My parents grew up in the 1930s at the time of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, and they enjoyed reliving those parts of their youth. As my sisters and I grew up, my parents shared their appreciation of Berlin-Porter-Gershwin-Kern musicals, as well as, swing and big band music—this included watching Astaire and Rogers movies on TV.

I have always enjoyed the Fred and Ginger movies which were captivating entertainment – the music, the dancing, and the hilarious situation comedy. It is easy to call them Fred and Ginger because I have known the dancing duo all my life and have been in awe of their elegance, style, and dance virtuosity.

Many years later, when I got interested in Swing, Latin, and Ballroom dancing, I instinctively watched the Astaire and Rogers films to study their dance moves and style. It wasn’t easy; I gained a whole new appreciation of just how sophisticated their dancing was, or still is, in our collective memory.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers represent the epitome of film’s romantic dancers—they are considered the greatest dance team in the history of American film, and their virtuosity and elegance is unparalleled. These two individuals became part of our national culture and tradition; they are credited with introducing the use of dance as a form of romantic intimacy.

Astaire and Rogers acted and danced together in nine RKO musical comedy films, from 1933 to 1939, and danced a total of 33 partnered dances together on screen.

In my opinion, the best Astaire – Rogers romantic dance scenes are in four of their films – Top Hat, The Gay Divorcee, Roberta, and Follow the Fleet.

Formula for Success

Fred and Ginger’s dance films caused an immediate sensation; audiences were instantly enchanted by the couple’s style, grace, and the use of dance as intimate romance.

The duo’s success was aided by the RKO “screwball comedy” formula, that was popular in the 1930s. These comedies showcase funny satire and spoofing love relationships. They are fast paced, complicated, and with clever twists and mistaken identities—then, add dancing and singing to the mix, and you have a winning formula.

Who wouldn’t be charmed by snappy dialogue, charming plots, lavish sets, opulent wardrobes, award winning composers, gorgeous fashion models, dancing actors, beautiful music, and unforgettable choreography?

Thanks to Fred and Ginger’s multifaceted talent, a new form of romance story danced onto the big screen.

Their dance numbers incorporate:

- Spectacularly entertaining dancing by – Astaire and Rogers

- Beautiful songs by top American composers – Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and George Gershwin

- Unique and challenging dance routines by world renowned dance choreographer Hermes Pan

- Lavish Art Deco set design and high fashion apparel

Along with the screwball comedy format present throughout their movies, many of Fred and Ginger’s dance scenes follow the same dramatic plot line: Astaire attempts to win the affection of the reluctant Rogers. The duo’s subsequent romantic intrigue, flirting, and teasing finally lead up to the ‘big dance number’, where Rogers ultimately gives in to Astaire’s persistent advances.

In fact, Astaire and Pan intentionally choreographed the dance numbers to convey sexual seduction; they highlighted the illusion of symbolic sexual submission by adding in dips and full back bends, and many of Fred and Ginger’s routines end with the two dancers clutching one another passionately as the camera zooms in to capture their aroused expressions. Given Fred and Ginger’s onscreen chemistry, movie audiences could not get enough—they demanded more Astaire- Rogers movies—the pair went on to make 10 films together.

THE DANCERS

Fred Astaire (1899-1987) set the gold standard for stage and film musicals. He was a dancer, singer, choreographer, and actor who starred in 31 musical films, as well as 10 Broadway and West End musicals and 4 television specials in his 76 year long career.

Fred was awarded one Oscar nomination, two Golden Globes, two Grammys, two Emmys, and he made the American Film Institute’s top 100 List; the AFI named Fred as “the fifth greatest male star of classic Hollywood cinema”.

Fred started in vaudeville, as a child singer and dancer, and then, beginning in 1917, he moved up to superstar status in Broadway and on the London stage. In 1933, he began his film career with Ginger Rogers at RKO Pictures. In 1939, Fred left RKO to seek out new opportunities and partnerships on stage, TV, and film.

Astaire was a disciplined perfectionist, and his risk taking dancing was unique, elegant, and innovative. He continued to be a prolific performer for the rest of his life and is credited by numerous movie critics as “the most influential dancer in the history of film.”

Ginger Rogers (1911-1995) was known for her professionalism, acting ability, and dance skill. This talented dancer, singer, and actress starred in 73 films, along with Broadway musicals and radio and television programs.

Throughout her career, Rodgers won numerous awards and honors, including her 1941 receipt of an Academy Award for Best Actress for her leading role in Kitty Fang, and was ranked number 14 on the American Film Institute’s 100 years 100 Stars list. Even given all these accolades, Rogers is best remembered for her enchanting dance partnership with Fred Astaire.

