For most of us, the words “Snow White” conjure up happy images of childhood. We remember watching the beloved 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, or being read a bedtime story from Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics. Most people leave fairy tales behind once they reach the age of ten, but clearly I never did (you’re about to read 3,000 words on the topic). That’s because they are actually so much more interesting than most people imagine. You’d never know from an initial casual read that the Snow White tale and its themes are intertwined with topics ranging from infertility to religion, or that the story often explores cannibalism, immortality, and primal fears. Today I want to introduce you to a completely different version of the children’s tale; the darker, more complex version that lurks beneath the shiny Disney-fied surface. Like many stories such as these, it starts with a maiden and a witch.

The Maiden and The Witch

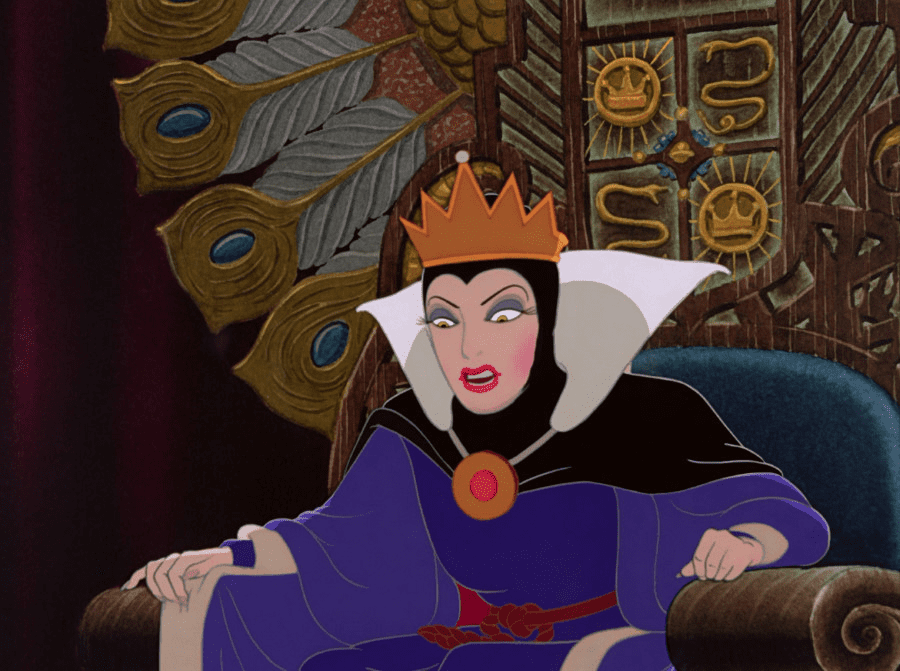

I like to think of Snow White and the evil Queen as two sides of the same coin, or two women on either side of a mirror. On one side we have Snow White, the beautiful heroine, nearly perfect in both appearance and soul. She sings, she dances, she cooks for the seven dwarves, she doesn’t attempt to kill the queen when the queen has her hunted down in the forest. She is an exquisitely saccharine image. On the other side of the mirror we have a terrifying portrait of jealousy and rage. The queen has wealth and power but is overflowing with dissatisfaction. She has a murderous heart and a propensity for cannibalism (in some tales, at least). The two seem to have nothing in common, and yet I would say they are working towards the singular purpose of the authors of these tales. The Snow White tale, in my opinion, is a commentary on beauty, and both attempted murderess and victim are playing a role to the same end.

