Or: How I learned to stop worrying about the Bomb and love my Rothko prints.

The Cold War lasted nearly fifty years and was waged on multiple fronts, but the real fighting was for the hearts and minds of the enemy citizens. Souls, not geography, were the prize. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Britain’s MI6, and the USSR’s KGB were renowned for their prolific efforts centering around creative, if not always effective propaganda. Some forms were overt. Sports, for example. Every four years, the capitalist West went head-to-head against the commie East in the Olympics. The country that collected the most medals was presumed to have the better politico-economic system. (When the West prevailed, chemist’s heads rolled in the Soviet juvenile athlete doping department. Alternately, when the Soviets were victorious, I imagine the chemists had their families returned to them alive and well.) While the CIA was playing a passable game of three-dimensional chess, the comrades at the KGB were determined to bend the world’s collective will to their ideological oar by any means of indoctrination necessary. (An extra ration of potato vodka probably helped for motivation.) Wherever either side could inject its values into the popular consciousness without getting caught, they did. From James Bond to the modern art movements and a raft of familiar cultural icons and historical events, the world was under as much threat of being brainwashed as it was of being vaporized by the Bomb.

The Cold War in Paper Propaganda

Propaganda literature in the form of the now classic espionage thriller, was practically birthed by spy masters like John Le Carre (real-life UK spy, real life name David Cornwell[1]), best known for his novel, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold among many others. And let’s not forget about Ian Fleming whose titular James Bond character became synonymous with British espionage (and the annoying affectation of introducing himself by his surname, followed by his full appellation). The character sports the most fashionable Saville Row finery a government employee can afford, pilots a bespoke sports car – easily worth quadruple his salary – with bleeding-edge weapons tech and integrated countermeasures for every inevitability. He’s dashing, patriotic, and always up for a quickie. (I presume this was frowned upon in the frigid motherland.) The Soviets had their own dismal version of Bond named Maxim Isaev born of Yulian Semyonov’s spy novels, which were considered the most popular of the communist era.[2] Isaev. Maxim Isaev. Rolls of the tongue, no?