Like Astaire, Ginger began her entertainment career during her childhood; after she won a Charleston dance contest at age 14, Rogers became a successful vaudeville singer and dancer. In 1930, Rogers began to land parts in Broadway productions, including Top Hat and Girl Crazy, and won recognition for her performances, which led to her work in the film industry. Ginger’s first film breakthrough came in 1933, when she was cast as a supporting actress and dancer in the hit 42nd Street musical movie.

During her nine RKO films with Astaire, Ginger performed 33 partnered dances and was able to seamlessly weave these dance scenes into the films’ plot; she never forgot to keep acting when the dance ended. Ginger’s winning combination of dance ability and acting skills made every woman dream of dancing with Fred Astaire. She was box office gold. In fact, Fred paid Ginger high tribute when he claimed that, “Rogers deserves all the credit for our success.”

Over her long career, Astaire, her directors, her choreographers, and even her critics, praised Rogers for her well rounded singing, dancing, and acting abilities. She remains an American icon.

When Ginger Met Fred

Rogers met Astaire in 1930, when she was chosen to star on Broadway in Girl Crazy; Fred was called in to help the dancers with their choreography. At the time, Fred was 30 and Ginger was 19—but neither had any idea that they would soon become the most famous dance partners in history.

Four years after their initial meeting, Fred and Ginger were cast together in an RKO musical, Flying Down to Rio. The pair’s onscreen chemistry was immediately palpable. The film became a box office success and led to their ongoing screen partnership. They went on to star in nine RKO films together and would have likely done more if the 1930s depression hadn’t taken RKO to the brink of bankruptcy by the end of the decade. The studio could no longer afford the big budget musicals with their lavish sets and costumes. In 1949, the pair did reunite in an MGM musical called The Barkleys of Broadway, which was their only film together shot in technicolor.

Astaire and Rogers went on to have very successful and long performance careers, yet their dance partnership remains their most memorable body of work.

Hermes Pan (1909-1990), was an American dancer and choreographer who is best remembered for his collaboration with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

In his mid-teens, Pan started dancing in amateur productions and speakeasies. He landed his first paying dance gig as a chorus boy in a Broadway production of Animal Crackers when he was 19 years old.

Pan moved to California in 1930. He met Ginger Rodgers when he was cast as a chorus singer in the Broadway musical Top Speed. In 1933, Pan was working as an assistant to the dance director, Dave Gould, on Flying Down to Rio. Astaire was on set to help the dancers with their choreography. As Fred was working on steps for a number titled “The Carioca”, he was told by someone that Pan had a few ideas. Astaire invited the dancer to show him what he had in mind, and Fred liked Pan’s suggestions. From that moment on, Fred and Hermes began professional collaboration and friendship that lasted their lifetime.

Pan collaborated with Astaire on 17 of 31 musical films, including every RKO picture Astaire starred in, and three of Fred’s four TV specials. The Astaire-Pan choreographic partnership is credited with being the most influential and revolutionary force in dance choreography of the 20th century film and television musicals. The pair incorporated sweeping long shots, great music, intense practice, and award winning songs and dances that were integral to each films’ plotline.

Beyond working with Astaire, Pan was a much sought after choreographer throughout Hollywood’s Golden Age of musicals. As a dancer and choreographer, Pan had a knack for creating the most appealing dance lines to show off the human body in movement, he changed dancing to take camera angels into account, and he changed the way audiences watched dance.

Pan’s spectacular dance choreography exists in 89 films. He was nominated for Academy Awards for the “Top Hat” and “Piccolino”, two numbers from Top Hat (1935), and for “The Bojangles of Harlem” number in Swing Time (1936). He won an Oscar for Best Dance Direction for A Damsel in Distress (1937), where Joan Fontaine was dancing with Fred Astaire, and won an Emmy for his dance direction in the 1961 television special An Evening with Fred. Pan also received a National Film Award in 1980, and in 1986, the Joffrey Ballet awarded him for his contributions to American dance.

THE MUSIC

RKO sought the leading songwriters on Broadway to score their movies.

Irving Berlin (1888-1989), nicknamed ‘Mr. American Music’, was considered the greatest songwriter in American history; he composed 1,250 songs, and produced 20 Broadway musicals as well as the music for 15 films. Berlin had 25 #1 hits and wrote music for the Astaire-Rogers films Top Hat-1935, Follow the Fleet-1936, and Carefree-1938.

Cole Porter (1891-1964), composed a great part of the American Songbook, totaling 1,200 songs for Broadway and Hollywood musicals, including several Fred Astaire films. “Night and Day”, was composed by Porter for Fred Astaire in the 1932 musical Gay Divorce. Astaire’s version of the song in The Gay Divorcee 1934 film reached number one for 10 weeks on the Your Hit Parade.

George Gershwin (1898-1937), composed hundreds of songs, and worked on 18 Broadway musicals as well as five film musicals. He wrote music for the Astaire-Rogers films Shall We Dance (1937) and The Barclays of Broadway (1949).