The Maiden Archetype

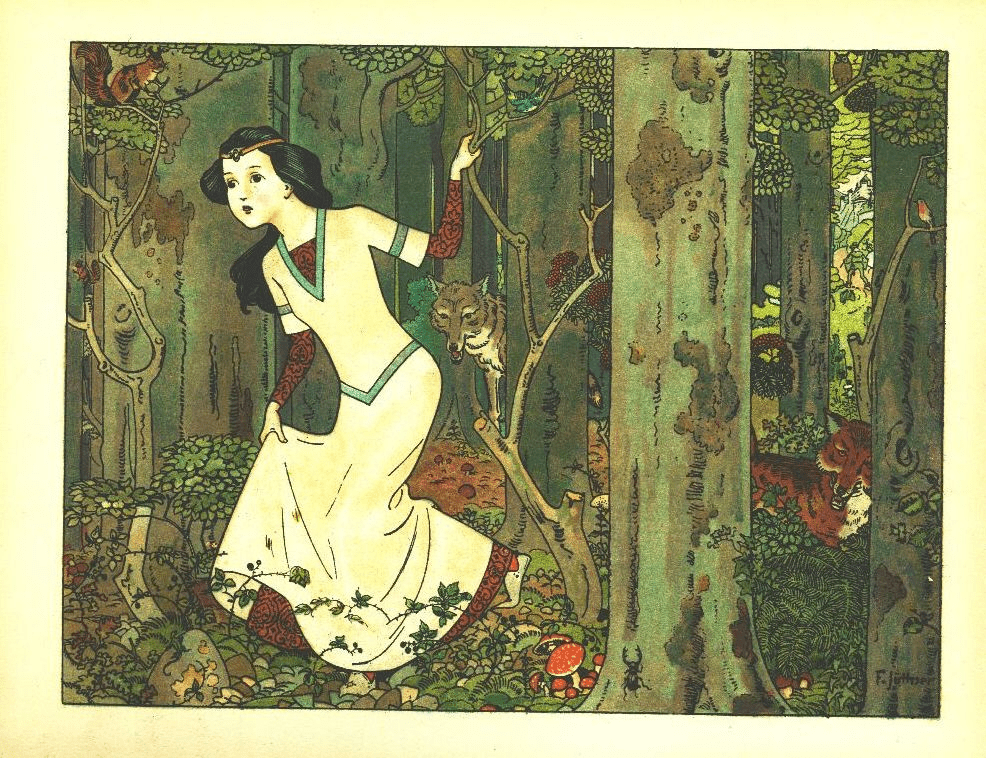

The “damsel archetype” or “maiden archetype” is so broad and commonly used that you could put thousands of characters into the category without trying. Nearly all Disney princesses, and most female fairy tale protagonists, fall into this box. The maiden is simple: she is innocent, she is beautiful, and she possesses a kind of golden goodness that can only be found in the young. Snow White is a nearly perfect example of a maiden. She is young and attractive, with abundant descriptions of her flawless skin and ebony hair and red lips in the Grimm version. Her beauty is such that it is mentioned in the titles of some variations, such as the Spanish “Beautiful Stepdaughter,” and Swedish “Daughter of the Sun.” Her goodness and innocence is also made obvious, especially compared with the repeated murder attempts of her rival. Her only fault is her easily forgivable naivete when she accepts a poisoned garment, comb, or apple. It is easy to look at these traits separately and leave Snow White as a simple children’s story about the perfect protagonist versus the evil queen, but things are rarely so straightforward.

The first step towards understanding the tale is realizing that Snow White’s beauty and goodness are inextricably linked. Beauty and morality have been connected since ancient times up until today, and this often presents itself in stories. Around the time period that the Grimm brothers wrote “Sneewittchen,” later translated into the Snow White version we all know, beauty was essential to being considered sociable and polite. Rough skin from hard labor as well as disease and disfigurement were common in the 18th century, which made “a pale, smooth complexion…a sign of social status.” (Norfolk). Although back then the link between beauty and goodness was more observation than statistical fact, we now have studies on our side to show it is true. Recent research shows that we are 20% more likely to consider a beautiful person warm, sincere, and generous based on looks alone (Hendricks). This connection between morality and appearance affects women, and subsequently female characters, in specific ways. According to some studies, women are often reduced to their bodies/appearance alone when being viewed by others. Sandra Bartky brings up the idea of women being “represented” by their bodies, or “identified” solely by their bodies. In my opinion, Snow White’s beauty was written into the story very purposefully. Her perfect, pale complexion and shiny black hair “identify” her as good; her youth and attractiveness are part of what marks her as innocent. Snow White tales, at their core, are not so much about goodness, but are mores of a commentary on what happens to women as they age. Snow White is one side of the coin; she represents youth, beauty, and the inherent innocence that we believe lies beneath. It’s time to take a look at the other side.

