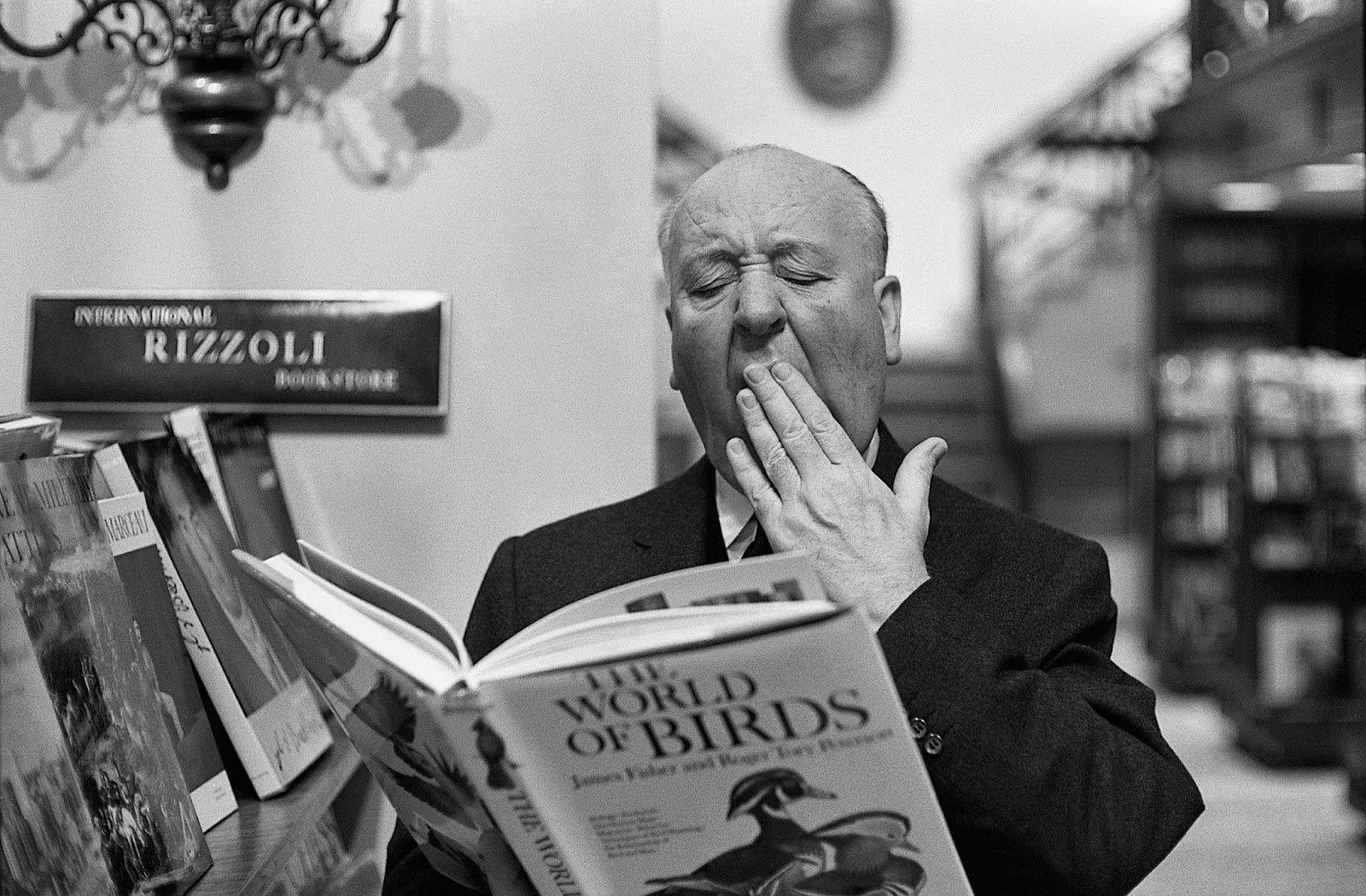

Like most Americans I grew up with Alfred Hitchcock movies. It was a family tradition to watch Hitchcock mystery and film noir thrillers with some of the most iconic Hollywood stars of all time.

