“They Live” — a 1988 masterpiece of sci-fi dystopia, libertarian rebellion, and social satire directed by John Carpenter. It’s campy, gritty, with one of the longest, most unnecessary-yet-glorious fistfights in cinematic history. But beneath the surface, “They Live” is sharp, dripping with social commentary, a perfect marriage of B-movie bravado and pointed critique on exploitation, corruption, media manipulation, and the pursuit of power.

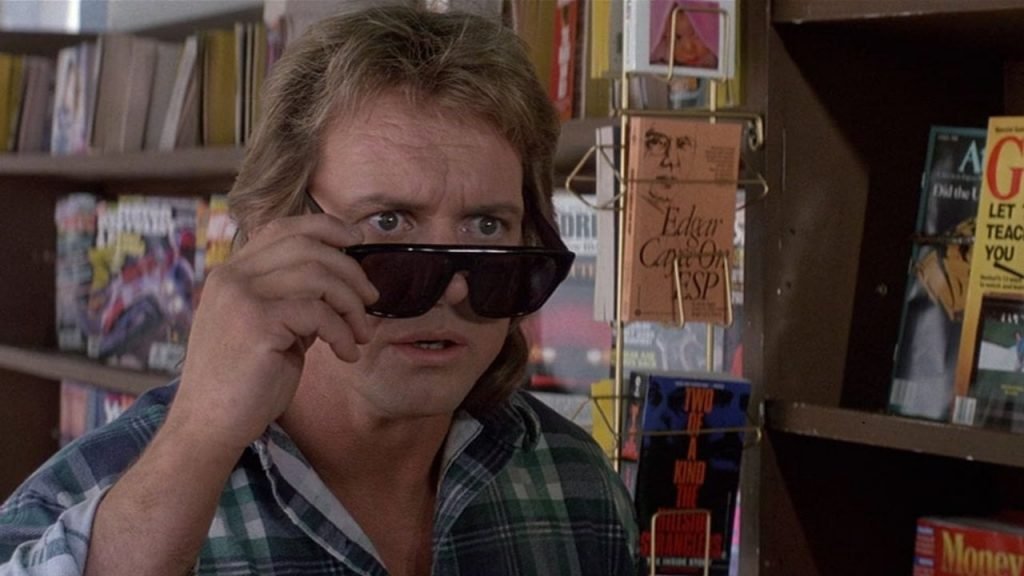

Carpenter satires the illusion that the elites took the American Dream, flipped it on its head, and then bashed it into oblivion with a steel chair. Plot in a nutshell, “They Live” follows “Nada” (played by wrestling legend Roddy Piper), a down-on-his-luck drifter who stumbles upon a pair of special sunglasses. These glasses reveal the hidden reality around him: a world where wealthy aliens control the human race through subliminal messaging and a hypnotic media narrative. Billboards hide messages like “OBEY,” “CONSUME,” “MARRY AND REPRODUCE,” all demanding docility and subservience.

With his new insight into this dystopian world, Nada becomes a one-man resistance, determined to tear down the alien overlords. Carpenter used this sci-fi thriller to take aim at a very real monster, the entrenchment of mass consumerism, exploitation, corruption, and media manipulation in America. The movie hit a nerve at a time when the U.S. middle class was being disenfranchised and unemployed due to globalist policies of outsourcing jobs overseas, the deindustrialization of the U.S. economy, and economic looting by global cartels –all while there was out of control massive investments in stock and debt scams and toxic bubbles that eventually collapsed causing economic crisis and social misery.

The aliens represent the global elites, manipulating the masses and controlling society through a web of consumer culture and mind-numbing media. “They Live”, the cult classic where sci-fi meets a social slap in the face. Carpenter didn’t just deliver a story about aliens; he crafted a relentless critique of the powers that manipulate from behind the glossy veneer.

