I have a love affair with haiku poetry, which I discovered while studying world literature at Wayne State University in Detroit. While in college, I became familiar with the Zen philosophy of Alan Watts, D.T. Suzuki, and the Zen koans in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. That led me to Japanese haiku poetry and then on to the American Beatnik poets.

What captured my fascination about this form of literature, is how a haiku poem can make such a profound aesthetic statement in only 17 syllables, or less. They are equivalent to a Zen koan riddle intended to evoke an “Aha!” moment. Haiku is refreshing and distinct from other poetic forms. The short format forces the poet to communicate the intended poetic concept in its essence with brevity and clarity.

I have written hundreds of haiku poems over the years, some of which are compiled in my haiku poetry book entitled Blue Harlequin. A haiku poem is seldom planned; at least for me, it comes to mind fully written. The poem is triggered by seeing a moment that causes me to stop in awe – like a butterfly landing on my sleeve; or listening to a mother on the train sing a lullaby to her baby; or seeing a young child catch a snowflake on her tongue; or watching a sunset reflected on a lake, then suddenly, swans land on the reflection.

To me, reading and writing haiku is a celebration of beauty of the present moment.

In the following pages, I have included some of my favorite haikus, both classic and modern. I hope that they help you to fall in love with the genre of literature, as I have, and prompt you to notice and appreciate the myriad beautiful moments in the cycle of life.

Some haiku from my book Blue Harlequin

The crackle of raining acorns,

hitting dried leaves,

breaks the cricket’s song

– Bruce J. Wood

The oak tree limb

emerged out of the mist,

carrying a robin’s nest

– Bruce J. Wood

Sunset over the lake—

a blue heron’s shadow

stretches to the other shore

– Bruce J. Wood

Wilderness trail,

woods and marshes,

where escaped party balloons go to die

– Bruce J. Wood

Japanese Haiku

Haiku originated as a literary form of Japanese short poetry influenced by Zen in the 17th Century. Most of the prominent haiku master poets are of the Edo Period (1603 to 1868). The four great haiku masters are Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki.

According to The Haiku Society of America, the Japanese traditional format of a Haiku poem is 17 syllables, divided into three lines of 5 syllables, 7 syllables, and 5 syllables. Haiku traditional elements are about: kigo: seasons and nature; kirgi: a shift in concept or image; gusen: beneath the surface, touches the heart; and kyo: one with the object, poets don’t impose themselves on the object.

Some examples of traditional Japanese haiku.

Downtown

the smell of things

summer moon

Boncho (1640-1714)

Sour cherry

add wings to it

red dragonfly

Kikaku (1611-1707)

To listen,

fine not to listen, fine too…

nightingale

Chiyo-ni (1703-1775)

The thief left behind

the moon

at my window

Ryokan (1758-1831)

Modern Haiku

Haiku expanded as a popular poetic form worldwide in the late 19th Century and 20th Century. The poetic form became very popular during the ‘Beatnik’ era with the spread of Zen philosophy in the 1950s and 1960s. Beat haiku poets included Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsburg, Gary Snyder, and others. Haiku was picked up by many other poets worldwide, including such poets as Ezra Pound, Richard Wright, James W. Hackett, W.H. Auden, E.E. Cummings, and others. (Source: Haiku in English, Jim Kacian).

Contemporary haiku uses different formats and subject matter. Most often, modern haiku does not follow the 5-7-5 syllable structure and is often less than 17 syllables. Instead of nature, it often uses every day human activities and situations.

Examples of Beat poet haiku:

Sunlight mixed with dust

rises behind a truck

on the dirt road

– Allen Ginsberg

White sun behind pines,

a moth flutters past

the brown wood pile

– Allen Ginsberg

The boulder in the creek never moves,

the water is always falling

together!

– Gary Snyder

Empty baseball field –

a robin,

hops along the bench

– Jack Kerouac

Haiku Technique

According to U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins and the Haiku Society of America, haiku has certain literary techniques, as follows:

Observing the Moment – Haiku is a short impressionistic poem of three lines of 17 syllables or less. It is non-rhyming, avoids metaphor and simile, uses little punctuation, has no superfluous words, nor explanation. Haiku offers a ‘snapshot’, an observation, of a particular moment, presented as it is.