Alfred Hitchcock (1899- 1980) was a British film director. Known as the ”master of suspense”, considered as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time. His career spanned over six decades directing over 50 films, winning six Oscars with four nominations. Famous actors that performed in his films include Grace Kelly, Cary Grant, Ingrid Berman, James Stewart, Kim Novak, Tippi Hedren, Sean Connery, Paul Newman, Eve St. Marie, Henry Fonda, Doris Day, Gregory Peck, Laurence Olivier, Joan Fontaine, and many others.

Hitchcock began his career in the silent film era, cutting his teeth on various projects before directing his first full-length feature, The Pleasure Garden, in 1925. However, it was The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927) that truly marked his arrival as a formidable director. This silent thriller, with its innovative use of shadows and tension, hinted at the greatness to come.

Hollywood and the Golden Age

In 1939, Hitchcock made the leap to Hollywood, a move that would cement his legacy. He kicked off his American career with Rebecca (1940), a haunting tale that won the Academy Award for Best Picture. But Hitch, as his friends called him, was just getting started.

The 1950s and 1960s were his golden years, producing a string of masterpieces that have since become cinematic lore, Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960). Psycho, in particular, was a game-changer. The infamous shower scene, with its rapid cuts and shrieking violins, is etched into the collective consciousness, a testament to Hitchcock’s genius for turning everyday scenarios into nightmares.

Hitchcock wasn’t just a storyteller, he was a magician, a puppeteer pulling the strings of his audience’s fears and desires. He pioneered the use of the camera to reflect a character’s gaze, developed the MacGuffin to drive his plots, and mastered the art of suspense, keeping audiences teetering on the edge of their seats, desperate for resolution.

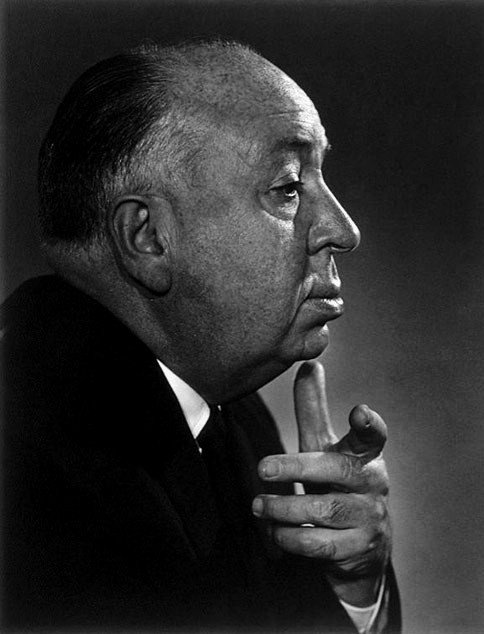

The Man Behind the Curtain

Despite his genial public persona, Hitchcock was a complex man. His films often explored themes of voyeurism, identity, and the thin veneer of normalcy. Off-camera, he was known for his meticulousness, often pushing actors to their limits to achieve the perfect shot. Stories of his demanding nature and peculiar sense of humor abound, painting a picture of a man as enigmatic as his films.

Hitchcock’s influence on cinema is immeasurable. His work has inspired countless directors, from Martin Scorsese to Guillermo del Toro. The term “Hitchcockian” has become shorthand for a particular style of tension and psychological depth, a nod to his enduring legacy. Hitchcock left behind a body of work that continues to thrill, chill, and mesmerize.

Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense, a man who turned psychological terror into an art form, all while wearing that smug little smirk like he knew more than anyone else in the room. And he probably did. Born in 1899 in London, this portly gentleman didn’t just direct films, he manipulated audiences with the precision of a surgeon performing an autopsy. Every frame, every shadow, every twist of the knife (both metaphorical and literal) was a carefully placed piece of his cinematic puzzle.

Hitchcock was all about fear, primal, raw, but never overt. He once said, “There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it.” And wasn’t that his style? He preferred to let tension simmer, stretch out like a cat ready to pounce, only to reel you back just when you thought it was safe.

In “Psycho” (1960), he redefined horror with that infamous shower scene, one that sent so many screaming into their bathtubs, locking the doors behind them. Poor Marion Crane… if she only knew who was lurking behind that curtain. He toyed with sexual tension, too, just look at “Vertigo” (1958), or the seductive cat-and-mouse games in “Rear Window” (1954) and “To Catch a Thief” (1955).