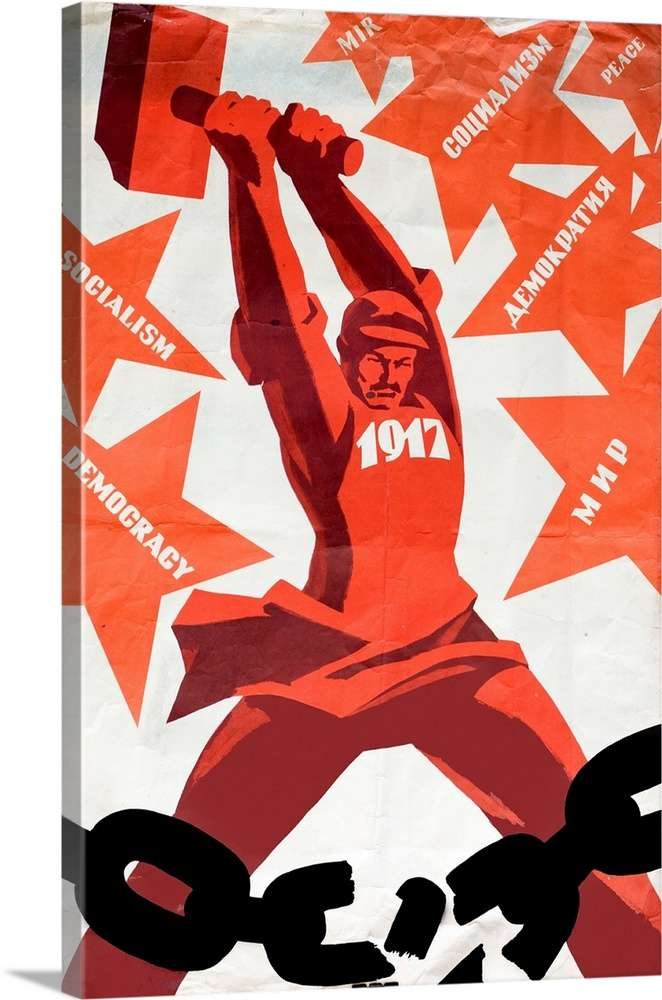

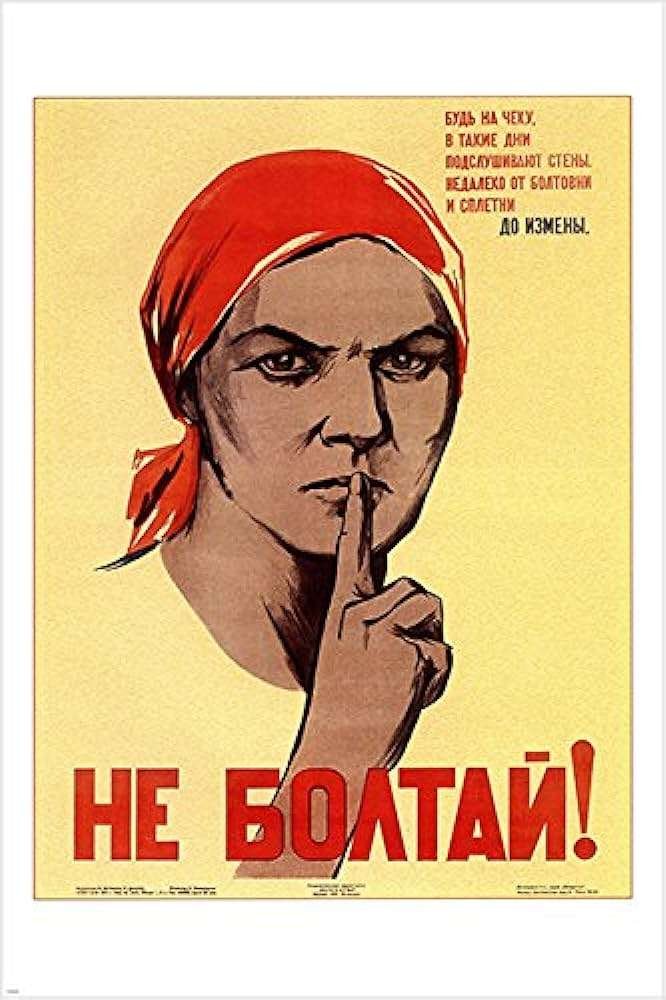

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union continued building bombs and pursuing dehumanizing policies while continuing to fight dissidents with a surfeit of posters and began sentencing another generation of writers, artists, gays, Jews, and political contrarians to the gulag. Oh, but they did produce more posters. So, so many posters.

Film and Radio Supercharge Superpower Propaganda

If a Soviet criminal dissident were extraordinarily lucky, there might be a radio in the gulag capable of picking up frequencies as signals from around the world as they bounced off the ionosphere and refracted back to Siberia. But on the off-chance one of them found a four-leaf clover under the permafrost and wished for a radio…

The wireless, relatively new to consumers but common in military and espionage circles since the Titanic disaster of 1912, became an instant propaganda tool, regularly deployed to deliver coded messages to the Allies via The Voice of America broadcast. In response to the intrusion, the Soviets jammed the signals of 1,000 broadcast radio stations they believed were designed for this purpose.[3] Punishment for listening was imprisonment.[4]

Never to be outdone (or outspent), the CIA commissioned an animated version of George Orwell’s anti-pinko allegory, Animal Farm.[5] Scoring a distribution deal behind the iron curtain was about as likely as Khrushchev handing over the keys to the Berlin Wall, but the film was directed at an American audience anyway. Yup, the military industrial complex propaganda machine targeted the minds of both American and Soviet citizens. Did you think we were immune? Duck and cover!

M.A.D. Strategies: Mutually Assured Dance?

American and Soviet dance companies performed regularly around the world, attempting to demonstrate cultural superiority and assert dominance. Surely, yet another aspect of the “mine is bigger” game being played on a global scale. This artistic arms race led to a dramatic rise in U.S. government funding for touring orchestras, jazz bands, and solo musicians attempting to demonstrate the artistic advantages of capitalism.[6] Some of the Russian dancers were moved by what they heard and, in 1961, Soviet dancer Rudolf Nureyev defected to the UK to perform with Britain’s Royal Ballet. Premier Khrushchev wasted no time signing his death warrant. Alas, the old shoe-banger missed and Nureyev survived another thirty-two years.[7]

Fresh out of easy answers that didn’t end in a nuclear holocaust, American, British, and Russian spy agencies attempted to harness the occult for their respective propaganda shows – employing psychics for their “telepathic powers” to facilitate long distance communications over enemy lines and “telekinesis” to ward off missile attacks.[8] Reports on their efficacy remain deeply, deeply classified (and probably wicked embarrassing).