Nada, armed with those oh-so-revealing shades, gets to see the truth that most are too distracted, too anesthetized, to notice. The aliens, all slick and suited, aren’t just visitors from another planet; they’re stand-ins for the wealthy elite, puppet masters pulling the strings while humans dutifully obey, consume, and reproduce. Through that monochromatic lens, the movie strips away the illusion, showing us a world driven by hidden commands to stay compliant, to keep spending, and to never question the system.

And at the core of this dystopian nightmare is a message that hits hard: society isn’t broken by some outside force, it’s been sold out from the inside, with an invisible government more than happy to keep the rest of us in a daze. Nada’s refusal to stay silent, to let the masses remain oblivious, turns him into a beacon of rebellion. But it’s no fairytale: he’s fighting a battle against a system designed to keep people from waking up. Carpenter’s critique of consumer culture, corruption, and media manipulation isn’t subtle, it’s more like a steel-toed boot to the face of mass behavioral conditioning.

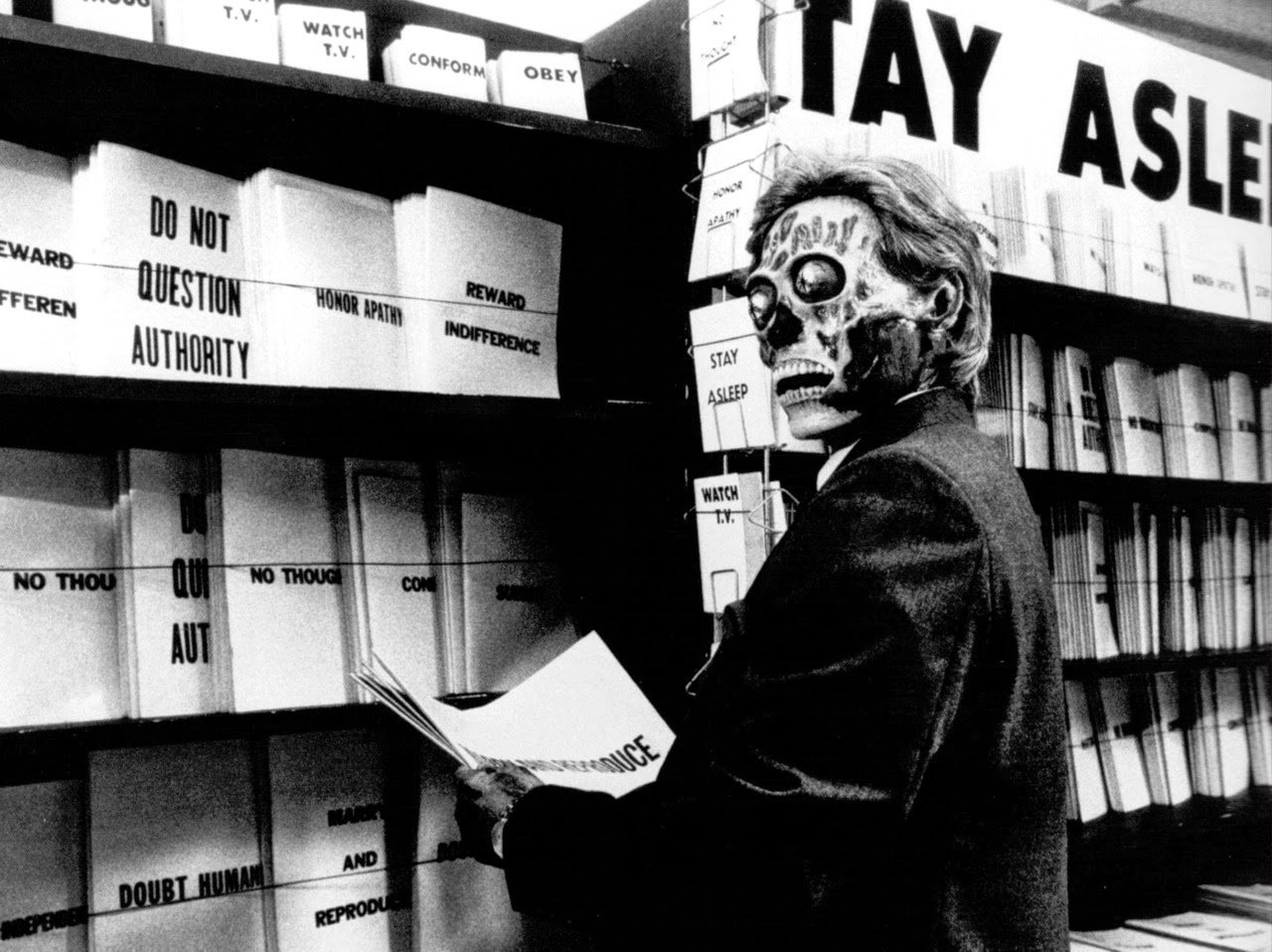

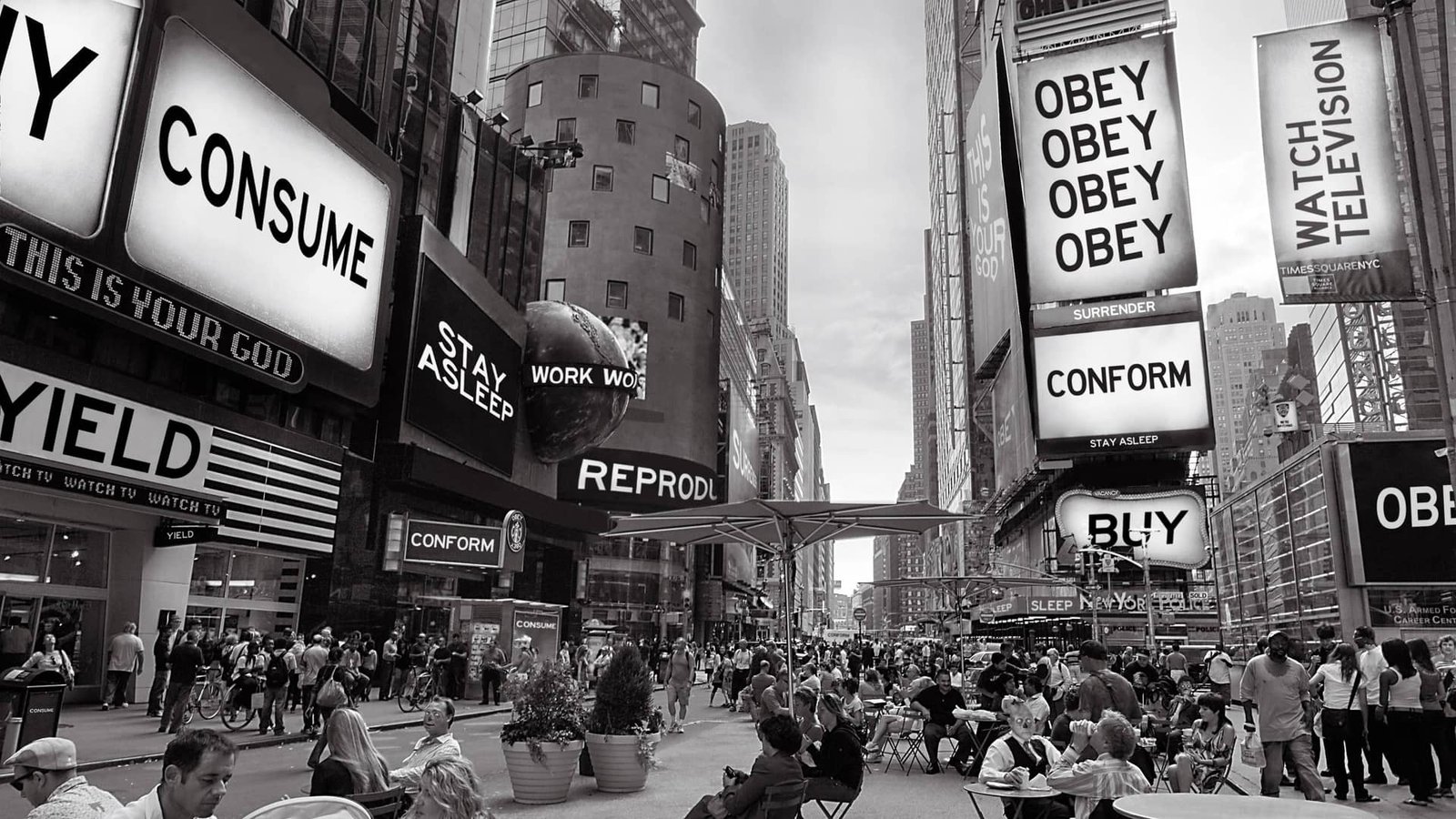

It’s a film that stares straight into the eyes of 1980s America, and hell, its bite is still just as sharp today. Consumerism and Obedience, we see society stripped of pretense. Advertisements, money, and even magazines scream