Several years ago I was introduced to Sylvia Plath when I came across her poem “Elm.” Included in her most popular collection, Ariel, “Elm” is a poem that skillfully personifies the emotions of despair and longing. The “dark things” that sleep in Sylvia are soft and feathery. Her cry of longing becomes a warped bird, flapping and searching in the night. This poem, like many others Sylvia has written, has an eerie kind of beauty. It is easy to become enraptured by her words, and even easier to become enraptured by Sylvia herself, and the drama and tragedy of her life. Even fifty-eight years after her death she continues to cast a shadow over American poetry and culture. Her reputation is muddled; was she an artistic genius, or unhinged and vengeful? Was she perpetually in anguish or was she self-confident and proud? The countless biographies, articles, and film scripts written about her continue to muddy the waters. Will we ever know the truth about Sylvia Plath?

“A Squeal Of Brakes. Or Is It A Birth Cry?”

If we are to believe what was written in The Bell Jar, Sylvia had several idyllic years at the beginning of her life before depression began to cast a shadow on her conscience. However, it seems as though even her gleaming childhood years had flaws. Sylvia loved her mother, Aurelia, and described her as “abnormally altruistic” and selfless (Tresca). Despite this, their relationship was not a simple one, and in Sylvia’s novel, the mother figure continually misunderstands her daughter and feels ashamed of her daughter’s mental illness. It appears the two may have appreciated each other, but had different values and communication issues, leading to a complicated relationship. Sylvia also had a tumultuous relationship with her father, Otto. In the poem Daddy, she seems to both admire and despise him at once, comparing him to God in one line and a swastika in another. Otto died when Sylvia was young, and the family lived in poverty for many years afterwards, surviving off of Aurelia’s teaching salary. Although her life was already tainted with tragedy, Sylvia was always an exceptional student and writer, publishing her first short story in Mademoiselle while she was in college. After her publication, she got a summer job as guest managing editor of a magazine, which is where her mental health began its first serious decline.

“Sitting Under The Same Glass Bell Jar”

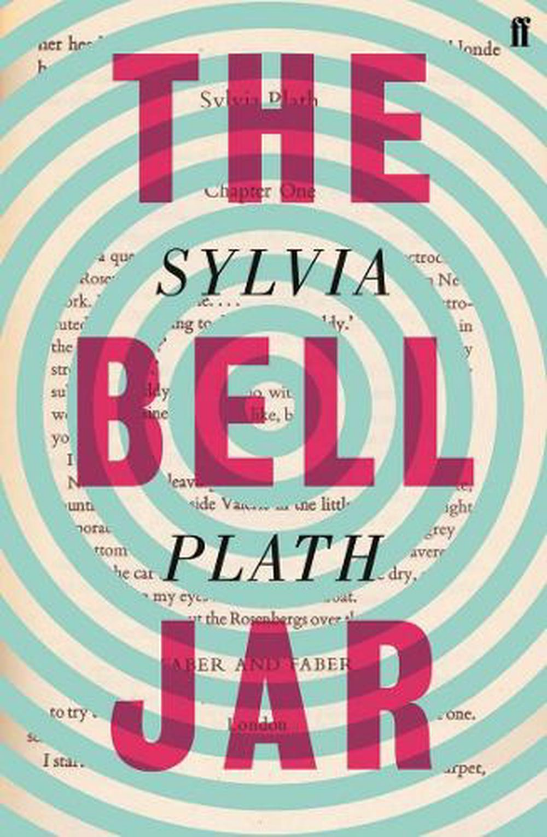

Although she didn’t write The Bell Jar until the very end of her life, the novel documents Sylvia’s first major depressive episode back when she was attending Smith College. In the book, Sylvia shares her experiences freely through the character of Esther, a young college girl who is working as the editor of a magazine. We are introduced to Sylvia’s morbidity on the very first page, with her thoughts on execution and electrocution. At the same time, we are introduced to her beautiful, descriptive writing style, which is in contrast to the dark content of her work. The character of Esther is fortunate and talented; she has come into some money since getting her magazine job and scholarship, and she has straight A’s in school. The character also immediately appears mentally unwell: “I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.” (3). As the first few chapters slowly progress, the reader gets a glimpse into the combined genius and madness of Sylvia’s personality. I found myself thrilled by her honesty about herself. Most people would try to portray themselves in a positive light if they were to write a novel about themselves, but Sylvia does not waste time on self-aggrandizement. She reveals herself as incredibly judgemental, especially of men. She bemoans the double standards present in society at the time, upset at how men could cheat and it would be overlooked unless they were engaged or married. She longed for love but dreaded the dreariness of housewife life, feeling as though she would have to give up large parts of herself in order to have children. In chapter 10, after the character of Esther leaves her

flashy new job in New York, she learns she was not accepted into a summer writing course and spirals into depression. Sylvia does not spare us from the horrific details of the illness, going into detail about sleep deprivation, loss of time, isolation, and periods of delusion. As Sylvia writes about her experience, the flaws of the mental health care system in the 1950s become clear.