Enforcing the Communist Ideal

Despite “owning” one of history’s most prodigious propaganda machines, the Soviets were creatively and financially limited to churning out ponderous patriotic posters with slogans like “The goal of the alliance is to destroy bourgeois domination of the proletariat” and “Long live the USSR, model of brotherhood among workers of world nationalities!”[9] Their propaganda posters were designed to provoke heroism, pride, optimism, and unquestioning commitment to the revolution. Subject matter could include “lazy workers” not doing their part for the system, “heroic workers” enjoying the fruits of communism as they labored in the fields or factories, and of course, promotion of the communist ideal ad nauseum. Good Soviet citizens were idealistic, athletic, educated, patriotic, hard-working, self-sacrificing and, obviously, good looking enough to be on a poster. The CCCP was confident that posters were the most effective propaganda weapon in their arsenal. Convinced of the value of his propaganda, Khrushchev ordered all posters guarded from tampering by including a warning a la the Surgeon General’s warning on a pack of cigarettes. “Anyone who tears down or covers up this poster is committing a counter-revolutionary act.”[10] (The unspoken punishment being a living death in the Lubyanka basement.)

Enter the Abstract Expressionists

The best propaganda – regardless of media – provokes a visceral, motivating response such as a desire fight for freedom, to eliminate saboteurs, or toast nostroviya with your local party boss over shots of state-distilled vodka. Results were consistent and binary: propaganda was thought-provoking or thought eliminating and was always subtle enough to slip in under the radar of human consciousness without triggering a critical thought in response. The American public’s fear of the red menace did not extend to the abstract expressionists. Precisely because modern art was not universally popular, and was created by artists who openly disdained orthodoxy, that it was such an effective tool in showcasing the fruits of American artistic freedom to anyone looking in from the outside.[11]

President Truman personally considered modern art, “merely the vaporings of half-baked lazy people.”[12] But he did not declare it degenerate and expel its practitioners to gulags in Alaska (the US equivalent of Siberia?). Rather, he saw abstract expressionism as a direct repudiation of Soviet Socialist Realism. Nelson Rockefeller liked to call them the “Free Enterprise Painters.”

Alternatively, the Soviet Union’s “Popular Front,” the New Yorker magazine snarked, referred to the political role of American Modernism as “The Unpopular Front.” [Emphasis mine.] The very existence of Modern Art proved to the world that its creators were free to create, whether you liked their work or not.[13]

President Dwight Eisenhower took a more nuanced, constitutional approach. “As long as American artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in [a system of] tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and tools of the state; when artists become the chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested, and creation and genius are destroyed.[14]

Abstract expressionism was virtually the visual analog of modern jazz as defined by its rejection of conformity, non-objective imagery, spontaneous and personal expression, and gestural brushstrokes characterized by bold, sweeping motions (always freely expressed).[15]

Building the American Propaganda Machine

Most thoughtful art collectors understand the works they collect are reflections of their tastes and imply their values – or lack thereof. The CIA was no different and began to promote and develop its own collection of abstract art for the sake of making abstract expressionism synonymous with individual expression and the freedom of subjectivity.[16]

Getting museums on board with CIA’s mission was easy as tapping Nelson Rockefeller, then president of the Museum of Modern Art, who helped the complex cold war propaganda mission by assisting in its acquisition of abstract paintings by Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollack, and Willem De Kooning among others.[17] The world was put on notice: these were the most important artworks of the time.

Another path to opening the eyes of the menacing red artists lay in the expressive potential of color. Mark Rothko pioneered paintings based on simplified, large-format, color-dominated fields. The impulse was, in general, reflective, and cerebral, with pictorial means simplified to create a kind of elemental impact. Rothko spoke of his goal to achieve the “sublime” rather than the “beautiful.”[18] His Soviet counterparts were more concerned with Soviet Socialist Realism as defined by the optimistic youthfulness of its subjects and their pro-pinko poster proclivities.

Rothko intended his glowing, soft-edged rectangles of luminescent color to provoke a quasi-religious experience, even eliciting tears. As with Jackson Pollack and other abstract expressionists, scale contributed to the meaning. For the time period, the works were vast. The average size of Rothko’s untitled color field paintings was 60.4” x 52.6”.[19] They were also meant to be seen in relatively close quarters, so that the viewer was virtually enveloped by the experience of confronting the artwork. Rothko said, “I paint big to be intimate.” The notion is toward the personal authentic expression of the individual rather than the grandiose.[20] It goes without saying that Soviet artists were rarely allowed to speak so many contiguous sentences, let alone free to express themselves without a long-term detour to Siberia.

Ironically, Rothko’s main concern was that people might want to buy his paintings because they were fashionable, not because they were moved by them. He is said to have refused to sell canvases to people who “did not react correctly” to the paintings in his gallery. I can’t help but think this was not the action of a capitalist, at least not one whose character was dominated by avarice.

