Picture this, King Arthur the legendary figure of medieval heroism, gallops nobly through the thick, mysterious mist of Britain. But wait, his noble steed is…a man clapping coconut shell halves together? Welcome to the world of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, where high fantasy collides with low-budget absurdity, and grandeur is gleefully dismantled by silliness.

In this bizarre yet captivating moment, we are thrust into a universe where the epic becomes farcical, the heroic becomes ridiculous, and comedy reigns supreme. It’s a scene so quintessentially Monty Python that it sets the tone for a film brimming with chaotic brilliance. The origins of Monty Python and the Holy Grail lie in the irreverent minds of the Monty Python comedy troupe, a collection of six comic geniuses, Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, who came together in late 1960s Britain. Emerging from their work on the groundbreaking sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus, they quickly established a reputation for skits that were absurd, cerebral, and sometimes outright nonsensical.

By the 1970s, they were itching to move beyond television and disrupt the cinematic scene. The cultural climate of the time was ripe for rebellion; the countercultural movement had paved the way for boundary-pushing art, and audiences were eager for entertainment that thumbed its nose at tradition. The Pythons, with their anarchic humor and relentless drive to challenge norms, were perfectly positioned to deliver. When Holy Grail was released in 1975, it wasn’t just another comedy, it was a hilarious middle finger to the stuffy, conventional storytelling of its times.

Monty Python a Comedy Legend

Monty Python and the Holy Grail isn’t just a movie, it’s a comedic revolution. The film redefined how humor could function in storytelling, marrying historical parody with absurdist skits, meta-commentary, and slapstick genius. Its low-budget charm, complete

with intentionally amateurish effects and sets, became a part of the joke itself, subverting the expectations of what an epic film should look like. Beyond the laughs, Holy Grail is a masterclass in satire.

It gleefully pokes fun at everything from the pomposity of medieval mythology to the futility of bureaucratic systems, all while questioning the very idea of heroic narratives. The film’s nonlinear structure, breaking of the fourth wall, and refusal to take itself seriously set a precedent for future comedy films and television.

Without Holy Grail, we might not have the absurdist landscapes of The Simpsons, South Park, or Rick and Morty. In short, Holy Grail doesn’t just matter because it’s funny, it matters because it proved that comedy could be smart, subversive, and enduringly influential. It’s a coconuts-clapping, grail-hunting, knight-taunting masterpiece that continues to inspire and delight audiences nearly fifty years later.

Absurdity as Art: The Humor and Writing

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a masterclass in comedic variety, blending absurdist gags, slapstick, intellectual wit, and biting satire. Let’s dissect some of its most iconic scenes to understand why they endure. The humor often stems from the nonsensical juxtaposition of modern sensibilities with medieval settings.