The Hag/Witch Archetype

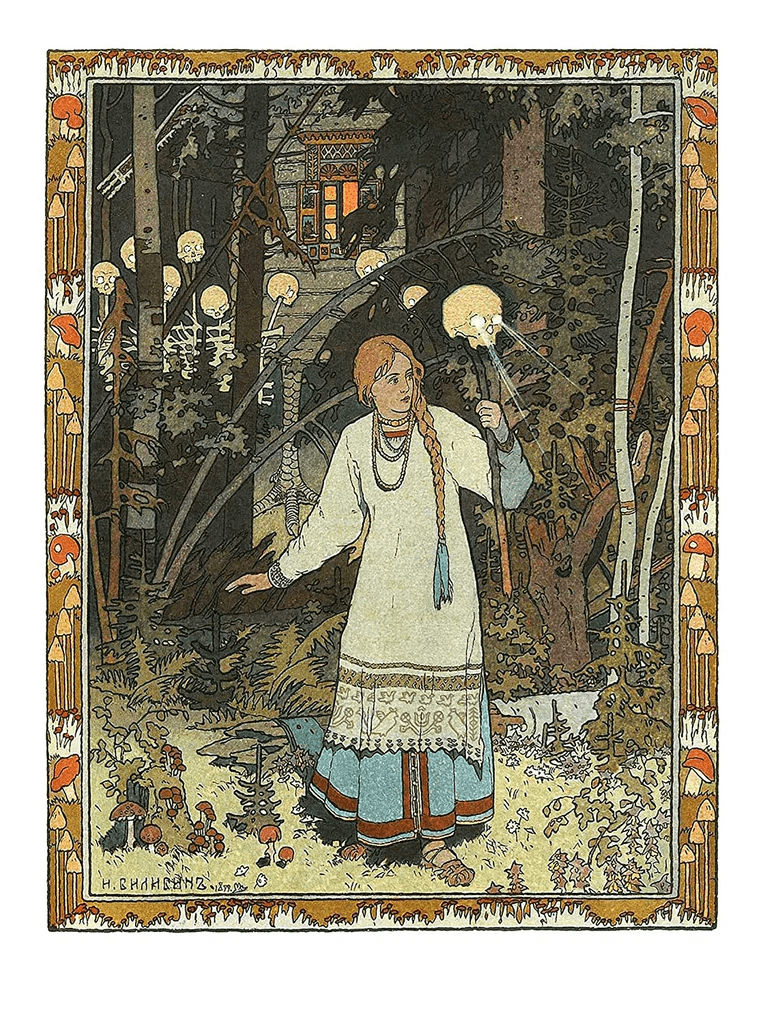

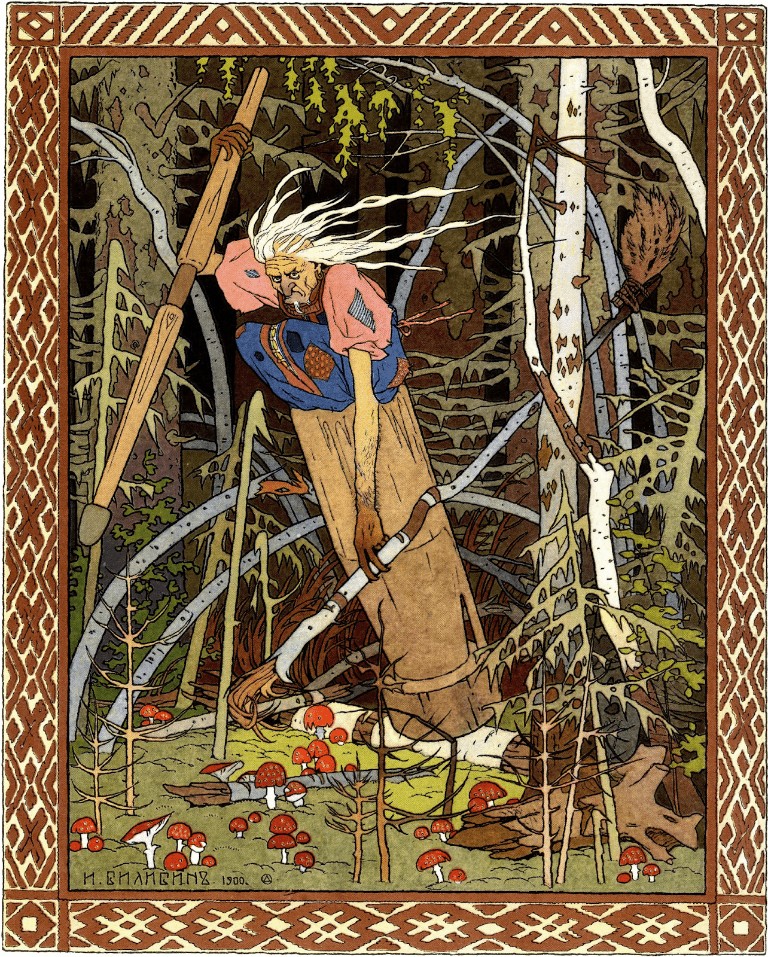

Older and aging women aren’t treated nicely in folklore. They have webbed feet, odd teeth, hunchbacks, or a cackle. Sometimes they grant wishes or take in travelers, but most of the time they predict death, cause death themselves, or steal children in the night. The saddest thing about the queen/mother figure in Snow White tales is that she is rarely described as having grotesque features. She is no hunchbacked, web-footed creature; she is just an older woman. Sometimes, specifically in the Grimm version, she is portrayed as beautiful, simply coming in second to Snow White. Unfortunately, this is enough. The queen is now the “uglier” character in the story, and her appearance is tied to her morality as much as Snow White’s is. As soon as she looks into the mirror and finds herself lacking, she is no different or less dangerous than any other night hag. In addition to sharing an aging look with other old woman folklore creatures, she also shares an inclination to use magic. In the popular Grimm tale, the queen character’s practice of witchcraft is part of her evil persona. The antagonist practices magic in many other tale variations as well, sometimes by sending fairies to kill her, enchanting a rock to swallow her up, or turning her daughter into a bird (somehow this happens in multiple variations). Older women practicing magic is heavily linked with evil in most versions of the tale even if the antagonist doesn’t do the magic herself. In “the Good Daughter,” for example, a witch sent by Snow White’s mother attempts to deceive her with an enchanted ring. In my opinion, when magic exists in