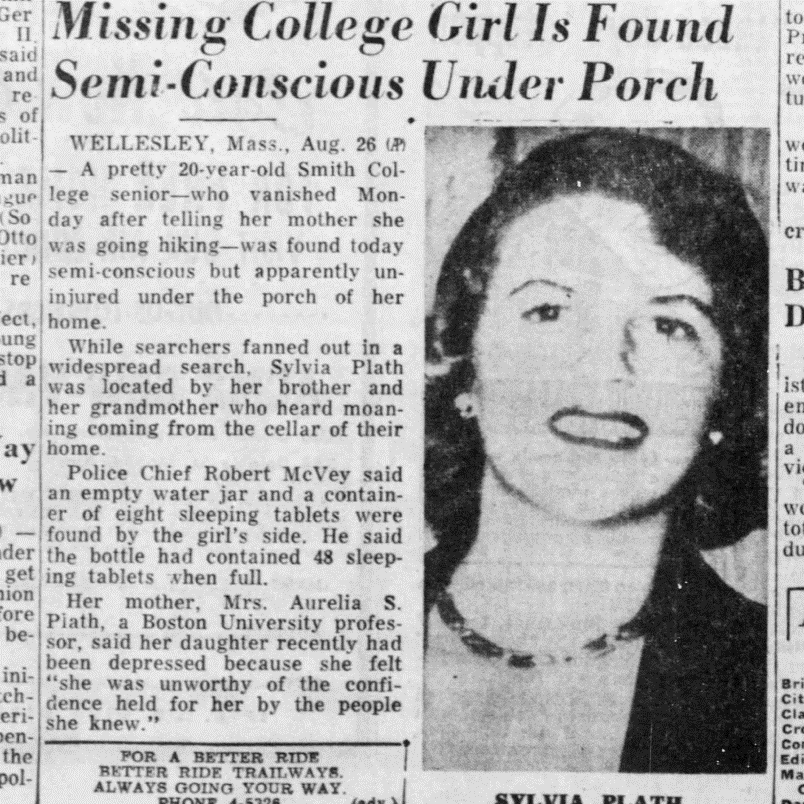

The first problem I noticed was that Esther, a woman old enough to be in college, did not know about mental illnesses. The lack of early education on these problems was dangerous to her and to others living in that time period. Esther’s first therapist was completely unhelpful, asking her how she felt without trying any of the treatments available today, such as CBT. Instead of keeping things simple, Esther is quickly given shock therapy, which harms and traumatizes her. She later attempts to commit suicide with sleeping pills, the same method Sylvia used in her attempt in 1953. After she is found alive, Esther is hospitalized, and does not improve much at all until she is brought to a halfway decent institution that treats her like a person. Esther fears asylums, saying that “the more hopeless you were, the further away they hid you.” (160). Her fear shows how substandard mental health hospitals tended to be at the time, especially large, underfunded ones.

Throughout Esther’s time at the hospital, we can see how stigmatized mental illness was among the general population. Esther’s mother, for example, is convinced that she can “decide to be alright again.” (146). A Christian woman who visits Esther seems to believe that Esther’s illness is not real, but merely a “mist” that she can stop believing in at any time. Esther herself describes her illness as being trapped in a bell jar, breathing in her own air (185). I cannot imagine going through the mental torment she went through, all while being misunderstood by not only the general public, but doctors as well.

“The Engine That Killed Her”

Although The Bell Jar contains some fictional elements, it accurately illustrates the state of mental health care in the 1950’s. Perhaps one of the greatest tragedies in Sylvia’s life was that she was failed again and again by ill-equipped doctors and the medical system as a whole. If she had been born in later decades, it is possible she might not have committed suicide. Here are a few of the controversial therapies that Sylvia either experienced or would have been aware of during her lifetime:

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Sylvia writes extensively about her fear of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in her novel. Although it is considered a safe and effective treatment for depression today, it was a more risky procedure in the 50s, as it had only been recently developed. It could cause intense pain if done improperly, and was often used as a threat to control unruly patients in mental hospitals (Sadowsky). However, it is important to mention that ECT, despite its risks, did work quite often in the treatment of depression, if it was done correctly. Sylvia also writes of more positive experiences with ECT in her novel, although in her real life she could only tolerate a few sessions of this type of therapy before succumbing to her fear of it and refusing any more (Clark).

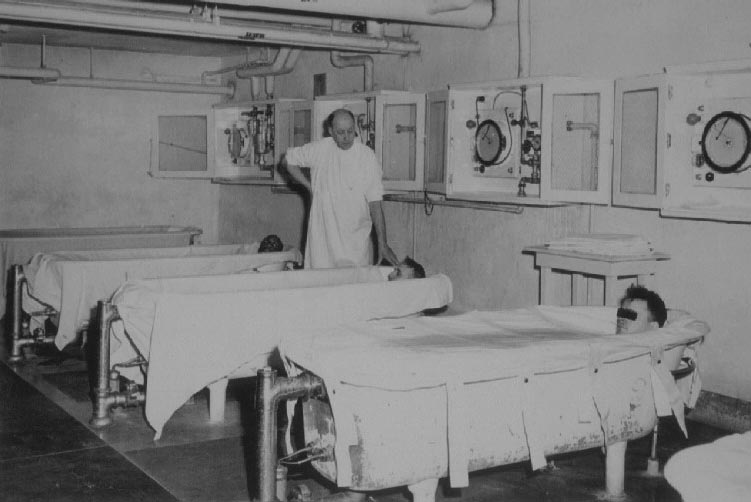

Hydrotherapy & Lobotomy

Other strange treatments used during the 50s included hydrotherapy and lobotomy. Hydrotherapy ranged from leaving patients in a bathtub for hours, to wrapping them in a cold, wet sheet (Clark, 291). The treatment was fairly useless at best, and cruel at worst. Sylvia describes meeting a lobotomy patient in The Bell Jar; a girl with scars on her head. The girl Sylvia mentions did not seem terribly harmed by her lobotomy, but lobotomies were an ineffective and incredibly dangerous procedure that could cause apathy, poor concentration, and even death (Britannica).