Jerome Kern (1885-1945), composed 700 songs, 100 of which were used in stage works. His music was used in the Astaire-Rogers film Roberta (1935).

THE GAY DIVORCEE

In 1934, RKO produced a film version of the Broadway musical The Gay Divorcee that was a box office success.

Directed by Mark Sandwich and choreographed by Hermes Pan, this romantic comedy stared Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Alice Brady, Edward Horton, Erik Rhodes, Eric Blore, William Austin, Charles Coleman, Lilian Miles, and Betty Grable.

The film was awarded an Oscar for Best Original Song for “The Continental”—this number included a 17.5 minute Fred and Ginger dance sequence that wowed audiences, and the movie also landed nominations in 1934 for Best Picture, Art Direction, Music Score, and Sound Direction.

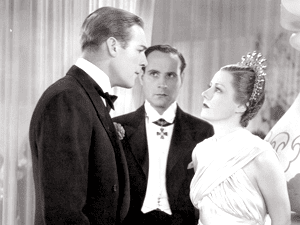

The plot of The Gay Divorcee utilizes screwball situational comedy and mistaken identity. Astaire plays Guy Holden, an American dancer, who falls in love with Mimi Glossop (Rogers), a wife seeking a divorce from her absentee husband whom she has not seen in a few years. When the pair first meet on a London dock, Mimi avoids Guy’s advances, but the love-struck Guy follows her.

After being prompted by her aunt, Mimi consults a London lawyer who advises that she fake an illicit affair as a means of bringing about the grounds for her divorce to be granted. The lawyer has arranged for Mimi to spend the night in a hotel and has hired a co-respondent, Rodolfo, to act as her sham lover. However, Guy checks into the hotel before Rodolfo arrives, and Mimi mistakes Guy as the hired actor who is to play her lover.

This case of mistaken identity leads to funny complications—Rodolfo arrives, the truth about the two men’s identity is exposed, and he then holds the pair hostage in Mimi’s hotel room to ensure that the affair plan will continue. Mimi and Guy plan an escape and spend the night dancing together. The next morning, Mimi’s husband, Cyril, arrives at her hotel room door. Guy hides in the next room as Mimi and Rodolfo pretend to be lovers, but Cyril’s not buying their act; so, Guy then tries to convince Cyril that he and Mimi are the actual lovers—but still, Cyril refuses to believe them. Finally, thanks to the hotel waiter, facts comes to light which show that Cyril himself is an adulterer, so Mimi has her grounds for divorce.

“NIGHT AND DAY” DANCE NUMBER

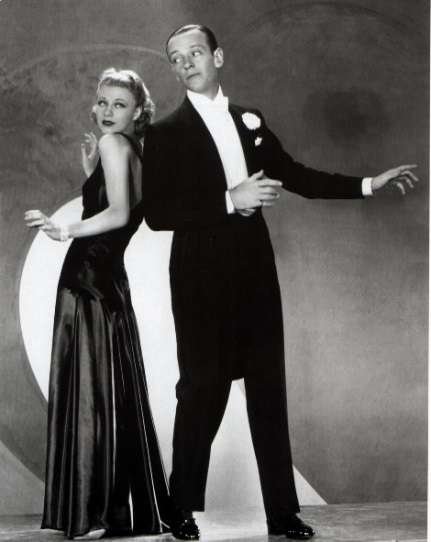

During their great escape from Rodolfo, Fred and Ginger dance a tap and ballroom duet to “Night and Day”. The number established the Astaire-Rogers ‘look’: Fred is dressed in a tuxedo with a white tie and tails, and Ginger has on a lovely, flowing, high fashion gown. The scene takes place in the hotel where the couple has the open air room to themselves, complete with a romantic view of the ocean and beach outside.

Fred admits to thinking of Ginger “night and day” and begins to sing his feelings to her. At first, she repeatedly tries to avoid his advances, but due to his dogged sincerity, amorous claims, and captivating dancing, Ginger begins to be intermittently wooed by his pleas. In this elegant game of cat and mouse, eventually, Ginger begrudgingly submits to dancing with Fred, and even though she tries to escape the room a few times throughout the number, he is successful in preventing her and never breaks from his persuasive dancing. We begin to see Ginger’s mood change—as if she is struggling with her reason, which is telling her to leave, and her emotion, which is telling her to let herself love again—and there are moments where she lets herself dance with Fred with as much feeling as he has.

As the number progresses, and Fred spins Ginger again and again, dipping her, twirling her, dancing side by side with her, pivoting with her, and alternating between holding her close, then rolling her out to arm’s length, we begin to see her attraction to Fred mount. At one point, she even allows herself to be pressed against Fred, cheek to cheek; as he spins and sways, the music crescendos. At the end of the number, Fred slowly dips Ginger, near a padded bench, and we see her place a hand to steady herself as she gazes deep into Fred’s eyes.