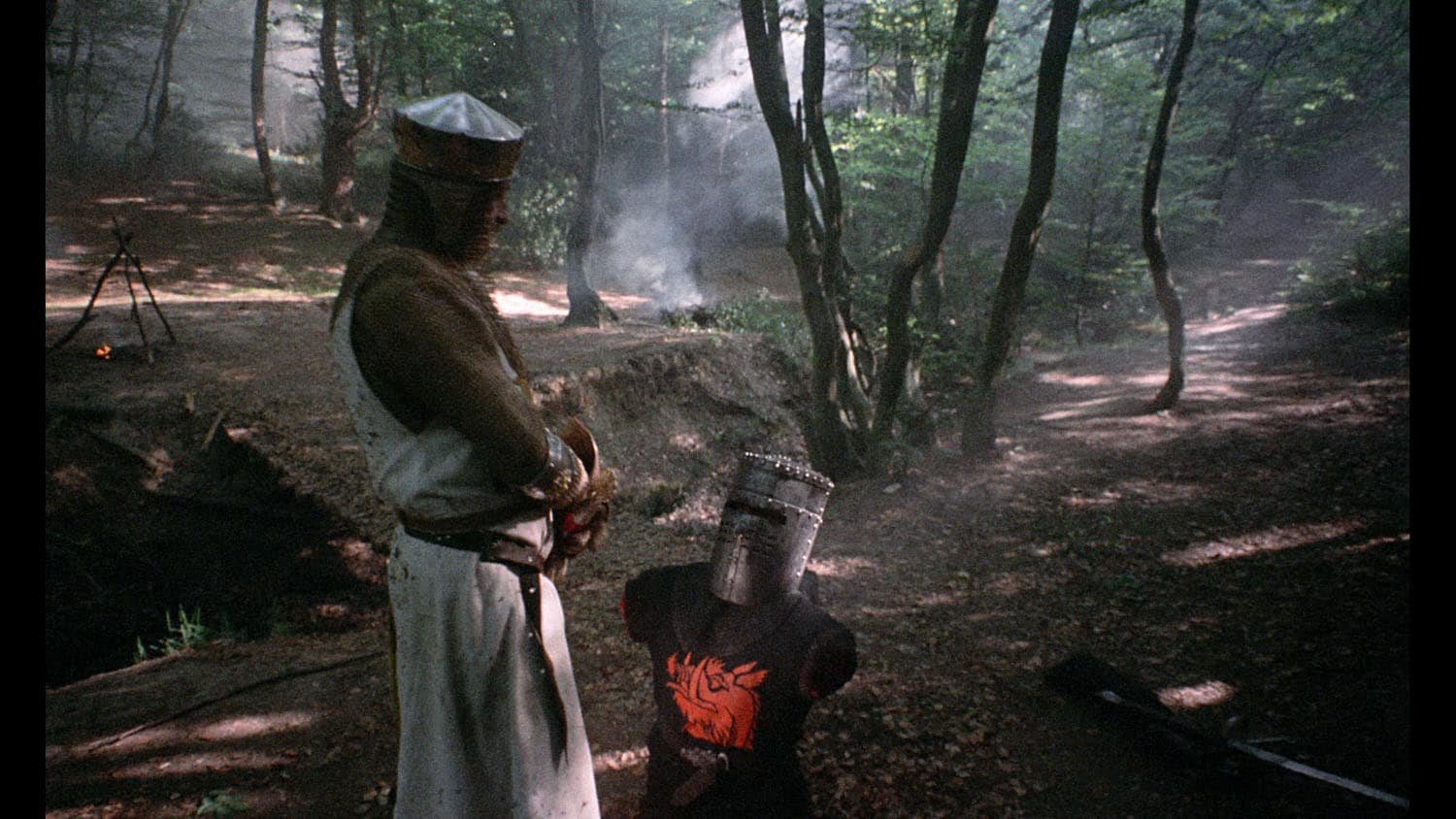

The Black Knight Duel is a prime example: an epic battle reduced to absurdity by the Knight’s unwavering, comically disproportionate bravado. The escalating ridiculousness of the dismemberment parallels the group’s disdain for taking anything seriously, including life-threatening injuries. Physical comedy peppers the film, from the coconuts clapped together to mimic horses to knights inexplicably slapping themselves with fish during mock battles.

The Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog scene elevates slapstick to surreal heights, a fluffy bunny turned into an apex predator is so absurd it demands laughter, yet it’s performed with deadly seriousness by the characters.

The film doesn’t shy away from clever wordplay or philosophical commentary. Consider the anarchist peasants discussing political theory with King Arthur. (“Supreme executive power derives from a mandate from the masses, not from some farcical aquatic ceremony!”) The scene mocks both the futility of feudalism and the overly intellectualized debates of modern politics. The film is a parody of the medieval epic genre, ruthlessly lampooning chivalric ideals and the self-importance of quest narratives. The Knights’ failure to accomplish much of anything pokes fun at the glorified hero archetype, while their interactions with figures like Tim the Enchanter add layers of absurdity to traditional “mentor” tropes.

Monty Python cleverly mocks not just medieval epics but also the societal norms of both medieval and modern times. King Arthur embodies the pompous leader, completely out of touch with the people he claims to rule. His insistence on his divine right to govern contrasts sharply with the peasants’ cynicism. This dynamic satirizes the blind faith in authority figures, both in history and in modernity, highlighting the absurdity of inherited power.

The film dismantles traditional heroic narratives. Arthur is portrayed not as a noble figure but as deluded and bumbling, his “quest” plagued by mundane obstacles like bridge keepers and ill-tempered rodents. This skepticism extends to religion and societal hierarchies, creating a timeless critique of unquestioned power. The film’s dialogue is endlessly quotable, a testament to its sharp writing and universal appeal.