stories it often points to a fear of the unknown, or an attempt to explain the unexplainable. There was likely something mysterious and mystical about older women that authors didn’t understand when writing folklore. Magic gives shape to this lack of understanding; it brings to light the fear the writers had of aging and the uncertainties that come with it. As decades passed, that fear did not dissipate. Possessed or evil older women remain common main and side characters in horror movies (think The Taking of Deborah Logan, Pearl, or The Shining).

I always found it interesting that in the 1937 Disney version of Snow White the queen is beautiful, but very heavily made-up, with shining lips and highly arched brows. I think this portrayal shows the battle aging women have with beauty; there is simply no treatment or product that will turn the clock back ten years. Youth and “natural” beauty, whatever that means in the moment, has always held an incredible amount of value. We can see the effects of that value in the lengths women of the past and present go to create and preserve beauty. An ancient Egyptian woman would spend hours taking milk baths, applying face masks and makeup, and even removing hair through a process called “sugaring.” Similarly, the average modern woman may spend up to 55 minutes per day on beauty prep, and her routine involves up to 16 products (Elsesser). Despite the clear differences in the appearances of Snow White’s evil queen and grotesque folklore or horror movie characters, there is no difference in the levels of internal evil. That is because, in my opinion, a woman doesn’t need to be disgusting to be seen as immoral by society, she needs to be merely “past her prime.”