Breathless, speechless, Ginger melts onto the bench, and looks utterly overcome by what just occurred. She can only shake her head no when Astaire, seemingly innocently, asks, “Cigarette?”

There is no doubt that this line of dialogue was intended to liken the pair’s dancing to a mind-blowing romantic romp between the sheets for the duo. Audiences are left just as spellbound by the chemistry between Astaire and Rogers as they are by their incredible dancing. This palpable dynamic between the two actors was a major component of their box office success.

ROBERTA

In 1935, RKO released the third romantic musical comedy featuring Fred and Ginger, an adaption of the 1933 Broadway musical that had been based on a novel entitled Gowns for Roberta. The film was another big hit with box office sales netting a profit of over three-quarters of a million dollars.

Directed by William Seiter and choreographed by Hermes Pan, the cast included Irene Dunne, Randolph Scott, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Helen Westley, Clare Dodd, Victor Varconi, Luis Alberni, Ferdinand Munier, and Torben Meyer. Fun fact: Lucille Ball also appeared (uncredited and with platinum blonde hair) in Roberta as one of the fashion models.

Jerome Kern wrote the musical scores for the film, and Max Steiner conducted. Two songs from the movie became #1 hits in 1935, and one of them, “I Won’t Dance,” was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Song.

The film is set in a Paris high fashion salon, complete with fashion shows and Art Deco design. It utilizes complicated romance scenarios and some mistaken identity. Randolph Scott and Irene Dunne are the central romance characters, John and Stephanie. John is a former American football star who goes to Paris with Fred’s character, Huck, a band leader and dancer, because Huck’s band has been booked at a venue. However, when the pair arrives, there is a misunderstanding about the band’s name that prevents Huck’s band from performing at that club. John then seeks help from his aunt who runs a high-end dress salon in Paris.

While at the salon, John meets Stephanie (Irene Dunne), a Russian émigré princess who has now become a dress designer, and is instantly smitten by her, while Huck runs into a customer who turns out to be his previous sweetheart from Indiana, Lizzie, who is masquerading as “Countess Scharwenka” to get work as a singer. The “Countess” lands Huck and his band an engagement at the nightclub where she sings at, and Huck agrees not to disclose her real identity.

Throughout the film, a number of snafus and plot twists occur—John is dismayed that a Russian prince, turned doorman, also seems interested in Stephanie, and he frets over the memory of Sophie, his snobbish girlfriend back in the states whom he left on bad terms. Then, John’s aunt passes away without a will—thus, he inherits the fashion salon that was intended for Stephanie to run, and knows nothing about the fashion trade; so, he convinces her to stay and be his partner. Meanwhile, Huck begins to make odd statements to the press about John’s (non-existent) upcoming innovations in style.

Hearing of John’s success, Sophie shows up at Roberta’s but doesn’t like any of the gowns presented to her. Finally, Huck offers her a dress that John had discarded as too vulgar—she likes the gown, so Stephanie sells it to Sophie, but John is outraged and another quarrel ensues; the result of which is that Stephanie quits the shop with a fashion show a week away. Huck takes over the designs, but that produces disastrous results. Finally, Stephanie takes pity of the pair and returns to save Roberta’s reputation. The fashion show is a success as is Huck and Lizzie’s performing.

Despite a few mistaken assumptions John makes after the fashion show when he overhears Stephanie mention that she and the prince will be leaving Paris, the movie ends with two happy couples—John and Stephanie clear the air about the prince (her cousin), and Huck and Lizzie decide to get married and celebrate with a final tap number. Roberta offers audiences an entertaining plot that nods at Shakespeare’s enduring sentiment: “All’s well that ends well.”

“SMOKE GETS IN YOUR EYES” DANCE NUMBER

As to the dancing in the film, the romantic dance by Astaire and Rogers is “Lovely to Look At – Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” by Jerome Kern. The scene is set in a fashion show in the art deco salon with an orchestra. Astaire is already on screen, conducting the band, dressed in his classic black tuxedo, with white tie and tails, as Rogers enters the ballroom wearing a floor-length black gown that flows around her like silk. She is also wrapped in an exceptional evening coat, of the same silky sheen, that has a high-fashion fur accented waistline, sleeves, and high-collar. Right after Fred removes Ginger’s coat, the couple begins a brief singing duet, followed by their delightful and elegant dance number.

As they sing, they begin to walk arm in arm, moving in tandem. When Fred finishes his final lyrical line, the couple is at the top of a low staircase that leads down to the ballroom floor. As they descend, their movements progress to a more syncopated stroll, which becomes subsequently more and more obviously a dance routine. Fred guides the pair to the center of the dancefloor and then smoothly slides away from Ginger just enough to begin a side by side segment which playfully glides around the dance floor. The magnetism of their partnership is palpable, even though the couple is not touching at this point in the routine. After a few measures of cleverly, mirrored movements, Fred and Ginger’s hands touch for the briefest moment. This prolonged distance between them, accentuated by their expertly synchronous movements, increases the allure of this dance number.