Now, about his legacy. Hitchcock’s influence is tattooed into the very flesh of modern cinema. He practically invented the thriller genre, giving filmmakers the tools to make audiences squirm, gasp, and cling to their popcorn for dear life. And let’s talk about his ability to twist human psychology like a snake around a branch. Characters who aren’t what they seem, the hidden darkness within everyday life, he tapped into that paranoia, made you question everything.

But, like any genius who thrives in shadows, he had his demons. Controlling, obsessive, especially with his leading ladies. His icy blondes, like Grace Kelly and Tippi Hedren, were more than muses, they were puppets, molded into his vision of perfection. Dark, isn’t it? He wasn’t a saint, and perhaps that’s part of what makes him so fascinating, a complex, flawed man who created equally complex, twisted stories.

We can’t forget that the world of suspense isn’t just about what’s lurking in the dark, but the monsters hiding within the mind. Hitchcock understood that better than anyone. In the end, Alfred Hitchcock left us with a treasure trove of nightmares, reminding us that fear, when wielded right, is the ultimate aphrodisiac. And he wielded it like a scalpel.

“Vertigo” with James Stewart and Kim Novak.

Early British Period (1920s–1930s)

The Pleasure Garden (1925) – A silent film and his first feature. A quaint start, but little did audiences know what was brewing beneath that calm exterior.

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927) – Now we’re talking! This is where Hitch starts showing his true form, playing with the theme of the “wrong man” and cranking up the suspense.

Blackmail (1929) – The first British talkie. He knew how to make the sound of footsteps or the rustling of a newspaper feel like nails on a chalkboard.

The 39 Steps (1935) – A classic deliciously taut thriller about spies, the wrong man trope again, and a gorgeous mix of tension and romance. Ah, the formula works. Starring Robert Donant and Madeline Carroll.

The Lady Vanishes (1938) – Another classic with a touch of humor, but still packed with mystery. An old woman disappears on a train. Seems innocent enough, but nothing is ever as it seems in Hitch’s hands. Stars Michael Redgrave and Margret Lockwood.

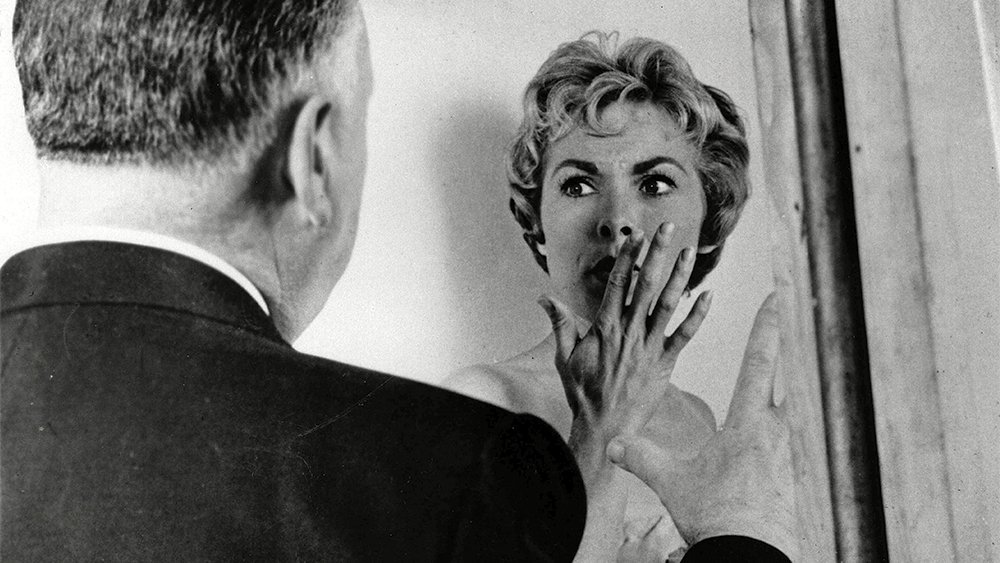

Hitchcock directing Janet Leigh in “Psycho””

Hollywood Period (1940s–1960s)

Rebecca (1940) – His first American film, and it won the Oscar for Best Picture. Gothic romance with a side of psychological torment. Starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine.