Insulin and Antidepressants

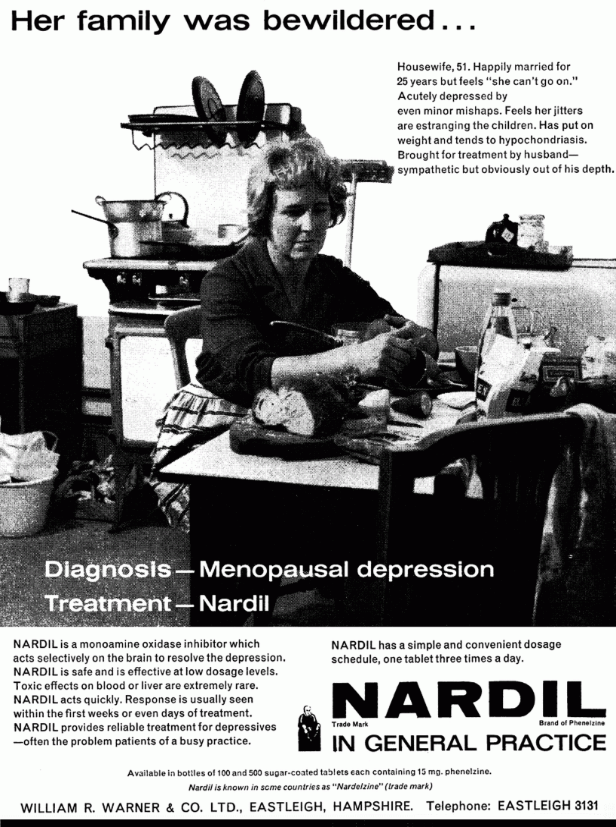

In addition to ECT, Sylvia also experienced insulin injections as a form of therapy during her first depressive episode. This was yet another ineffective and dangerous treatment. Sylvia apparently entered a “stupor” because of insulin injections (Clark, 291). Another problem that Sylvia would’ve contended with was the overprescription of psychopharmaceuticals in the 50s and 60s. Today antidepressants and other mental health medications are often prescribed after talk therapy and/or CBT therapy has been attempted, but in earlier decades they were given out much more freely. Tranquilizers such as meprobamate, reserpine, and equanil became available and were prescribed too often, causing dependency (Metzl). Housewives and mothers were especially affected by the overprescription of these drugs, and Sylvia, being a mother, would have been a target. Overprescription of drugs, and interactions of drugs, could have actually contributed to her death. At the time of her suicide, Sylvia was on two strong antidepressants, as well as codeine for respiratory illness, a sleeping pill, and another medication for fevers. The interactions of the drugs could have made her already declining mental health worse, ultimately leading to her death (Clark, 879).

“The Art Was Not To Fall”

Unfortunately, substandard mental health treatments were not the only difficulties Sylvia faced in her lifetime. After graduating college, starting her career, and getting married, the poet faced another series of problems. At the time that she wrote Ariel specifically, she was in an arduous transitional phase in her life. She had separated from her husband, Ted Hughes, who was having an affair with another woman. Divorce was somewhat scandalous in the 1960s, and Sylvia felt “damned” for being a divorcee (Clark, 765). Her depression was worsening, and only a few months before she began writing the bulk of Ariel, she had once again attempted to take her life by getting into a car crash. Out of these difficult circumstances, one of the most acclaimed poetry collections of the past century was created.

Themes

Sylvia was not a superficial poet or person; she had several themes she explored in depth, all of which helped build her reputation and legacy as a great writer. Among these themes were:

Death & Violence

One of the most obvious elements of Sylvia’s most famous work is the continuous graphic imagery used throughout. There is scalping and removal of thumbs in “Cut,” she mentions being drugged and raped in “The Jailor,” and is killed by constriction in “The Rabbit Catcher.” There are amputations, corpses, acid baths, and shrieking. Even “Letter to November,” a poem I thought seemed relatively positive, mentioned dead bodies and “death-soup.” Although Sylvia’s poetry is disturbing to read at times, I still found it beautiful even at the darkest parts. She has a way of describing grotesque things as if they belong in a museum.

Ethereal & Realistic Elements

Sylvia combines ethereal, surreal imagery with realism effortlessly. She will write about the moon, the air, and the sea, and then will mention an everyday object like the candy in someone’s purse, or a lampshade, or a vase. “The Other” mentions moon-glow, but also knitting. “Berck-Plage” describes the sea and green hills, but also “electrifyingly-colored sherberts.” If Sylvia were a less skilled poet, perhaps these everyday activities and objects would clash with the broad, ethereal way she writes about nature, but somehow she manages to put both together spectacularly.