Throughout the piece, Ginger and Fred delight audiences with their flowing dance moves, numerous turns, alternating slow and quick movements, and clever side by side choreography that considers how to best present the dance for the film’s audience.

Just over halfway through the number, Fred takes Ginger in his arms, spinning her in pivots, then stopping on a dime, with their couple’s faces close enough to share a kiss. He dances Ginger this way and that, crisscrossing the ballroom floor, before finally leading her into a prolonged spin in place that is one of the most picturesque moments of the dance as Ginger leans away in an incredibly deep back bend, and her dress flows around her.

After four spins in that position, a length of time that must have made Ginger dizzy given her deep backbend, Fred spins her out into another turn to return to their side by side position, and without missing a beat, or belying any dizziness, Ginger and Fred break out into a difficult tap section of the choreography—as the music crescendos—complete with tandem syncopated turns, spinning leaps, mid-air leg beats, kicks, direction checks, and multiple spins in a row, a frenetic final spinout, and a gravity defying dip—and then, the bombastic music slows once more.

As Fred brings Ginger slowly out of her floor level dip, the couple enjoys a few measures of a romantic embrace; Ginger’s head rests on Fred’s shoulder, and his left arm is around her, as the dancers stroll into the next tandem section. Their precision is perfectly matched.

After this romantic interlude, the pair begins another playful tap section which culminates in a backwards tandem leap up four stairs—which they, of course, make look effortless. After another few turns, which bring the couple up onto the elevated platform where the orchestra is, Fred offers Ginger his arm and they stroll off stage right while gazing at each other.

We viewers are left marveling at Ginger and Fred’s dance capabilities—it’s incredible just how blessed they are to make dancing look both elegant and effortless at the same time.

Other notable dance numbers in the film are: “Let’s Begin”, “I’ll Be Hard to Handle”, “I Won’t Dance” (perhaps Astaire’s best tap dance on film), “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” (reprise), and the “Finale Dance”.

Once again, in Roberta, Fred and Ginger delight audiences with their onscreen chemistry, through dancing, acting, and singing, as well as their overall performance expertise. With this third film together, the couple continued to prove themselves as consummate entertainers as well as RKO box office gold.

TOP HAT

This popular ‘screwball’ musical comedy was produced by RKO in 1935; as the most successful film that Astaire and Rogers made together, it achieved second place in worldwide box-office receipts that year and was RKO’s most lucrative film of the 1930s.

Directed by Mark Sandrich, choreographed, by Hermes Pan, with music by Irving Berlin, the cast included: Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Edward Horton, Erik Rhodes, Eric Blore, and Helen Broderick. Among other notable actors with bit parts, Lucille Ball appears in the film as a flower shop clerk.

At the 1935 Academy Awards, Top Hat was nominated for Best Picture, Art Direction, Original Song (“Cheek to Cheek”), and Dance Direction (“Piccolino and “Top Hat”). In 1990, Top Hat was selected, for its cultural, historical, and/or aesthetic significance, as one of the classic films that the Library of Congress chose to be preserved in the United States National Film Registry. In addition, in 2006, the American Film Institute examined the top musicals in American Film, and Top Hat came in on at number 15 out of 25 on the AFI’S Greatest Movie Musicals list. The film remains the best known work by Astaire and Rogers.

Fred plays an American dancer, Jerry, who is in London to star in a musical show produced by his best friend, a man named Horace. Astaire, who is staying in Horace’s hotel suite, practices a tap number one evening and unknowingly disturbs the hotel guest staying below Horace’s room. Thus, we meet Dale (Rogers) who rings the bell to complain about the noise.

A complicated case of mistaken identity and situational comedy ensues, with the expected plot twists and unlikely surprises of the screwball genre.

Jerry immediately falls in love with Dale and attempts to woo her; reluctant at first, Dale soon begins to find herself attracted to Jerry, but she still doesn’t quite know who he is—which leaves the door open for a colossal misunderstanding to occur.

Due to a misguided gesture and announcement from a hotel clerk, Dale mistakenly believes that Jerry is Horace, the husband of her friend, Madge, and assumes that he is a cheating cad. Meanwhile, Horace merely assumes that Jerry and Dale are having an affair, but since he wants to ensure that Jerry does not become too distracted for opening night, Horace assigns his butler to spy on the couple. Neither Madge nor Horace are aware of the case of mistaken identity.

When Dale confesses all to Madge, who assumes that Horace is having another affair, she turns out to be delighted at the news, given that Horace showers her with consolation gifts whenever he strays.