at their readers to conform: “OBEY,” “BUY,” “STAY ASLEEP.” It’s a bleak view of consumerism, where individuals are conditioned to desire and consume rather than think. Carpenter is essentially screaming at us that all this mindless consumption blinds us to reality. We’re taught to buy happiness, success, and status rather than fight for actual freedom or fulfillment.

And in doing so, we’re complicit in our own oppression. John Carpenter’s scathing critique on consumerism and control. “They Live” exposes how society’s pillars, advertising, media, Wallstreet, Madison Avenue, Hollywood, aren’t just passively presenting options; they’re commanding obedience, lulling everyone into a hypnotic stupor of “consume, conform, obey.” Nada’s sunglasses strip away the illusions, revealing messages designed not merely to persuade but to dominate. It’s brutal, really, the way Carpenter suggests we’re not just innocents in this; our insatiable desire to buy into the system, to cling to comfort over autonomy, makes us complicit.

The dystopian magic here is in how Carpenter captures the why behind it all: an artificial happiness, a fabricated self-worth served up in shiny packaging. True freedom? Actual fulfillment? Those are rendered dangerous, subversive even, because they break the cycle, shatter the illusion. This world wants workers, not thinkers, and most would rather stay asleep than risk the discomfort of awareness. In a sense, Carpenter’s “They Live” dares the viewer to shatter their own sunglasses, to see their world without the veneer, to make the terrifying leap from obedient consumer to disobedient free agent. And that, my dear, is exactly why the film remains a razor-sharp critique of modern existence.

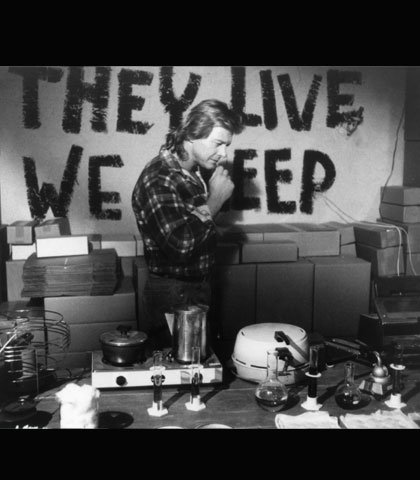

“They Live” Trailer:

GLOBALIST CONSUMERISM AS A TOOL OF CONTROL – in “They Live”, aliens aren’t so much about tentacles and laser guns but control through psychological conditioning. These aliens are the one percent who have the wealth, who run the businesses, and who manipulate every institution. Nada, as a homeless drifter, is a direct contrast to these elites, showcasing the divide between the powerful and the powerless. Carpenter saw this as more than a metaphor — it’s a savage critique of consumerism itself, where wealth and influence enable exploitation.

Here, the aliens don’t lurk in shadows or hover in spaceships; no, they hide in plain sight, thriving under the political-economic machine. Through Nada’s gritty sunglasses, we see the true horror: subliminal messages plastered everywhere, screaming obey, consume, conform, turning the world into a breeding ground for the elite’s unquenchable thirst for control. This society’s real alien invasion isn’t about tentacles or teeth but systematic exploitation and wealth siphoning from the bottom up. It’s almost… poetic, don’t you think?