Motherhood Is All The Rage

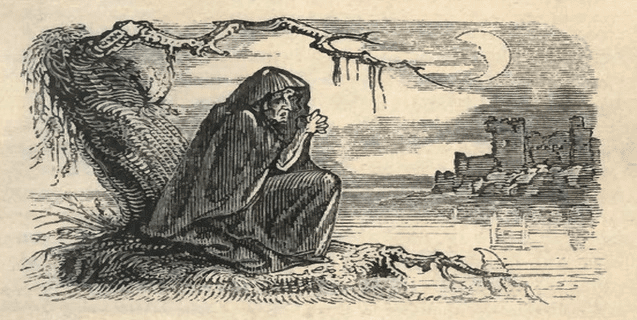

For a young girl, the mother figure can bring infinite comfort and protection, but can also be a source of pain and despair. For a mother, her daughter can bring feelings of pride and love, or alternatively, jealousy and rage. As the many mothers of the many Snow White variations attempt to poison, maim, and hunt down their daughters, we come to realize as readers that monstrous maternity is an important theme. Fear of mothers is not a new concept in folklore. In fact, some of the most notorious creatures in folktales are the vengeful ghosts of mothers. The Pontianak, a Malaysian folklore character, is said to be the spirit of a woman who died in childbirth. Unlike many ghosts that can only spook humanity, she has the power to kill, ripping into the abdomens of her victims with long fingernails. The Rusalka, a slavic folklore creature, lurks in waterways like a frightening mermaid. In some tales, she is the spirit of a woman violently drowned after becoming pregnant. The bean-nighe, a Scottish folklore character, is sometimes thought to be the spirit of a woman who died unexpectedly giving birth. She will continue washing the clothes of the dead until the day she should have originally died herself. In modern times, we often associate the mother figure with warmth and positivity, but folklore has always tapped into the unsightly underbelly of motherhood.

Youth, Beauty, & Envy

One “unsightly” emotion that can arise in motherhood is envy, and Snow White stories are absolutely rife with it. Envy is the villain’s main motive, after all. But where do these feelings come from? In some versions the envy clearly comes from outside sources. “La Bella Venezia” shows the stepmother asking various townspeople their opinions on her beauty versus her stepdaughter’s beauty and gets answers she does not like. In “Lasair Gheug” and “Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree” the mother is warned of her inferiority via a talking fish. However, in other variations such as the popular Disney version, the villain sits before a mirror and her envy is born from her own insecurities. Or so the Snow White stories would have us believe. Most of us are aware, on some level, that our insecurities are not entirely made up in our minds but are rather a reflection of the complex web of expectations and standards around us–standards that we rarely meet. The mothers of Snow White are painted as simple and vain villains, but for mothers in reality, envy of daughters likely stems from societal fixations on beauty and youth.

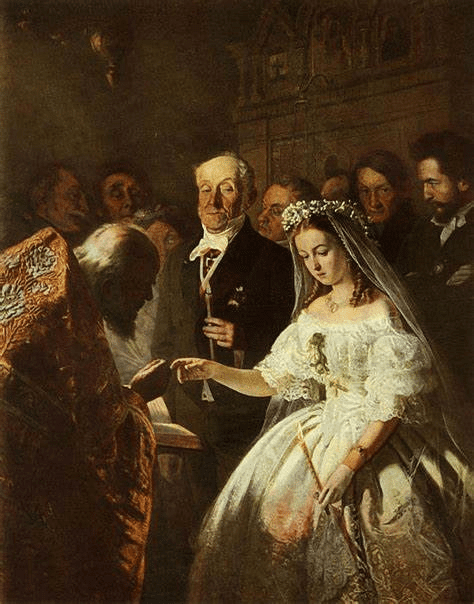

As early as medieval times, beauty (specifically natural beauty) was connected with morality, and so it was quite important to be beautiful. Youth was also important, as shown by the difference in marriageable age. The age girls could get married in medieval times was several years younger than the age boys could get married (Davidson). Marriages between teen brides and grooms in their twenties or thirties were common among the elite (Brooke). In the modern world, we now have studies to show us that men prefer younger women (Antfolk), and that beauty is somehow still linked with morality, as I’ve already discussed. These fixations on beauty lead to objectification. According to research: “both men and women perceive sexualized women as lacking in certain human qualities such as mental capacity and moral status” (Kellie). Unfortunately, when a woman is objectified by those around her, she begins to objectify herself. If the mothers of Snow White were to live in reality, they would be participating in self-objectification when they gazed into their magic mirrors, telling themselves that they are not good enough. And apparently, self-objectification is enough to drive anyone a little crazy. According to a 2017 study, “self-objectification has been associated with increased opportunities for…body shame, appearance anxiety, disrupted flow, and reduced sensitivity to internal bodily cues…which consequently predict more symptoms of depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders.” (Calogero). Unfortunately, the authors of the Snow White tales overlook the complicated relationship that women, particularly mothers, have with beauty and aging. Instead the authors write the same cartoonishly evil and unattractive character each time without fail. The Snow White tales are decades old and written mostly for children so we can’t expect much nuance, but if done better the story could provide an interesting insight into what societal standards can do to mothers with daughters.