Finally, when Madge, unaware that Dale and Jerry had already met under mistaken assumption that Jerry was Horace—introduces the pair to each other, she tells them, “You two run along and dance, and don’t give me another thought.” This leads Dale to believe that Madge is giving her blessing on the “affair,” so a somewhat conflicted and guilt-ridden Dale battles with her emotions on the dance floor as Jerry once again attempts to seduce her with the number “Cheek to Cheek.”

While other dance numbers in the film, like “Isn’t It a Lovely Day” and “Top Hat White Tie and Tails,” are worthy of note, “Cheek to Cheek” is a dynamic showstopper and remains one of Astaire and Roger’s most loved dance numbers to this day.

“CHEEK TO CHEEK” DANCE NUMBER

Amazingly, Berlin wrote “Cheek to Cheek” in one day, and “at 72 measures, it is the longest song he ever wrote”. The iconic classic became an instant hit, remaining a timeless and much beloved number to this day.

The choreography of “Cheek to Cheek” is a combination of partnered ballroom dance and side by side tap sequences which reflect the couple’s complicated emotional scenario. Dale feels deceived and guilty, because she thinks that she is being wooed by and is falling in love with Madge’s cheating husband, and Jerry is trying desperately to understand why Dale has such misgivings about him. He sings and dances this number with the sole purpose of inspiring Dale to fall in love with him and to surrender to her feelings. The numerous backbends in the choreography serve to illustrate this surrender theme—repeatedly, Astaire spins, then dips Rogers, guiding her into progressively deeper backbends throughout the number, moves which symbolically urge Roger’s character to submit to her feelings for Jerry.

The first section of the dance is conversational, romantic, and gentle—the couple is in a loose ballroom hold, smoothly turning and two-stepping along with the other dancers on the floor.

By the first instrumental section, the camera pans out to show Fred dancing Ginger across a lavish, Art Deco bridge, and onto an empty ballroom. Here, the couple first separates, to mirror one another for a few measures, and then reconnects in ballroom hold. We witness Ginger’s first and second of her many sweeping backbends.

Next, Fred and Ginger share a lovely, side by side tap sequence, beautifully syncopated with the melody of the tune, which culminates in a triple turn by Rogers, after which Fred offers her his arm, and they stroll for a few four beats, side by side, until Astaire spins Rogers into another triple spin, and then leads her into her third backbend of the number.

This sequence is followed by a second playful tap sequence which Astaire and Rogers dance side by side; this section of the number symbolizes how the couple has literally and figuratively gotten into synch with each other. As the music perks up, so does the dancing—as ever, the Rogers-Astaire partnership makes every move look effortless, light, and elegant—and when Astaire rolls Ginger in, then leads her into a jumping pivot turn as a couple, he deftly ends with guiding her into a dip—her fourth backbend. Fred gently brings Ginger up from the dip, spins the couple back across the dance floor, and then repeats the previous segment, ending with Ginger’s fifth backbend.

Here, the music becomes bombastic for a bit; therefore, the choreography has Fred and Ginger doing running leaps and side by side turns as they hit dramatic lines and use the entire ballroom. This section is followed by a sweet interlude, where the melody reenters, and the couple’s movements slow, becoming more intimate and romantic, and then Fred spins himself into Rogers’ side.

Next, as the choreography intermittently incorporates spins, pivots, and side by side work, we hear the music building towards another crescendo—here, Astaire and Rogers let loose. They leap, turn, kick, and backwards run, then spin, and towards the camera.

The finale of the number incorporates three stellar ballroom lifts in a row—Astaire spins and vaults Rogers into one lift after another; her feathered dress (a pet peeve of Astaire’s due to its tendency to shed) flows in waves of fabric and feathers as she glides through the air with gravity defying grace.

Directly following third lifts, Astaire leads Rogers into her deepest back bend yet—the music stops, for four beats—here, Dale appears to surrender to Jerry completely. After the pause, Jerry ever so slowly brings Dale out of the backbend and spins her into an embrace for the couple’s final iconic ‘cheek to cheek’ section of the number.

For a few romantic moments, the couple rests against a wall, and Dale seems as completely smitten with Jerry as he is with her. After a few measures gazing into each other’s eyes, Jerry moves closer to Dale, and we think that they might kiss—but, alas—they don’t (at least not yet).

Truly, it’s easy to see why “Cheek to Cheek” remains a sensation and Astaire and Roger’s most remembered number—it epitomizes class, grace, and romance.

FOLLOW THE FLEET

In 1936, RKO produced the fifth Astaire-Rogers romantic musical comedy. Follow the Fleet was directed by Mark Sandrich, choreographed by Hermes Pan, and was scored by Irving Berlin. It was the 14th most popular film at the British box office in 1935-36.