Feminist Undertones & Anger Towards Marriage

Sylvia’s anger towards her husband for his affair as well as her complicated feelings about raising children and other “housewife” duties are apparent in her poetry. In “Lesbos” she writes about husbands calling their wives a “ball and chain,” and seems to view mothers/housewives as suffocated: “I see your cute decor/close on you like the fist of a baby.” In “The Applicant,” she feels that a housewife is “a living doll, everywhere you look./It can sew, it can cook…” This poem as a whole criticizes marriage and how quickly people will get married simply because it is a societal norm. In addition to her uncertainty about marriage, Sylvia hints at her complicated feelings on motherhood. She has a few loving poems about her children, such as “Morning Song” and “Nick and the Candlestick,” but in other poems she writes of babies as perpetually screaming, ugly, and neglected. In the line I already quoted from “Lesbos,” a baby’s fist closes around the mother in a suffocating way. Sylvia’s strong opinions on these topics make her writing piercing and real.

Personal Power & Identity

We think of depression as a disorder that gives a person low self-esteem and an identity crisis, but neither of these traits are overly present in Sylvia’s writing despite her depressed state. In fact, the opposite is the case in poems such as “Lady Lazarus,” “Ariel,” and “Stings.” The writer comes off as confident and aware of who she is (a powerful woman). In “Lady Lazarus,” she is a woman with red hair who “eats men like air.” In “Ariel” she is “the arrow,/the dew that flies/suicidal, at one with the drive/into the red/eye, the cauldron of morning.” In “Stings” she is “flying/more terrible than she ever was, red/scar in the sky, red comet/over the engine that killed her.” There is something triumphant in all of these lines, and although her mental illness eventually brought her enough unhappiness to end her life, Sylvia was clearly not self-effacing and knew her worth.

Sylvia’s Most Famous Poems

Although nearly all of Sylvia’s work is admired today, the poems described below have stood the test of time especially well. Their subjects range from power and freedom to the concepts of life and death, and they are what helped Sylvia rise to her current level of fame.

Lady Lazarus

This poem serves as a great introduction to Sylvia’s work: in it she speaks of death, rebirth, and personal power, topics that she revisits again and again. “The speaker is a woman who has the great and terrible gift of being reborn,” Sylvia says in an introduction to this poem. Emphasis should be on the word “terrible.” The speaker’s flesh is eaten by “the grave cave,” and she has died three times before the death described in the poem (14). Sylvia mentions her first suicide attempt in the thirteenth stanza, and goes on to suggest that dying is her vocation, something she does “exceptionally well.” (15). The poem is about personal moments (suicide attempts and rebirth), yet Sylvia speaks about being watched and scrutinized through all the horror. Both “the peanut-crunching crowd” and her enemy observe her and even pay to speak to or touch her in her worst moments. Death, which should be a private thing, becomes public for Sylvia. In this way, “Lady Lazarus” almost seems like a prophecy. Sylvia’s death was scrutinized and replayed in people’s minds decades after it happened, in the same way the speaker’s death in “Lady Lazarus” is watched and enjoyed. However, Sylvia reminds us that, in the end, she will not be brought down by her enemies or her rabid audience: “Herr God, Herr Lucifer/Beware/Beware” she warns us (17).

Best Quote: “Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/and I eat men like air.”

Ariel

As the poem after which her final collection was named, “Ariel” has been the recipient of boundless praise. The piece is thought to be about a wild ride Sylvia had on her horse, Ariel. However, Sylvia also weaves the essence of Ariel, the wind spirit from The Tempest, into the poem. Unlike many of her other works, “Ariel” feels vague, and serves to fill the reader with emotion rather than tell a complete story. Sylvia presents herself as “god’s lioness,” being hauled through the air and transformed from “foam to wheat, a glitter of seas.” (33). She melts and pivots like a dancer, experiencing freedom and power. Towards the end of the poem she describes herself as an arrow flying towards the rising sun. This may relate to a quote from her novel, The Bell Jar, in which the character of Willard says: “What a man is is an arrow into the future, and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from.” (Plath). Sylvia obviously disagreed with this sentiment, and she reverses the quote in “Ariel,” making herself the arrow into the future. The poem encapsulates her wild nature, her wish to be free, and her confidence and drive. It is easy to see why this poem is so renowned.

Best Quote: “And I/am the arrow,/the dew that flies/suicidal, at one with the drive/into the red/eye, the cauldron of morning.”

Daddy

Out of all of Sylvia’s difficult, dark poems, “Daddy” is perhaps one of the most disturbing. The piece details Sylvia’s suffocating relationship with her father and her wish to be free of him. Sylvia starts by describing herself as a foot stuck in a shoe, “barely daring to breathe” because of her father’s terrifying and unrelenting presence. She goes on to reveal that, as a child, she saw her father as larger-than-life and god-like, comparing him to a “ghastly statue” rising from the Atlantic ocean. As the poem continues, her father becomes more and more sinister, being compared to a Nazi, and then a swastika, “so black no sky could squeak through.” By the thirteenth stanza, Sylvia turns her scathing eye from her father to her husband, who she describes as a model of her father’s cruelty and a vampire. In the last few stanzas, she kills both husband and father, and describes villagers dancing on her father’s grave. Perhaps what makes “Daddy” so memorable is that the blood and death mentioned throughout the poem contrast starkly with the childlike rhymes and words Sylvia uses. Murder and torture described in the simple voice of a five-year-old is enough to give any reader the chills. Still, the poem manages to have a triumphant, although brutal end: Sylvia is free.