Coming from the woods

a bull has a lilac sprig

dangling from a horn

– Richard Wright

A lizard inching

with the shadow of the stone

nearer the cave’s mouth

– Elizabeth Searle Lamb

On the first day of spring,

snow falling

from one bough to another

– Virginia Brady Young

Footprints

of morning dew

lead back from the garden

– Bruce J. Wood

A summer wind –

shadow of the windmill blades

flow over the grass

– Lorraine Ellis Harr

Mood – Haiku poetry represents a poetic mood and experience of a particular moment that is put into short verse. It captures a situation that can be either ironic, poignant, aesthetic, sad, humorous, absurd, bizarre, inspirational, or spiritual.

Even the iris bends

when a butterfly

lights upon it

– Amy Lowell

Everyone on the train

listened to the mother

singing a lullaby to her baby

– Bruce J. Wood

Love between us is

speech and breath, loving you

a long river running

– Sonia Sanchez

Brevity – Haiku must paint a vivid picture while pairing it down to only the essentials; therefore, every word and syllable count. In a few words, haiku captures an image in the immediate ‘here and now’. The simplicity and brevity provide a profound statement.

Period

one blue egg all summer

now gone

– Joyce Clement

The apparition

of the faces in the crowd,

petals on a wet, black bough

– Ezra Pound

Melting snow

reveals a face

carved on a pumpkin

– Bruce J. Wood

Fun – Hai means ‘insightful’ and ku means ‘fun’. Finding meaning in the ‘joke’ is part of the joy of haiku. Despite the components of its form, haiku is not rigid and formal; it is fluid and flexible.

Insects on a bough

floating down river

still singing

– Issa

Young boys used

Nativity scene characters

to play battle games

– Bruce J. Wood

In the boulevard median

geese honk

at passing cars

– Bruce J. Wood

Morning coffee.

I watch a groundhog

eat the neighbor’s flowers

– Bruce J. Wood

Shift and Juxtaposition – The goal of a haiku poem is to evoke an ‘Aha!’ moment in the reader – the ‘eye-opening’ moment of insight – a sudden shift, twist, or surprise, or new way of seeing.

The ‘cut’ in the haiku indicates a pause that splits the poem into two sections. The ‘shift’ comes from a change from the poem’s original image, to a contrasting image. The relative disparity between the two images poses an ironic or paradoxical perception in the mind, intended to prompt the reader to reflect on the new relationship. The haiku method uses contrasting imagery, such as: macro/micro, nature/man, light/shadow, winter/wind, moon/cold, storm/quiet, etc.

The calm

cool face of the river

asked me for a kiss

– Langston Hughes

Last night it rained,

now, in the desolate dawn,

crying of blue jays

– Amy Lowell

Twigs used for

snowman arms, hug the

same spot all summer long

– Bruce J. Wood

Fallen horse –

flies hovering

in the vulture’s shadow

– Geraldine Clinton Little

All night, this headland

lunges into the rumpling

capework of the wind

– Richard Wilbur

In many of the above haiku, identifying the haiku technique is rather simple. In others, it is more subtle and may require reflection. That is the point. Aha!

Zen Koans

Essential to Japanese haiku is the tradition of Zen koans, short stories which are parables, paradoxes, and riddles. The stories are designed to confuse the listener out of everyday thinking. They ask unanswerable questions – which is the point; there are no right answers. A koan, like haiku, attempts to capture the Zen mind at the moment of ‘Enlightenment’.

Some of my favorite examples of Zen koans are from Zen Flesh, Zen Bones:

-

- The whole moon and the entire sky are reflected in one drop of dew on the grass. Dogen.

- A monk asked Zhaozhou, “What is the meaning of the teacher’s coming from the west.” Zhaozhou: “The cypress tree in front of the hall.”

-

- The most important thing is to find out what is the most important thing. Suzuki.

- The monkey is reaching for the moon in the water. Hakuin

- Before Enlightenment: chop wood, carry water.

After Enlightenment: chop wood, carry water. Zen saying - First student: The flag moves.

Second student: The wind moves

Zen master: It is your mind that moves. - Student: What is the Way?