The cast included: Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Randolph Scott, Harriet Hilliard, Astrid Allywyn, Betty Grable, Harry Beresford, Russell Hicks, Brooks Benedict, Ray Mayer, Lucille Ball, Tony Martin, Jane Hamilton, and Doris Lloyd.

The film was quite successful at the box office, and while netting profits that were slightly less than Top Hat, it still ranked as one of RKO’s top movies of the decade.

In 2006, the American Film Institute nominated Follow the Fleet to be included in its AFI’s Greatest Movie Musicals list, and while it did not make the final list, which only included the top 25 films, it ranked 49th out of the 180 AFI nominated films.

In the film, Fred and Ginger play former dance partners who meet again at a nightclub, called Paradise, where Rogers’ character, Sherry, is working as an entertainer and dance hostess. Astaire’s character, Seamen “Bake” Baker, is a Navy man who, along with his crewmates, is awarded shore leave one night. The group of seamen head off to the Paradise, in hopes of meeting young ladies, and spend the night flirting, drinking, and dancing.

Bake and his buddy, Bilge (Randolph Scott) both find romance that night. Bake reunites with Sherry, assumes that they will reinstate their dance partnership, and insists that she propose to him since she once turned him down. Later, the couple enters and wins a dance contest, but Bake eventually costs Sherry her job when he pretends to be her manager and complains about her working conditions.

Bilge originally ignores, and then falls for Sherry’s sister, Connie (Harriet Hilliard) after she is dolled up by some of the show girls. Bilge suggests that Connie and he find a ‘quieter place’, and they head back to her apartment. While there, Bilge raids her icebox and makes moves on Connie; he seems very interested in her and the ship she inherited from her deceased father. Earlier in the evening, Bilge tells Connie that they will have a ‘hot date’ the next time Bilge is on shore leave, but he is frightened off when she mentions the word ‘husband.” He uses the excuse of getting back to the ship before their curfew ends and leaves Connie’s, only to get involved with Iris, a rich divorcee, who prefers a dalliance to marriage—that noncommittal affair suits Bilge just fine.

After costing Sherry her job, Bake promises to make it up to her by trying to get her an audition with a local talent agent he knows, and he intends to set that meeting up for the next day. However, the fleet is called out on a mission that very night. Both Shery and Connie are upset by the news.

Connie, who has fallen in love with Bilge, meets the man who oversees their deceased father’s ship because she wants to fix it up for Bilge to captain one day—she is unaware that Bilge has commitment issues or that he has already moved on to romancing Iris.

Sherry is furious with Bake for causing her job loss, promising to score her an audition, and then appearing to bail, and she wants to prove to him and herself that she can land that audition all on her own—which she does.

Meanwhile, Connie has used up her savings and the company’s credit to fix up her father’s ship. She intended for Bilge to captain it and to sail around with him as husband and wife.

When the fleet returns, unbeknownst to Connie, Bilge prepares for a date with the widow; he stands Connie up. Bake attempts to call Sherry to make things up to her, but she is ignoring his calls. He spends all night in the phone booth waiting for her call.

Sherry ends up scoring an audition with the talent agent, and she’s about to be offered a contract after her stellar dance performance; she is preparing to sing a song next. Ironically, that’s when Bake shows up at the talent office and overhears that some lucky lady is about to be offered a contract.

Bake mistakenly assumes that the woman being offered a position is a rival for the opening that he wanted to get Sherry, so when the assistant isn’t looking, Bake puts sodium bicarbonate in the drinking water for this “mystery rival,” thinking that he is removing Sherry’s competition, but he ends up ruining Sherry’s audition because she is sick to her stomach after drinking the water and cannot finish her song.

Many of these foibles come to light at the widow’s party; Sherry finds out that Bake sabotaged her audition, and she get revenge on Bake, while Connie finds out why Bilge stood her up—she catches him romancing Iris.

Sherry has lost her job and the audition, and Connie feels the Bilge has played her for a fool and intends to leave town; however, fixing up her father’s ship has cost the stewardship company so much money that Captain Hickey will likely lose his job, and Connie will lose the ship, if they don’t come up with $700 as soon as possible.

Bake comes up with a plan to set both Sherry’s job prospects and Connie’s finances to rights; he calls in a favor for the set, enlists the Navy band, and plans to put on a fund raising musical show on the deck of Connie’s ship. Also, to help Connie out, Bake casts Iris in his show, goes to her home to rehearse, and plans a ruse where Bilge will walk in and think that he is having an affair with Iris—though the two are just rehearsing a scene for the show. The plan works, and Bilge storms off.

The night of the performance, Bake is not granted shore leave, so he jumps ship to be there, not wanting to let Connie down. Bilge and other crewmen are tasked with going to shore, finding, and arresting Bake.

