John Keats vs. The Enlightenment, Paul Gallagher, Fidelio, 1996.

Keats Great Odes and the Sublime, Daniel Leach, Fidelio, December, 2009.

On Didactic Poetry; On Epic and Dramatic Poetry, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. 1797.

On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry, Friedrich Schiller, 1795.

Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Plato (428-348 BC).

The Philosophy of Composition, Edgar Allan Poe, 1848.

The Poetic Principle, Edgar Allan Poe, 1850.