Best Quote: “Daddy, I have had to kill you./You died before I had time–/marble-heavy, a bag full of God.”

Tulips

“Tulips” is one of Sylvia’s most beloved poems, and describes her views on life and death. The poem contrasts a sterile white hospital room with a loud and vivacious bouquet of tulips on Sylvia’s bedside. The white room represents death, and Sylvia is comfortable in it, feeling at peace as she is stripped of her sense of self, her baggage, and her relationships. “I am a nun now,” Sylvia says. “I have never been so pure.” The tulips, in contrast with the bare and sterile room, represent life. Sylvia didn’t ask for the flowers, and finds them painful to deal with. The tulips breathe and speak and hang heavily around Sylvia’s neck like “a dozen red lead sinkers.” She wishes they were locked away but seems powerless to get rid of them. At the end of the poem, her heart betrays her by continuing to beat, and it seems she is coming back to life somewhat against her will. Most analyses of the poem agree that Sylvia chooses life over death, despite the difficulties of living. However, despite the hopeful ending of the poem, there remains a sense of powerlessness and entrapment in the lines. It may be that, just as she wished for freedom from her parents, husband, and mental illness in other works, Sylvia wrote “Tulips” to express her desire to be free from life itself.

Best Quote: “And I am aware of my heart: it opens and closes/its bowl of red blooms out of sheer love of me.”

My Personal Favorites

Now that I’ve explored the popular opinion, here are the poems that stood out to me, personally, while reading Ariel. Sylvia’s descriptions of the natural world combined with her explorations of depression and identity really captured my attention.

Elm

I mentioned before that “Elm” speaks to me. I have a personal attachment to it because I feel it captures the desperate longing to be loved in a way I have never seen before. It also touches on fearing one’s own dark and unacceptable emotions, which I love and find relatable. The elm tree in this poem is apparently based on a real tree which grew by Sylvia’s house in Devon, England. As the poem starts, the elm speaks, telling us that she knows “the bottom” and does not fear it. She has “suffered the atrocity of sunsets,” as well as violent winds and the harsh scrutiny of moonlight (27-28). The elm, which is said to represent a suffering woman, experiences anguish, vulnerability, and loss. She is “inhabited by a cry./Nightly it flaps out/looking, with its hooks, for something to love.” (28). In the end, the elm, or the woman, feels as though her will is paralyzed by her longing for love and her difficult emotions and faults, and believes that she will die. This poem made me feel seen, and helped me understand myself more, despite ending in such a hopeless way. Sylvia’s beautiful writing and depictions of nature give the poem a positive feeling, even with so much despair resting within the lines.

Best Quote: “I am terrified by this dark thing/that sleeps in me;/all day I feel its soft, feathery turnings, its malignity.”

The Jailor

Most readers view “The Jailor” as a poem about domestic abuse; they see the jailor that Sylvia speaks of as a real person in her life. When I first read this poem, I saw the jailor as depression or some other mental ailment that held Sylvia captive and tormented her. Either way, the poem is incredibly dark and powerful. Sylvia does not hold back as she describes the satisfaction her captor gets from her pain. She writes about him burning her with cigarettes and drugging her, all while her “night sweats grease his breakfast plate.” (23). Her captor seems to not only enjoy her suffering, but is also able to forget or distance himself from what he is doing. He has a “high, cold mask of amnesia” and an “armory of fakery” at his disposal (24). Sylvia wants him dead, but feels trapped and powerless, which is at odds with the self-confidence we see in so many of her other poems. This poem is important and powerful as a raw account of real domestic abuse. It is just as important as an exploration of depression as a captor and abuser. At the end of the poem, Sylvia comes to the conclusion that, although she is helpless at the hands of her tormentor, he is also helpless because of her. What would he do without her pain? There is some hope in this last revelation; Sylvia realizes whatever it is that harms her (a real man or a mental illness) is as trapped as she is and is therefore not as powerful as it seems.

Best Quote: “What would the dark do without fevers to eat?/What would the light/do without eyes to knife, what would he/do, do, do without me.”

Medusa

Sylvia’s poem about her father (“Daddy”) is one of her most renowned works, but one of my personal favorites is her poem about her mother, “Medusa.” Sylvia has outdone herself here when it comes to imagery and anger. She has captured the rage of the sea on a page. Throughout the poem, Sylvia vents to a person (her mother) who will not leave her alone. She seems to see her mother as powerful, referring to her as a “God-ball” and a “lens of mercies” (60). However, Sylvia is also disgusted by and terrified of her, describing her as a “fat and red…placenta” who is steaming over the sea towards her (60). The connection between mother and daughter is always “in state of miraculous repair,” even though Sylvia clearly wishes it would be severed. By the end of the poem, Sylvia reaches the crux of her frustration, saying “who do you think you are? A communion wafer? Blubbery Mary?” (61). This language once again presents the mother as a god-like or saintly figure, although this time Sylvia has grown tired of her parent’s holier-than-thou attitude and no longer seems afraid as she did in the beginning of the poem. Sylvia breaks the bond between the two for good with her last line: “There is nothing between us.” (61). I always enjoy reading this poem for its honesty, emotion, and descriptions of the sea. Sylvia entwines nature imagery and rage impeccably.