Once on the ship, Bilge runs into Connie and seems to want to rekindle their romance; she tells him that ship has sailed. Bilge finds Bake and intends to arrest him, until Bake tells him the predicament that Sherry and Connie are in, and how Connie fixed up the ship for Bilge. Bilge decides to allow Bake to finish to show and agrees to stall the other crewman.

It turns out that Mr. Nolan, the talent scout that Sherry auditioned with, attends the show. He’s impressed, and he offers Bake and Sherry a show on Broadway; Bake says he will accept on the condition that Sherry propose to him—which she does. Connie and Bilge also kiss and make up. The movie ends with Bilge taking Bake back to the ship to serve his time in the brig for going A.W.O.L, and the two couples waving at each other from shore and ship.

This screwball romance is complete with snappy dialogue, mistaken identity, comedic scenes, excellent dancing and singing, and a happy ending for all. It’s easy to see why RKO enjoyed success after success cashing in on the Astaire-Rogers partnership.

As for the dancing in Follow the Fleet, two notable dances within the film are “Let Yourself Go” and “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket”.

“LET’S FACE THE MUSIC AND DANCE” DANCE NUMBER

The most impressive Astaire-Rogers dance number in the movie, a Broadway and Ballroom duet, is done to Irving Berlin’s song “Let’s Face the Music and Dance.” Some consider this their best dance. The number is danced as part of the benefit show on Connie’s ship. The set is a lavish Art Deco design with fashion models in high gowns walking across the scene. This dance number, as part of a ‘play within a play’, is different than other Astaire- Rogers’ dances in that it steps out of the plot and is a stand-alone dance scene on its on merits.

The scene opens with Fred, in his classic tux and tails, looking lonely—everyone snubs him. He seems to be invisible to the various high class socialites who cross the stage. Eventually, after rejection after rejection, Fred pulls out a pistol and holds it to his head just as Ginger enters.

She has on a sparkling evening gown with a fur collar. We soon see that all is not well. She is crying and soon gets up on the wall, appearing to want to jump/kill herself. Fred sees her and rushes over to save her—through this act, he seems to have found a purpose to live on.

Roger’s character continues to look distraught as Fred looks at his gun again. Rogers notices, so he gestures that it’s his—as if to say—I was going to end it all too—she moves to grab it, but he doesn’t let her have it—instead he tosses it off screen. Rogers looks even more dejected—so Fred then shows her his empty wallet, (his character had just lost all his money at the gambling table). He shrugs, and she looks defeated as she leans against a wall. Fred tosses his empty wallet off screen too.

It’s after this opening interlude that Fred sings his first lyrics: “There may be trouble ahead, but while there’s music, and moonlight, and love, and romance, let’s face the music and dance.” Ginger seems to listen but moves away. He follows adding another few lines. By the second verse, she is considering his words and mindset. By the third verse, she has allowed Fred to take her arm and guide her towards the center of the floor. Astaire keeps singing, and we see Roger’s character looking miserable; yet, she begins to look wistful too, as if considering the escape his words may offer her. Fred spins in front of her, at first not touching her, and sways his arms as if hypnotizing Rogers into following his movements—which she does.

This goes on for a few more measures—until, finally her character is swayed. She tosses her handkerchief off camera, and the pair dance side by side. The choreography incorporates many changes of place, using both single and double hand holds and roll outs—there are even two one-legged turns where Rogers holds her balance as Fred spins her around.

Pan includes a lot of swishy, side by side moves, and tandem spins—thus creating a dance that appears as if it belongs in a fairytale. As the music builds, the moves sharpen and liven. The number includes more Broadway and Ballroom style moves, than the duos previous tap numbers. At times the choreography is reminiscent of tango patterns when certain crescendos occur—Pan includes multiple pivots and jumps, and powerful movements, such a leaps into leg beats, and back layouts.

The number ends with Fred and Ginger’s characters seeming to have come back to a sense of renewed hope—no matter what life throws at these two people—we’re now convinced that they’ll preserve, and so should we all. Check out their dance here:

Sources:

Film

- Silver Screen Icons: Astaire and Rogers, Warner Bros., DVD collection of Astaire and Rogers RKO musical films

- Youtube videos and documentaries

- Turner Classic Movies – RKO

- BBC documentaries

- biography.com documentaries

- dailymotion.com videos and documentaries

Online Reviews

- Internet Movie Database – IMDB

- Internet Broadway Database

- TCM Movir Database

- AllMovie

- AlsoDances.net

- Wikipedia

- Roger Ebert.com

- Playbill Magazine

- Hollywood’s Golden Age.com

Books

- Astaire Dancing: The Musical Films of Fred Astaire, John Mueller, 1985.

- The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book, Arlene Croce, 1974.

- Fred Astaire: An Illustrated Biography, Michael Freedland, 1976.

- Fred and Ginger: The Astaire- Rogers Partnership, 1934-38. Hannah Hyman, 2007.