It should be noted that Rothko’s sentiments were not with the capitalists but the socialists. Nevertheless, like every artist since the first Neanderthal painted a wobbly bison on a Spanish cave wall, money talks and communism walks. The modern expression “everybody’s gotta eat,” applied equally to starving artists on both sides of the Berlin Wall. Whatever position an artist chose, at the end of the day they required the same basic nutrition as the rest of us.

Happy Hour Capitalism Refutes Crony Capitalism

In terms of Rothko’s inner battle waged between his art and the contents of his refrigerator, perhaps the most infamous, yet sublime of Rothko’s works were The Seagram’s Murals. Commissioned by the famous booze manufacturer to provide murals for their new Manhattan restaurant, The Four Seasons. Rothko set about creating forty canvases in dark red and brown to adorn the walls of the prestigious dining establishment. He chose to orientate his blocks of color on an uncharacteristic vertical plane, in an effort, he claimed, “to make the diners uncomfortable as they ate their over-priced meals.”[21]

However, before the restaurant opened, Rothko had a change of heart. Overcome by his socialist sensibilities, he returned his advance, claiming that he could not continue to work where so many disgusting capitalists would dine with impunity. (Presumably not on children, but actual food like steaks, pastas, salads, and stuff.) Rothko decided to secret the murals away in his studio. Today, the collection has been broken up, with some murals in London’s Tate Modern, some in Japan’s Kawamura Memorial Museum, others in The National Art Gallery in Washington DC[22]. To this day, The Seagram’s Murals appear ubiquitously in pop culture – one even hangs in Bert Cooper’s office in Mad Men.[23]

By 1950, this format of rectangles of color within a larger color field had become one of the most important features of Rothko’s work.[24] In fact, his color field experiments were an exercise in his ability to contain a vast array of colors of differing hues in differing proportions on the same plane. When you Google the works of Mark Rothko, his color fields dominate his abstract paintings, but he also offers a glimpse of himself in a self-portrait that itself feels composed of hundreds of mini-color fields, almost like pixels!

After hours staring at a print of Green and Tangerine (1956), I can’t help but second guess myself. Am I feeling what Rothko intended? Are the colors reaching me viscerally or do I just like the painting because its name rhymes? Then I wonder: if I were a Russian artist arm-twisted into illustrating cartoonishly optimistic characters for a necrotic totalitarian state, what would the works of the abstract expressionists say to me?

Freedom.

- https://www.npr.org/2023/10/27/1209012058/novelist-john-le-carre-reflects-on-his-own-legacy-of-spying#:~:text=John%20le%20Carre%20was%20his,its%20foreign%20intelligence%20service%2C%20MI6. ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yulian_Semyonov ↑

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/cold-war-propaganda/FD4E98F49AE175545A642926A68B62CB ↑

- https://www.tedlipien.com/2022/12/29/why-voice-of-america-and-bbc-had-no-russian-language-broadcasts-until-after-wwii/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CRussians%20caught%20listening%20to%20VOA,received%20by%20their%20Russian%20audience. ↑

- https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/cold-war-propaganda/#:~:text=In%20the%201950s%20the%20CIA,government%20%E2%80%93%20to%20serve%20as%20propaganda.&text=Movies.,communism%20to%20the%20big%20screen. ↑

- https://daily.jstor.org/was-modern-art-really-a-cia-psy-op/ ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Nureyev ↑

- https://listverse.com/2016/04/28/10-crazy-cold-war-schemes-that-were-completely-serious/ ↑

- https://sites.baylor.edu/keston-collections/2022/06/08/propaganda-in-color-examining-soviet-era-posters-with-hist-4379-the-cold-war/ ↑

- https://sites.baylor.edu/keston-collections/2022/06/08/propaganda-in-color-examining-soviet-era-posters-with-hist-4379-the-cold-war/ ↑

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/10/17/unpopular-front ↑

- https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1952/12/14/93390398.html?pdf_redirect=true&site=false ↑

- ↑

- xiii https://suitesculturelles.wordpress.com/2017/03/07/abstract-expressionism-and-the-cold-war/ ↑

- https://www.theartstory.org/movement/abstract-expressionism/ ↑

- https://www.sartle.com/blog/post/abstract-expressionism-and-the-cold-war ↑

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/10/17/unpopular-front ↑

- ↑

- https://www.artnome.com/news/2018/9/26/quantifying-mark-rothko ↑

- Ibid ↑

- https://www.markrothko.org/seagram-murals/ ↑

- https://www.markrothko.org/ ↑

- https://stuartmorris.co.uk/2014/10/08/mystery-behind-rothkos-seagram-murals/ ↑

- https://www.markrothko.org/biography/