Some of the standout lines include immortalized in pop culture this line captures the blend of slapstick and absurdism. Its enduring appeal lies in the sheer audacity of a character denying the obvious truth, a timeless comedic trope. The French Taunter’s creatively juvenile insults parody the tropes of gallant battles and knightly diplomacy. This bizarre non-sequitur has become a cultural phenomenon, highlighting the film’s commitment to humor that is both surreal and irreverent. The line, from the anarchist peasant, mocks the glorification of revolutions by undercutting the drama with absurdity. It also serves as a meta-commentary on modern political discourse.

The Pythons weren’t just actors, they were shapeshifters of hilarity, donning wigs, fake beards, and sometimes questionable accents to bring their zany world to life. Every member of the group played multiple characters, showcasing their staggering versatility. They blurred the line between performers and caricature artists, each bringing their own flavor of madness to the feast. Graham Chapman as King Arthur, with a regal air undercut by a clueless lack of self-awareness, Chapman’s Arthur is the straight man amidst a carnival of lunatics. His noble proclamations are hilariously undermined by petty squabbles (“Bloody peasant!”) and his inability to see just how ridiculous his quest is. Chapman’s commanding yet oblivious performance anchors the film, making him both the hero and the punchline.

John Cleese as Sir Lancelot, Cleese takes Lancelot’s chivalric bravado and cranks it up to an 11. Whether he’s slaughtering an entire wedding party in the name of gallantry or storming Camelot (“It’s a silly place”), his over-the-top earnestness and wild-eyed intensity steal every scene he’s in. Lancelot is a parody of action heroes long before the term even existed.

Eric Idle as Sir Robin: Cowardice has never been so glorious. Sir Robin is a knight who “nearly fought the Dragon of Angor” but mostly specializes in running away. Idle’s knack for self-deprecating humor is amplified by the minstrels who gleefully sing of his failures, making Sir Robin a hilariously tragic figure. “Bravely bold Sir Robin ran away…” is a tune we’ll never forget. The beauty of Holy Grail lies in its world brimming with absurd side characters who manage to leave an indelible mark, no matter how brief their screen time.

The French Taunters: Led by John Cleese (again!), these cackling, insult-hurling maniacs deliver some of the film’s most iconic lines. Their absurdity is heightened by their commitment to petty cruelty, complete with flying livestock. These arboreal fanatics demand shrubberies with such conviction that they became instant legends. Their nonsensical menace is a masterclass in Python absurdity, forcing Arthur and his knights into a quest within a quest.

Tim the Enchanter: Played with fiery gusto by Cleese, Tim is a wizard with a flair for dramatic pauses and exaggerated hand gestures. His ominous warnings about the Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog, delivered with wild-eyed conviction, are comedy gold. If necessity is the mother of invention, then Holy Grail is its rebellious, coconut-clapping child. Here are some delightful nuggets from the trenches of production.

The budget didn’t allow for actual horses, so the Pythons embraced absurdity and used coconuts to mimic hoofbeats. The resulting gag not only saved money but became one of the film’s most iconic running jokes. The Killer Rabbit, this furry fiend looks harmless until it launches itself at throats with a flurry of teeth and fake blood. The low-budget rabbit puppet was a ridiculous yet perfect way to parody the trope of mythical beasts guarding great treasure.

Improvised Filming Locations: Castles were in short supply, so the same locations were used multiple times, with clever camera angles and set dressing to disguise them. This frugality only added to the film’s scrappy charm. The Cold, Muddy Reality, the actors endured freezing conditions, mud-soaked costumes, and a lack of modern comforts while filming in Scotland. Despite the hardships, they delivered performances so committed that it’s hard to believe they weren’t lounging in Hollywood luxury.

Legacy of the Knights of Comedy

The Pythons didn’t just create a movie, they built a kingdom of comedy that continues to inspire. Whether it’s Chapman’s noble oblivion, Cleese’s manic energy, or Idle’s cowardly charm, their performances are a masterclass in character-driven hilarity. And the supporting cast? Proof that sometimes the loudest laughs come from the smallest roles Monty Python’s Holy Grail is a masterclass in making “less” into “more.” With a production budget of less than $400,000, the film relied on sheer ingenuity to stretch every pound and penny. Horses? Too expensive. Coconut shells clapped together to mimic hoofbeats.