Nada’s homelessness isn’t incidental; it’s a stark counterpoint to the elites’ sterile, affluent world. He’s the living proof of the divide between the “have-nots” and the “have-way-too-much.” So, the aliens represent not the extraterrestrial but the “one percent” who wield power as a tool to feed the profit monster at the expense of society. The best part? The monster doesn’t need laser beams or invasions, it’s already here, embedded in the system. It’s a masterful setup: Carpenter didn’t create monsters from imagination; he just held up a mirror.

MEDIA AS PROPAGANDA, Carpenter digs deep into how the media lulls us into a submissive trance. Television broadcasts are filled with content designed to entertain or distract rather than inform. News stories downplay economic exploitation while hyping up inconsequential issues, a vision of media manipulation that’s painfully relevant even now. TV screens, with their hidden “OBEY” messages, remind us of how the media often shapes narratives essentially sedating the masses with mindless entertainment while ignoring the real battles at hand.

Carpenter’s critique is like a sharp knife, isn’t it? He slices through the glittering fabric of mass media, exposing its real function: a tool for control, wielded as smoothly as a dagger by those in power. Under his lens, every news story, every feel-good drama, every repetitive sitcom, is an anesthetic drip, injected to keep the public pacified, compliant, blissfully ignorant. The more they consume, the more they drift into a comfortable, disconnected haze.

Carpenter’s “OBEY” messages aren’t just cryptic, they’re sinister and profound; they show how propaganda isn’t just overt lies but can be found in the subtle, insidious reinforcement of existing hierarchies.

So, while the people binge-watch and scroll endlessly, they unknowingly submit to the very system that cages them. Clever, isn’t it?

SOCIAL DIVIDE AND DISENFRANCHISEMENT, Carpenter underscores the exploitation of the population through Nada and Frank, characters who are barely scraping by in a world where their hardships are invisible to the affluent. Nada’s frustration with his lack of opportunity reflects the frustration of a disenfranchised middle class in the 1980s, though this divide continues into today.

“They Live” presents a brutal, unfiltered look at social disenfranchisement, driving home the sharp, biting reality that those at the top keep the rest conveniently invisible. Nada, with his raw frustration, embodies the population forced into survival mode while the elite revel in gleaming towers of luxury, blind to the suffering at their doorsteps.

The film’s sharp, dystopian contrast between the affluent zones and urban decay is more than mere set design; it’s a fierce visual indictment of systemic marginalization, unemployment, and economic looting. reflecting the unbridgeable chasm between those who have and those who never will. Unemployed, littered streets, and dilapidated neighborhoods aren’t just backdrops, they’re Carpenter’s hauntingly prophetic visual for the marginalized spaces where people are consigned to linger, hopelessly forgotten by the sanitized, comfortable upper echelons. It’s disturbingly prescient. “They Live” doesn’t just reflect the 1980s, it serves as a prescient critique of a world where the wealthy insulate themselves further with each passing year, a world where the glistening promise of prosperity turns out to be a cruel façade for most.

Carpenter’s world, as in ours, the population is seen as expendable, dispensable, and if they’re fortunate enough, invisible. The “Sleepers” and Willful Ignorance Even with glasses that reveal the truth, many in the film choose not to see the reality, a nod to people who turn a blind eye to inequality, injustice, and manipulation in exchange for comfort. This notion of “sleepers” is critical: Carpenter suggests that people can be complicit in their own oppression if it means they can keep their comfortable illusions intact.

The question is, do we want to see the truth, or would we rather stay in the bubble? The cozy allure of denial, it’s such a darling trap, isn’t it? Carpenter’s “sleepers” in “They Live” are an unsettling reminder of a truth that cuts deep, sometimes, people are more than happy to sacrifice reality for a sense of comfort and stability. He’s not just calling out the usual villains of society, he’s pointing a polished finger at everyone who makes peace with the lie because it keeps them feeling safe. Now, that’s the rub, isn’t it? Seeing the world as it truly is can shatter one’s sense of self, dignity, and perhaps even sanity. Not everyone has the mettle to peer into the abyss and realize that the safety they treasure is built on exploitation, manipulation, and suppression.