Best Quote: “I didn’t call you./I didn’t call you at all./Nevertheless, nevertheless/you steamed to me over the sea,/fat and red, a placenta.”

Stings

I see this poem as a shining example of Sylvia’s confidence and bold personality. Here she is a queen, claiming her throne and beyond. In the beginning of the poem she feels vulnerable, using imagery of a worn, tattered queen bee: “her wings torn shawls, her long body/rubbed of its plush.” (86). She feels too weak and downtrodden to rise to the occasion. By the seventh stanza however, Sylvia is prepared to take the reins: “I am in control./Here is my honey machine,/it will work without thinking.” (87). In the eighth stanza, Sylvia brings her ex-husband into the poem, where he is described as watching the proceedings and then leaving. She sees him as deceptive and complicated, but also sweet. His presence and what is revealed about him ultimately does not bring her down; the last two stanzas describe her overcoming death and flying away. The old and worn queen bee she described at the beginning of the poem now has a “lion-red body,” is “more terrible than she ever was,” and flies like a “red comet.” (88). I love how Sylvia portrays herself as infinitely powerful and almost dangerous in this poem. She does not pretend to be a gentle and pure queen, but rather a queen that is like a “red/scar in the sky.” (88). The comets and lions that she mentions have the potential to be destructive, and I see this poem as Sylvia embracing the destructive parts of her nature. I have tried to do the same in my own writing, although not as beautifully as she has.

Best Quote: “Now she is flying/more terrible than she ever was, red/scar in the sky, red comet/over the engine that killed her–/the mausoleum, the wax house.”

What Makes Sylvia a Great Poet?

Since she is a famous, award-winning writer, most will agree that Sylvia Plath has achieved greatness. I have already explored some of the reasons for her greatness above, namely her dedication to the themes of her poetry, the raw honesty of her work, and the beautiful imagery and language she so frequently used. However, I think the true reason for her greatness lies beneath those things. I see Sylvia’s poetry as great because it required personal sacrifice. Her writing led her to pull back the curtains over her life and bare her heart to the world, regardless of consequences. Of course, most poets reveal things about themselves in their work, but reading Ariel gives one the sense that Sylvia has stripped away each layer right to the bone. Her experiences with abuse and suicide were exposed. Her anguish over losing her husband to another woman was revealed. She laid her conflicting feelings about motherhood out for the world to see. These are not easy tasks, but Sylvia performed them powerfully and with little hesitance. Even today she continues to give us pieces of herself through journals, letters, and unpublished poems. Her willingness to be vulnerable has solidified her in America’s memory.

“Looking, With It’s Hooks, For Something To Love”

No writer draws inspiration from thin air. As a confessional poet, much of Sylvia’s work was inspired by her real-life and relationships. After her death, Sylvia’s personal letters were searched through, and every correspondence was analyzed. Two of the most prominent relationships Sylvia had in her life were her friendship with Anne Sexton and her marriage with Ted Hughes. These two relationships shaped her as a person, as well as influenced her writing.

Anne Sexton

Anne Sexton was a controversial Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, known for her book Live or Die. She wrote about topics such as abortion, adultery, addiction, and other taboo subjects. Anne and Sylvia first met in a writing class taught by Robert Lowell, another successful writer at the time. They seemed different on the surface; Anne was described as glamorous and outspoken, while Sylvia was silent and sensible. Despite these differences, they were far from opposites. Both of them had struggled with mental health, stayed at mental institutions, and had attempted suicide. At the time they met, Anne had overdosed multiple times. Their conversations with each other revolved around suicide, mental illness, and their frustrations with the societal expectations they faced as women. Although their friendship was brief, it left a mark on Sylvia’s writing style. In a 1962 interview, she claimed Anne as an influence for her poetry collection Ariel. Anne also found herself influenced by Sylvia, writing a poem entitled “Sylvia’s Death” in 1963.

Ted Hughes

Ted Hughes was a successful English poet who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1984. He is known for works such as Crow, published in 1970, and also for being Sylvia Plath’s husband. The two met at Cambridge in 1956 and married a few months later. At first they seemed to be a match made in heaven as two talented writers who challenged each other to do their best work. Sylvia called Ted “a genius, a great man, a great writer” (Clark, 750). Ted also had great respect for Sylvia. According to their daughter, Freida, Sylvia’s work was of utmost importance to him, “and he saw the care of it as a means of tribute and a responsibility.” (Plath, xvii). Unfortunately, things went wrong for the couple in their last year of marriage. Ted met a woman named Assia and began an affair, which hurt Sylvia’s ego greatly. Her journals and letters to her therapist accuse him of psychological and physical abuse at the end of their relationship, and she calls him “a vampire on my life, killing and destroying us all.” (Clark, 759). Even as he became a more and more difficult husband, Sylvia wanted to work things out, saying that she would have been willing to have a more unconventional marriage, so that he could experience the freedom to drink, travel, and have a few affairs. However, his continued bad behavior “made even this impossible,” according to Sylvia (Clark, 751). Eventually, not wanting to follow in the footsteps of her mother by staying in an unhappy marriage, Sylvia separated from Ted and longed for the completion of the divorce process. She felt that “when I am free of him my own sweet life will come back to me.” (Clark, 752). Sadly this never happened for Sylvia, as she committed suicide before the divorce was finalized.