Power Over Life and Death

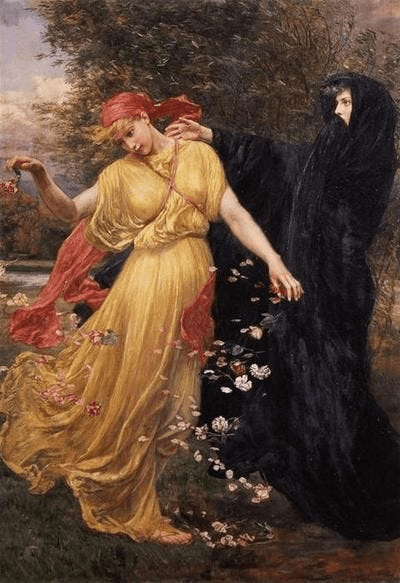

The mothers of Snow White were trying to do more than express rage and envy when they hunted down their daughters. In my opinion they had a far more impressive motive: they desired power over life and death. Or rather, they desired to have it back. In myths and folktales, female characters often preside over both birth and death. As far as birth goes, obviously women give birth themselves, but there are also many goddesses of fertility (Hera, Demeter, Isis, Aphrodite, Ishtar, etc.), and female folklore spirits who were mothers or soon-to-be mothers before their untimely demise (Pontianak, Rusalka, Bean-Nighe). Alongside these birth goddesses/spirits are the goddesses and spirits of death and the underworld, such as Persephone, Hecate, Morrigan, Lilith, Medusa, and Hel. Often there is overlap; the Bean-Nighe, for example, can be spirits of mothers, yet they are messengers of death.

Unfortunately, when you aren’t a goddess or otherwise mythical woman, you lose your power over birth/life as you age. Snow White tales often bludgeon me with the yearning and regret of the mother character. She feels powerless, hopeless, as if she has lost something. These feelings blossom grotesquely into violence. Sometimes just murder, other times cannibalism. Yes, you read that correctly. Walt Disney would never. And yet, so many European variations of the tales did. In the Scottish tale “Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree,” Silver-Tree wishes to consume the heart and liver of her daughter. In “The Daughter of the Sun and the Twelve Bewitched Princes,” the mother actually does eat what she assumes to be her daughter in the form of a bird. In Grimm’s “Sneewittchen,” the mother actually mentions immortality as a reason for wishing to consume her daughter’s heart. In many other tales the mother does not actually eat her child, but does desire “tokens” such as a vial of her blood or her tongue. These cannibalism mentions in Snow White tales interest me because they are literal attempts by the mother character to absorb her daughter. Absorb her for what purpose? To put her back into the womb? Is the desire to eat her child caused by parental regret? This is one interpretation. The interpretation that I like to indulge in, however, is the idea that the mother wishes to absorb her daughter’s power; to regain the power she once had over life through death. As I’ve said before, youth is, and has been, incredibly valued in women. It is linked with morality, with beauty, and with the ability to give birth, yet another highly valued female trait. Many malicious folklore creatures are the spirits of barren women or women with stillborn children. Infertility is a centuries old, deeply ingrained fear that is linked to the perceived loss of power that comes with aging. Both the real world and stories often beg the question: if a woman is old, ugly, and infertile, what is the point of her existence? The mothers of the Snow White tales also ask themselves this, and then decide to kill and consume to get their currency back. While a murder scene is awful to read through, the motive behind the vile actions is enlightening, even decades after the tale was written.

Where Is God In All This?