Perverse irony, while some clamor for freedom, they might turn their backs on it if it requires abandoning their illusions. So, the choice, as Carpenter presents it, is stark and unyielding. To wield those lenses and face the visceral horror of truth, or to keep them off and savor the tranquil lie. Seeing demands responsibility, even rebellion. Staying ignorant, though? It’s so easy, so undisturbed. And therein lies the danger, it’s the sleepers that prop up the very systems that enslave them.

THAT LEGENDARY FIGHT SCENE, Yes, I have to bring it up. The infamous six-minute brawl between Nada and Frank over a pair of sunglasses, it’s not just two guys going WWE in an alleyway. This scene captures the intense struggle to wake up, to see the world as it truly is. Frank resists not because he doesn’t trust Nada, but because he fears the painful clarity that comes with seeing reality.

It’s a satirical masterpiece of choreography and desperation. That glorious six-minute symphony of sweat, stubbornness, and suppressed screams, Nada versus Frank, toe-to-toe in “They Live’s” unforgettable street brawl. Yes, it’s a brutal tug-of-war over a pair of sunglasses, but so much more than that. Those shades? A ticket to consciousness, a heavy-handed but brilliant metaphor for that often-unwelcome clarity.

Frank’s resistance isn’t just about avoiding a black eye, it’s about clinging to the sweet slumber of ignorance, because once those glasses slip on, there’s no going back. In this brawl, it’s less a clash of fists and more a clash of worldviews: Nada’s desperation to free Frank from his blind allegiance to a system that enslaves him versus Frank’s own deep-seated fear of facing the brutal truth lurking underneath his comfortable oblivion. They drag it out, both literally and figuratively, because this is the kind of clarity that hurts. It’s not just a fight, it’s a savage parody of the lengths we’ll go to avoid seeing the world as it is. An absurd, drawn-out wrestling match to represent every bit of resistance we throw at the truth when it finally grabs us by the collar.

Final Thoughts

“They Live” is unapologetic, brash, and angry, using the campy trappings of a sci-fi action flick to deliver a message that still resonates today. Carpenter’s distrust of unchecked corruption, exploitation, and media manipulation have only grown sharper as society has evolved (or devolved). The film’s simplicity in terms of good versus evil doesn’t make it any less effective, in fact, its punchiness hammers the message home even harder. And in Nada’s final act of rebellion, he exposes the elites in a daring, death-defying move that reminds us that resistance is always an option, no matter how deeply ingrained the structures of power might seem. Carpenter’s film asks a question that we’re still grappling with: Are we too comfortable being “asleep” to change the status quo.

“They Live” is more than a sci-fi, it’s a fiercely defiant reminder that sometimes, the only antidote to a hypnotized society is to shove the truth in its face, even if it takes a pair of magic sunglasses to do it. Carpenter didn’t just slap a dystopian gloss on consumerism and call it a day; he took a sledgehammer to our cozy illusions of autonomy, one swinging punch at a time. Nada’s ultimate act of rebellion doesn’t feel like a scripted finale, but like a scream ripped from Carpenter’s soul, raw, reckless, and unforgiving. The brilliance here is how unapologetically ugly the fight against power is portrayed; there’s no neatly wrapped heroism or soft-spoken revolution.

Nada’s “last stand” is an explosive reminder that resistance is messy, dangerous, and often met with brutal, unforgiving force. The “sleepwalkers” Carpenter highlights are a biting reflection of the collective apathy we’re haunted by today. Are we awake, or do we just prefer the comfort of sleep? That’s the real horror beneath the camp and the quips. So, the choice is ours: do we reach for those sunglasses and confront the grotesque mechanisms pulling our strings? Or do we keep living in oblivion, complicit in our own deception? “They Live” doesn’t wait for you to decide, it dares you to look away.