At the time of her death, Ted did not look good at all. His wife had written an entire poetry collection influenced by him and filled with her rage at him. In addition to Ariel, Sylvia’s journals and letters would continue to leak into the public eye over the years, further painting him as the villain. There have been many conflicting opinions on Ted, and whether or not he deserved the wrath of Sylvia’s fans, which included the attempted removal of his last name from her gravestone and threats against his life. Some feel that the abuse allegations were enough to justify the vitriol he was faced with after her suicide. Others think that he was treated too harshly. Ted’s daughter is among those who defend him, stating that the cruel words said about Ted contrast with the way he “quietly and lovingly” raised her (Plath, xviii). Ultimately we will never know what their relationship was really like, and seeing as both people involved are dead there is little to be done at this point beyond empathizing with Sylvia’s anger and despair.

“It Is They Who Own Me”

Unfortunately, one of the most well-known aspects of Sylvia Plath’s life is her death. The way in which she took her life (putting her head in an oven while her children slept upstairs) is a tragedy, but it has also made a morbidly entertaining story…a story that helped propel her posthumous fame. As Sylvia’s daughter has said: “Ariel’s notoriety came from being the manuscript on her desk when she died, rather than simply being an extraordinary manuscript” (Plath, xviii). As more time passes since Sylvia’s death, she is dissected again and again, along with her work, and it has become hard for people to see the difference between truth and fabrication. Who was Sylvia Plath? It is more difficult than ever to know. Was she…

A Feminist Icon?

A large part of Sylvia’s legacy is built upon the idea that she was a feminist icon. Some of this opinion has been formed from Sylvia’s work, and other parts have been formed from her life and relationships. “The Detective,” “Lady Lazarus,” “Lesbos,” and “The Applicant” are full of Sylvia’s frustrations with the role she was expected to fill as a woman in the 1950s and 60s. I already touched on Sylvia’s distaste for marriage and housewife duties in the section about Ariel, but Sylvia has made these same feelings clear in many other places in her work and life. In The Bell Jar for example, the character of Esther talks about how she “hated the idea of serving men in any way.” A direct quote from Sylvia herself states: “I am envious of males. I resent their ability to have both sex (morally or immorally) and a career.” (Clark, 185). In addition to her envy of male privilege, Sylvia hated the idea of being a wife/mother with no other ambitions. She refused “to be a Wife-mother every minute of the day” and also abhorred “the role of passive, suffering wife.” (Clark, 732-733). Sylvia did love her children and found fulfillment in raising them, but she was always searching for something more. Sylvia’s relationship with Ted Hughes also fed into the “feminist icon” idea of her. Other women who had experienced cheating and/or abusive husbands could relate to and felt empowered by Sylvia’s open anger at Ted.

It is undeniable that, in a time when American women had trouble getting credit cards, could be fired for being pregnant (McGee & Moore), and could not purchase birth control in some states (PBS), Sylvia’s continued criticisms of the status quo were needed and certainly added to the feminist movement, especially after she reached peak fame after her death. However, there are those who believe that the title of “feminist icon” is ill-fitting. Freida Hughes felt that her “mother’s suicide, rather than her life, was really the reason for her elevation to the feminist icon she became” (Plath, xviii). It has also been pointed out that The Bell Jar has several outdated, racist remarks in it, and that Sylvia’s poetry collection has the same issue (a slur is present in the poem “Ariel,” for example). This being the case, it seems wrong to give a person who has written such things the “icon” label. In my opinion, Sylvia has been put on too much of a pedestal, as many celebrities have been, and she has also made many mistakes. That being said, it is obvious that Sylvia aided the feminist movement with her writing, even if she does not fully deserve the “feminist icon” title.

A Bad Influence?