Suspicion (1941) – Starring Cary Grant and Joan Fontaine. A delicious tale of paranoia, perfect for a little late-night anxiety.

Shadow of a Doubt (1943) – Hitchcock’s personal favorite. A young woman discovers her charming Uncle Charlie may not be as sweet as he seems. Spoiler: He’s a killer. Stars Joseph Cotton and Teresa Wright.

Notorious (1946) – Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in a blend of espionage, betrayal, and fiery chemistry. Oh, and Nazis—let’s not forget those.

Rope (1948) – Filmed in long takes to feel like a single shot. Two men kill for fun and then throw a dinner party with the body still hidden in the room. Dark and stylish, just like me. Stars James Stewart.

Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in “Suspicion”.

Golden Age of Suspense (1950s–1960s)

Strangers on a Train (1951) – Swapping murders? What could go wrong? The tension is enough to strangle you. Stars Farley Granger and Robert Walker.

Dial M for Murder (1954) – A twisted little yarn about murder, marital distrust, and a perfectly diabolical plan, Starring Grace Kelly and Ray Milland.

.

Rear Window (1954) – Oh, the voyeurism. A man watches his neighbors through his window and thinks he sees a murder. It’s pure, delectable suspense with of Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly.

To Catch a Thief (1955) – Cary Grant and Grace Kelly prancing around the French Riviera. The calm before the storm.

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) – A remake of his own 1934 film. The stakes are high when a child gets kidnapped and only the parents can stop an assassination. Starring James Stewart and Doris Day.

Vertigo (1958) – Hitch’s twisted obsession with control and identity plays out in this fever dream of desire, deception, and tragedy. It’s the kind of psychological torment that lingers in your brain like a bad romance. Stars James Stewart and Kim Novak.

Grace Kelly and Jams Stewart in “Rear Window”.

North by Northwest (1959) – Cary Grant running from crop dusters. If you haven’t seen this one, you simply don’t know thrillers.

Psycho (1960) – The shower scene. Need I say more? It’s the film that redefined horror, and Hitchcock slashed away at the happy illusions of suburban America with every frame. Starring Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins.

The Birds (1963) – Nature bites back. Birds turn vicious, and it’s as much a psychological horror as it is a survival thriller. There’s something delicious about watching an idyllic town crumble under a wave of feathered fury. Starring Tippi Hedren and Robert Taylor.

Later Works (1960s–1970s)

Marnie (1964) – Psychological thriller, twisted romance, and enough Freudian tension to fill a therapist’s office for weeks. Starring Sean Connery and Tippi Hedren.

Torn Curtain (1966) – Paul Newman and Julie Andrews in a Cold War thriller. Not his best, but still, there’s some fun to be had.

Frenzy (1972) – His return to the UK brought out some old demons. Serial killers and suspense—the kind of thing that makes your skin crawl in the best possible way.

Family Plot (1976) – His final film. A lighter crime thriller, almost like a wicked little send-off.

Cary Grant in “North By Northwest”.

Early Life and Beginnings

Alfred Hitchcock’s beginnings were anything but glamorous, yet they sculpted him into the cinematic genius we know. Born on August 13, 1899, in Leytonstone, little Alfred grew up in a strict, Catholic household.

Ah, the drama begins early, doesn’t it? Little did they know, their cherubic son would grow up to redefine the very fabric of cinematic suspense. Hitchcock’s early years were marked by a fascination with the macabre, perhaps fueled by the strict Jesuit school he attended. This combination of discipline and dark curiosity was a cocktail that would later flavor his films with a unique edge.

Alfred Joseph Hitchcock lived in the unassuming suburb of Leytonstone, London. Born to William Hitchcock, a greengrocer, and his wife, Emma, Alfred was the youngest of three children. The Hitchcock family lived a modest life above the grocery shop, where young Alfred often helped his father, learning the value of hard work and the intricacies of human behavior, customers’ quirks and secrets that would later feed into his understanding of character and narrative.