The limitations birthed moments of brilliance that wouldn’t have existed in a larger production, such as the running gag of the knight’s pretending grandeur while inhabiting obviously low-budget spaces.

And then there’s Terry Gilliam’s surreal animations. Gilliam turned scraps of Victorian-era art and magazine cutouts into absurdly whimsical sequences that felt like the fever dream of an unhinged medieval bard. These animated interludes didn’t just save costs; they gave the film a unique visual identity. His animations became an integral part of Python’s DNA, bridging scenes and amplifying the absurdity with impossible, dreamlike visuals. In hindsight, these limitations didn’t detract from the film, they enhanced its scrappy, anarchic charm. Its low-budget feel became a feature, not a bug, adding layers of satire that mocked the often-bloated seriousness of historical epics.

The Holy Grail didn’t just redefine comedy, it rewrote the entire language of parody. Its self-aware humor, absurdist takes on genre tropes, and sharp satirical edge created a blueprint for future comedies. From Airplane! to Shrek, the fingerprints of Monty Python are unmistakable. The film’s legacy also thrives in the stand-up routines, sketch shows, and absurdist films that followed, inspiring comedians like Eddie Izzard, the Simpsons writing team, and countless YouTubers.

Its dialogue, full of nonsensical debates about swallows, anarchic peasants questioning monarchy, and killer rabbits, became timeless memes long before memes existed and have transcended generations, quoted at costume parties, internet forums, and everyday banter. The film’s cult following birthed singalongs, reenactments, and even a Broadway musical, Spamalot, proving that Holy Grail isn’t just a movie, it’s a cultural touchstone.

In a world steeped in meta-humor and absurdist storytelling, Monty Python and the Holy Grail feels more relevant than ever. Today’s audiences, raised on Rick and Morty, BoJack Horseman, and Everything Everywhere All at Once, find a natural connection to Python’s disregard for narrative conventions and its embrace of chaos.

The film’s ability to blend intellectual wit with pure ridiculousness resonates in an era where cultural commentary often walks hand-in-hand with meme culture. Moreover, Holy Grail’s humor holds a mirror to authority, traditions, and societal norms in a way that feels timeless. Whether mocking divine right, the rigidity of organized religion, or the bureaucracy of knights on a quest, the film strikes at ideas that remain ripe for satire in any era.

It thrives on the recognition that even the most epic stories are just one step away from being utterly ridiculous. The film’s lasting resonance lies in its audacious refusal to take itself seriously, its playfulness with narrative and genre, and its timelessly quotable script. Its humor remains a testament to the idea that creativity can triumph over constraints, irreverence can challenge convention, and silliness, when wielded with razor-sharp wit, can be immortal.

Comedy That Stands the Test of Time

Few films achieve the rare alchemy of timelessness and absurdity, but Monty Python and the Holy Grail doesn’t merely achieve it, it revels in it. Nearly fifty years after its release, it remains as uproariously funny and culturally relevant as ever, a testament to the power of creative anarchy and unrestrained wit. What other film could blend slapstick gore, historical parody, philosophical musings, and a ludicrous killer rabbit into something so enduringly brilliant?

This isn’t just a movie, it’s a cultural artifact, etched into the annals of comedy history. From the iconic “It’s just a flesh wound” to the infamous French Taunter, it transcends mere entertainment to become a shared language for comedy lovers, endlessly quoted and referenced by those in the know. For some, it’s a window into British humor, for others, it’s a rallying cry for the joy of the absurd. And let’s not forget its sheer audacity, to take on the legend of King Arthur and turn it into an unhinged farce requires comedic guts, and the Pythons deliver in spades.

Ultimately, Monty Python and the Holy Grail is more than a collection of scenes and sketches, it’s a joyful celebration of the ridiculous. It dares us to laugh at the lofty, poke holes in the sacred, and embrace the chaos. Whether you watch it for the first time or the fiftieth, the laughs are as fresh as ever, proof that true genius, no matter how silly, never fades. And if all else fails, it leaves you with one eternal, unanswerable mystery to ponder: What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow? African or European, the question lingers, a brilliant reminder that even in comedy, sometimes it’s the journey, not the answer, that truly matters