Despite being a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, there are many who do not take Sylvia seriously, and believe her and those who read her poetry to be a joke. A certain stereotype has emerged about people who read Sylvia Plath. One article describes the typical Plath reader as an “angsty, depressed teen girl who takes herself too seriously.” (Herndon). Another similar article talks about “Plath the crazy girl, and the crazy girls who love her, all of whom are seen as young, starry-eyed fools in need of scolding.” (Van Duyne). I have witnessed this stereotype in action myself, when I was reading through reviews of The Bell Jar. One commenter left a scathing review of the book, which seemed to be more about the girls in her high school class who read Sylvia’s work rather than the contents of the book itself. The commenter saw the girls as pathetic and insane, and extended her perception to Sylvia’s novel. Sadly, it appears Sylvia has garnered a reputation for being a bad influence on young women. This reputation, as far as I can tell, is undeserved. Yes, Sylvia suffered from severe depression, as well as various traumatic experiences throughout her life, and yes, she documented these experiences in writing. Her writing, described as “confessional,” is tragic, terrifying, and dark, but it also has its hopeful and uplifting moments. Frieda Hughes points out in the foreword to Ariel that the original collection started with love and ended with spring. Sylvia’s strength also comes through in both her poetry and in her personal letters. For example, during her separation from Ted Hughes she seemed focused on how good her life could be without him rather than wallowing in anguish at his affair. She shows confidence and power in poems such as “Stings” and “Ariel,” and even The Bell Jar has a hopeful ending with Esther leaving the hospital and thinking about returning to school. If young women are really paying attention to Sylvia’s poetry, they will not only take in the difficult, disturbing portions of it, but also the signs of spring that Sylvia leaves a trail of throughout her work.

The Ever-Vengeful Wife?

Out of all of the things Sylvia’s name has been tied to after her death, her relationship with Ted Hughes is perhaps the one that would have annoyed her the most. While it is true that Ariel is filled with anger at him, and she suffered as a result of his affair and his abusive behavior, her letters (after an initial mourning period) show signs of her wanting to move on. She wrote to her mother about her excitement at the prospect of starting a new life without him, and looked forward to surrounding herself with “intelligent good people.” (Clark, 778). In October 1962 she seemed to have gotten over her husband: “Ted is dead to me, I feel only a lust to study, write, get my brain back and practice my craft” (Clark, 779). Unfortunately, the decades of readers who showed up after her death refused to let her association with Ted go. This is because, as Frieda Hughes writes, “when she died leaving Ariel as her last book, she was caught in the act of revenge.” (Plath, xx). Ariel remains stagnant, not growing and evolving as Sylvia would have done if she had remained alive. The outdated language used in some of the poems are testament to this. In a way, Sylvia has been frozen in time, trapped in the house where she died, trapped in her opinions and views at that time, and trapped in her marriage to Ted Hughes. I hope future readers will have the decency to set her free.

Now that I’ve shared the opinions of others, I should probably add my own thoughts. My personal feelings about Sylvia Plath are as confusing and complex as the web of half truths that have been written about her. I can relate to her work, especially the poem “Elm” and her novel, The Bell Jar. She has a writing style that I enjoy; I love the way she combines elements of the natural world, beautiful language, and dark content. When it comes to her as a person, I feel it is important to admit that I don’t know much. Even with her personal letters and journals being published, I don’t feel comfortable making too many assumptions. Based on her writing, it seems she was a passionate person, who was incredibly self-confident to the point of looking down on others at times. Her depression got to her despite her considerable strength. She was studious and perhaps a workaholic. Some of her views were admittedly outdated and harmful. She wanted a better life for women. Perhaps one or many of these things are untrue; after all, I haven’t had a conversation with her. I am just adding my own perception of Sylvia into an ocean of other opinions and assumptions. Ultimately, I think she is someone we can learn from. We can try to avoid her mistakes, but copy her hopeful attitude and strength. I will be keeping this line from “Stings” close to my heart: “They thought death was worth it, but I/have a self to recover, a queen.” (Plath, 88).

Sources

Beam, Alex. “The Mad Poets Society.” https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theatlantic.com/amp/article/302257/

Clark, Heather. Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath. Penguin Random House, 2020.

Crowther, Gail. “On the Friendship and Rivalry of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.” https://lithub.com/on-the-friendship-and-rivalry-of-sylvia-plath-and-anne-sexton/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Lobotomy.” https://www.britannica.com/science/lobotomy

Ford, Mark. “‘Lady Lazarus’ by Sylvia Plath: a close reading.” https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/a-close-reading-of-lady-lazarus

Ford, Mark. “A close reading of ‘Ariel.’” https://bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/a-close-reading-of-ariel

Herndon, Jaime. “Dead Woman Poets Are Not Your Punchline.” https://www.google.com/amp/s/bookriot.com/sylvia-plath-and-anne-sexton/amp/

History.com. “Poet Sylvia Plath is Born.” https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.history.com/.amp/this-day-in-history/sylvia-plath-is-born

McGee, Susan & Moore, Heidi. “Women’s rights and their money: a timeline from Clepatra to Lilly Ledbetter.” https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/money/us-money-blog/2014/aug/11/women-rights-money-timeline-history

Metzl, Jonathan. “‘Mother’s Little Helper’: The Crisis of Psychoanalysis and the Miltown Resolution.” https://www.med.umich.edu/psych/FACULTY/metzl/07_Metzl.pdf

Pbs.org. “A Timeline of Contraception.” https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-timeline/

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. Harper & Row, 1971.

Plath, Sylvia. Ariel: The Restored Edition. HarperCollins, 2004.

Sadowsky, Jonathan. “Electroconvulsive Therapy: A History of Controversy, but Also of Help.” https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/electroconvulsive-therapy-a-history-of-controversy-but-also-of-help/

Van Duyne, Emily. “Why Are We So Unwilling to Take Sylvia Plath at Her Word?” https://lithub.com/why-are-we-so-unwilling-to-take-sylvia-plath-at-her-word/