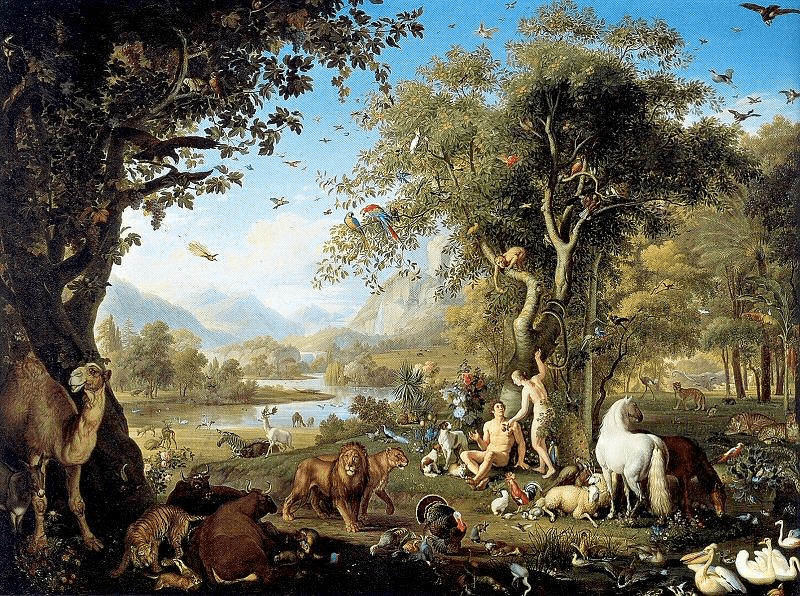

Everywhere, actually. Although we could probably draw connections between Christianity Judaism with other fairy tales, Snow White is perhaps the most on the nose. If the heroine wasn’t supposed to represent Eve in some way she wouldn’t have been tempted by an apple in Grimm’s and Disney’s variations. Snow White isn’t just similar to Eve in her desire for an apple, however. She is also, as her name suggests, as pure and innocent as freshly fallen snow. Her personality is a perfect mirror to Eve’s childlike naivete before her fall from grace. Just like Eve, Snow White’s story is one of temptation. Although she may not be as vain and envious as her mother/stepmother, she is not entirely immune to feelings of inadequacy. Every woman, no matter how young and beautiful in the moment, must age. Additionally, no woman can be quite beautiful enough. There are no limits to something as intangible as beauty. This is why, although the most well known versions of Snow White involve the biblical apple, many versions replace the apple with a bodice, dress, stockings, comb, or other beauty enhancers. Whoever offers Snow White the tempting object, whether it is her mother in disguise or a witch or servant sent by the mother, represents the snake. The role of the snake in Eve’s story is to offer her something she feels she is missing, and the witch in Snow White is no different. Despite her youth and superiority to her mother, Snow White still feels insufficient, and the mother/witch preys upon those insecurities. How poetic for the daughter of a woman driven insane from her own vanity to die by poisoned comb.

If Snow White represents Eve, what do the villian(s) of this tale represent? The mother/stepmother is likely a representation of Lilith or Satan, and sometimes the snake, as she occasionally disguises herself in order to tempt Snow White into sin. The stepmother’s mirror is at times a villain in its own right. For example, in “the Beautiful Stepdaughter” a literal demon sows the seeds of envy in the antagonist. In many Italian versions of Snow White the seven dwarves are instead robbers, which suggests they too may be a form of “bad guy.” I think that, in many variations, the dwarves/robbers are a part of Snow White’s failure to save herself. God alone being able to save you is a big idea in some sects of Christianity. If these tales have ties with Christianity, it makes sense that the Snow White’s meager attempts to escape evil go awry. Instead of preserving her inherent goodness, she shacks up with robbers (the horror!) and gives in easily when a pretty dress or stockings or sugared almonds are waved in front of her. Thankfully she doesn’t allow her faults to lead her down the path of murder, and so she escapes the brutal death that her mother often faces.