A strict upbringing, the Hitchcock household was governed by a strict Roman Catholic faith, with Alfred attending the Jesuit-run St. Ignatius College. The Jesuits, known for their rigorous and disciplined approach to education, instilled in Hitchcock a sense of order and a fear of authority. These formative years were marked by a blend of rigid discipline and religious instruction, which Hitchcock often remembered with a mix of reverence and resentment. One particularly famous anecdote from his childhood involved his father sending him to the local police station with a note asking the officer to lock him up for ten minutes as punishment for misbehavior. This incident left a profound mark on young Alfred, embedding a lifelong fear of police and authority figures, which he would later exploit in his films to evoke tension and fear.

Amidst this disciplined upbringing, Hitchcock’s fascination with the macabre began to take root. As a child, he was captivated by the tales of Edgar Allan Poe and the ghastly illustrations in The Strand Magazine. This early exposure to gothic horror and suspense ignited a spark within him, one that would later blaze into a full-fledged career.

After completing his schooling, Hitchcock attended the London County Council School of Engineering and Navigation in Poplar, where he studied mechanics, electricity, acoustics, and navigation.

His technical education provided him with a solid foundation in understanding the mechanical aspects of filmmaking, which he would later integrate with his creative vision. In 1915, Hitchcock took a job as a technical clerk at the Henley Telegraph and Cable Company. Though the job was far removed from the world of cinema, it honed his meticulous attention to detail and organizational skills, traits that would become hallmarks of his directing style.

Hitchcock’s entry into the film industry came in 1920 when he joined the London branch of the American company Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount Pictures) as a title card designer. This seemingly humble position allowed him to immerse himself in the filmmaking process, learning the ropes from the ground up. His talent and ambition quickly caught the attention of his superiors, and he was soon promoted to the role of assistant director.

His first directorial effort came with the silent film Number 13, although the project was never completed due to financial difficulties. Despite this setback, Hitchcock’s determination remained unshaken. He continued to work on various projects, slowly building a reputation for his innovative ideas and keen visual style.

By the time he directed The Pleasure Garden in 1925, Hitchcock had already begun to develop the unique narrative techniques and visual storytelling that would define his career. His early films, though modest in budget and scope, displayed a burgeoning genius for suspense and a deep understanding of human psychology.

Grace Kelly in “Dial M for Murder”.

Hitchcock’s legacy

His legacy stretches far beyond just these gems, every twist, every shadow, every ominous note. He didn’t just make films, he made nightmares, and oh, how sweetly they still haunt us. His legacy isn’t just a flickering shadow on the walls of film history, it’s the foundation upon which so many modern genres, and minds, have been built. Hitchcock was the grand architect of suspense, with an eye for psychological tension, misdirection, and the delicious torment of the audience.

What he did, with his sleek, perverse grin, was master the art of showing you just enough, teasing, provoking, and pushing you to the edge of your seat until you were practically begging for the reveal. He didn’t just make thrillers, he made you feel like you were part of his little sadistic game, and you loved it. His influence on film noir was significant, it’s dripping from every shadowy alley, every morally ambiguous anti-hero, and every dangerous femme fatale that strolls through a rain-soaked cityscape.

Grace Kelly and Cary Grant in “To Catch a Thief”.

Hitchcock laid the groundwork by blending suspense with psychological depth, much like film noir does, where motivations are murky, morality is more flexible than a cat burglar, and trust is always a dangerous game. He painted his worlds in shades of gray, where the innocent isn’t always pure, and the guilty, well, they might just be the ones you root for. Think of films like Vertigo, were obsession and madness blur reality, a film noir fever dream before its time.

Modern neo-noir directors sip from Hitchcock’s poison chalice with glee. David Fincher is practically his cinematic heir, especially in films like Seven and Zodiac, soaked in moral decay and the hunt for truth through lies. Even Christopher Nolan can’t escape Hitchcock’s ghost, with Memento turning amnesia into a dark spiral of deception and identity, a twisty mystery that would make Hitch proud.

In essence, Hitchcock isn’t just a grandfather figure you tip your hat to in film history class. He’s the elusive figure in the trench coat, walking just ahead of you in the fog, always a step ahead, daring you to catch up while knowing full well you never will. Neo-noir has taken his cues and upped the ante, playing with the moral ambiguity and psychological intrigue that Hitchcock perfected.

References

IMDB

TCM

Rotten Tomatoes

Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, Patrick McGilligan, Regan Books, NY, 2003.

The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, Donald Spoto, Da Capo Press, NY, 1999.