Master Haryo: An opened-eyed man falling into the well. - When two thieves meet they need no introduction, they recognize each other without question. Mu-mon

- The cook accidentally cut off the head of a snake, mixed in with the salad greens

Master: “What is this?”, holding up the snake head found in his salad.

Cook: “Oh thank you master,” taking the morsel and eating it quickly.

Similar examples of koan-like riddles can be found in Proverbs, Books of John and Matthew, and in the Western writings of Plato, Aesop, Dante, Erasmus, Rabelais, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Benjamin Franklin, Emily Dickinson, Mark Twain, Lewis Carroll, Robert Frost, and others. For example:

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou

hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell

whence it cometh, and whither it goeth.

– John 3: 8

If you don’t know where you are going, any road can take you there.

– Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

I hide myself within my flower,

That, fading from your vase,

You, unsuspecting, feel for me

Almost a loneliness.

– Emily Dickinson

I know that I know nothing.

– Plato

The hardest thing is to understand the question, after that finding the answer is quite simple.

– Albert Einstein

Things are curiouser and curiouser.

– Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

The great thinkers and artists of all time embraced what the great master Leonardo da Vinci called Sfumato, translated as “turned to mist” or “going up in smoke”. To Leonardo, mastering Sfumato meant cultivating a willingness to embrace Ambiguity, Paradox, and Uncertainty.

Traditional Haiku Poems

The following is a sampling of haiku from the four classic masters – Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki. Selections are from The Essential Haiku and An Introduction to Haiku.

Matsuo Basho, 1644 – 1694 “The ascetic and seeker.”

Basho is revered as a saint of poetry in Japan and is deified in the Shinto religion. He was of samurai descent and was a student of Zen meditation. He reinvented haiku into a lyric form and infused his works with his original impressionistic style.

The sea darkening –

the wild duck’s call

is faintly white

Winter solitude –

in a world of one color,

the sound of wind

Summer grass –

all that’s left

of warrior’s dreams

The winter storm

hid in the bamboo grove

and quieted away

The winter sun —

on the horse’s back,

my frozen shadow

Lightening –

and in the dark,

the screech of a night heron

Coolness of the melons

flecked with mud

in the morning dew

As far as I’m concerned, Basho is the best haiku poet. He captures the most profound beauty in just a few elegant words.

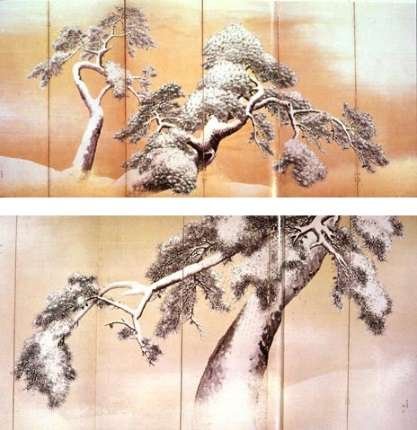

Yosa Buson, 1716 – 1783 “The artist.”

Buson was a Japanese poet and painter of the Edo Period. He combined painting and haiku to “paint an image”.

Before the chrysanthemum –

the scissors

hesitate a moment

Coolness –

the sound of the bell

as it leaves the bell

Coming back –

so many pathways

through the spring grass

A field of mustard,

no whale in sight,

the sea darkening

Butterfly

sleeping

on the temple bell

Night deepens,

sleep in the villages,

the sound of fallen water

It cried three times,

the deer,

then silence

Like Basho, Buson’s haiku leaves me in total awe of his ability to grasp the sublime.

Kobayashi Issa, 1763 – 1828 “The humanist.”

A Japanese poet, artist, and Zen priest of the Edo Period, Issa made haiku poetry more accessible to a wider audience. His poems are often tender, but many are irreverent with wry humor and satire.

In the cherry blossom’s shade,

there is no such thing

as a stranger

Crescent moon –

bent to the shape

of the cold

The snow is melting

and the village is flooded

with children

Not knowing

it’s a tub they’re in

the fish cooling at the gate

Climb Mount Fuji,

Oh snail,

but slowly, slowly

Under my house,

an inch worm

measuring the joists

Issa is like a trickster god who makes us laugh at the world and ourselves.