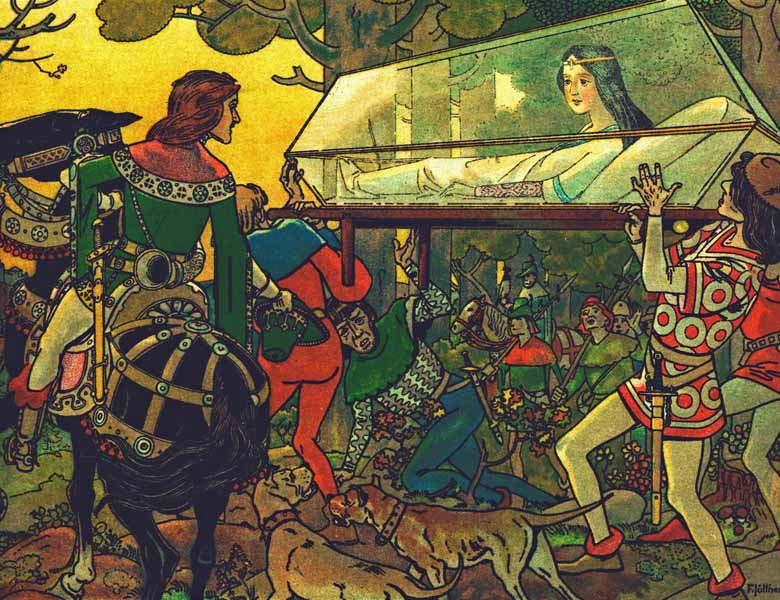

If Snow White represents Eve and her mother is Lilith/Satan, then her savior must represent God. Typically Snow White is saved by a handsome prince who falls in love with her, but sometimes, such as in “Sneeuwwitje,” her savior is her father. This lends rather nicely to the notion that her savior is the God-like figure (angel, divine hero) in the story. When thinking about this story in terms of religious connections, I find it interesting how Snow White tales treat death. In most versions it appears as a temporary state; something that one can be woken up from. This correlates with the Christian idea that death is not actually the end for the faithful. Instead believers will be woken up/saved by God after they die and will live their own version of happily ever after in heaven. Meanwhile non-believers or evil-doers such as Snow White’s stepmother will experience eternal death and suffering.

Although it creates interesting religious connections and delves into the desire for immortality, the Snow White tale remains frustratingly surface level and problematic in other areas. Despite being interesting conceptually, both the heroine and villain are, at their core, shallow caricatures of the damsel and the witch. The story fails to understand the complexity of a woman’s relationship with beauty and perpetuates the centuries old fear of infertility. Despite recognizing why a mother might want to steal her daughter’s youth, the story continues to demonize aging overall. The story’s uncomplicated morals (“don’t be vain or envious!” and “if you behave well, you’ll achieve happily ever after!”) are suitable for Christian children, but with a more mature eye we can start to look beyond the simple exterior and try to understand the prejudices that drive the story. Ultimately, this is why folk and fairy tales are important. We are analyzing very old stories, and in doing so we can catch a glimpse of how far back harmful ideas go. Current views can be traced back to a disappointing foundation, and as we read we are able to see just how large that foundation is. In the case of Snow White, it is clear that certain ideas were shared across most of Europe, from Germany to Italy to the Netherlands. Treating folklore as the serious piece of history that it is allows us to build maps of injustice that may give us insight into why things are the way they are, and what we should change.

REFERENCES

Antfolk, Jan. “Age Limits.” Age Limits – PMC (nih.gov)

Brooke, Christopher. “Betrothal: Marriage Age.” Betrothal: Marriage Age | Encyclopedia.com

Calogero, Rachel, et. al. “Trappings of Femininity: A Test of the “Beauty as Currency” Hypothesis in Shaping College Women’s Gender Activism.” Trappings of femininity: A test of the “beauty as currency” hypothesis in shaping college women’s gender activism – ScienceDirect

Calvino, Italo. Italian Folktales. Pantheon Books, 1980.

Davidson, Lucy. “Love, Sex and Marriage in Medieval Times.” Love, Sex and Marriage in Medieval Times | History Hit

Elsesser, Kim. “The Link Between Beauty and the Gender Gap.” The Link Between Beauty And The Gender Gap (forbes.com)

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Bantam, 1987.

Heiner, Heidi Anne. Sleeping Beauties: Sleeping Beauty and Snow White Tales from Around the World. SurLaLune Press, 2010.

Hendricks, Scotty. “Beauty Bias: We Tend to Think Pretty People are Morally Superior.” Beauty bias: We tend to think pretty people are morally superior – Big Think

Kellie, Dax. “What Drives Female Objectification? An Investigation of Appearance-Based Interpersonal Perceptions and the Objectification of Women.”

Norfolk Towne Assembly. “‘Standards of Beauty’ in 18th and Early 19th Century England and America.” “Standards of Beauty” in 18th and Early 19th Century England and America (norfolktowneassembly.org)

Papadaki, Evangelina. “Feminist Perspectives on Objectification.”

Feminist Perspectives on Objectification (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Directed by David Hand, Walt Disney Productions.

SurLaLune. “Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree (A Celtic Tale).” SurLaLune Fairy Tales: Tales Similar To Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (archive.org)