Masaoka Shiki 1867 – 1902 “The Reformer

Shiki was a Japanese writer and poet of the Meiji Period (1868 to 1912) who modernized haiku poetry to be more compatible to Western culture. Being an agnostic, he separated haiku from the influence of Buddhism. He rejected traditional puns and fantasies in favor of a realistic observation of nature.

Toward those short trees we saw a hawk descending on a day in spring

Green in the field was pounded into rice cake

Looking down I see, cool in the moonlight, 4,000 houses

I wonder a cow has eaten up the leaves, a spider lily

A dog howling, sound of footsteps, longer night

Shiki cuts straight to the point, no frills, just essence.

Japanese Death Poems

Many haiku poems have been written by Zen monks and Samurai warriors, while meditating on their death bed, to summarize their life in a concise, spiritual, and poetic statement – like fallen plum blossoms blown away by the wind. (source: Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, ed. Yoel Compiler)

Sick on a journey,

my dreams wander

the withered fields

– Basho

Winter warbler –

long ago in Wang Wei’s

hedge also

– Buson

A bath when you’re born

a bath when you die,

how stupid

– Issa

Bitter winds of winter

But later, river yellow,

Open up your buds

– Karai Senryu (1718-1790), Edo period poet

Death poems

Are mere delusion –

Death is death

– Toku (1710-1795) a Zen monk

Death poems are unique to East Asian culture. They see death as a part of life and view it as a natural order. Instead of being afraid of death or full of despair at the end of one’s life, a death poem is written as a reflection and celebration of life. The purpose is not to mourn death but to awaken the joy of life.

In Conclusion

Haiku has taught me to be patient and to reflect on the experience of the world around me at that exact place and time. As a poet, writer, and artist, I have always tried to grasp Beauty and the Sublime. My working with the haiku method has enriched my art and has had a profound impact on my life. I never know what the next moment will bring, but if I look, I will find the Aha! haiku moment right in front of me.

Every day, I see haiku moments by watching birds and animals, seeing children at play, walking in the woods, or while driving, dining, shopping, or sitting in the park.

Once, in late October, when backpacking on the Jordan River Trail in northern Michigan, I trekked through woods, hills, and fields, and wrote down haikus that came to mind.

The hawk freezes,

perched on the fence railing,

then darts off in an instant

In the open field,

the geese heads bob up and down

among the Queen Anne’s lace

Dusk lingers,

fireflies vanish in the mist

along the river banks

Woodpecker cadence echoes

through the tall pines,

among a sea of ferns

Small wooden bridge over a creek,

left a coin for the troll,

just in case

Haiku celebrates the beauty of the present moment, and as such, I find the form inherently inspirational. A profound noticing occurs in both the reader and writer of haiku. It’s amazing that such diversity and aliveness can be captured in a mere 17 syllables.

I hope you enjoyed our journey through the wonderful world of haiku poetry. Whether you are a long time lover of haiku poetry or new to the form, you can easily master haiku by enjoying the full experience of the moment. Beauty is everywhere, all you need to do is look. Aha!

Further Reading

Aware: a Haiku Primer, Betty Drovniak, Portal Publications, 1982.

The Book of Equanimity, by Hongshi Zhengljue (1091-1157)

The Blue Cliff, by Yuanwu Keqin (1063-1135)

The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson, & Issa, ed. Robert Hass, Philip Rowland, Allan Burns, Harper Collins, NY, 1994.

The Gateless Gate, by Wumen (1183-1260)

Haiku in English, Jim Kacian, W.W. Norton & Co., NY, Introduction by Billy Collins, 2013.

The Haiku Handbook, William J. Higginson, McGraw Hill, NY, 1985.

A Haiku Path, Haiku Society of America, 1994.

Haiku Techniques, Jane Reichold, Haiku Society of America, 2000.

An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems and Ports from Basho to Shiki, Harold G. Henderson, Doubleday, NY, 1958.

Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, ed. Yoel Compiler, Tuttle, 1985.

Treasury of the True Dhama Eye, by Eithei Dugan (1200-1253)

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki, Tuttle, Boston, 1957.